1 Introduction

A leading authority on mental health in children in the UK has estimated that, in the average secondary school of around a thousand pupils at any one time there will be fifty students who are clinically depressed, a further hundred with significant emotional difficulties, ten affected by eating disorders and up to ten who will attempt suicide in the next year (Mind, 1997). The importance of mental health in children and young people is highlighted by recent concern about increases in:

- children with disruptive behaviour being excluded from schools;

- violence in schools and juvenile crime;

- psychosocial disorders in young people;

- suicides and incidences of self-harm among children and adolescents;

- the numbers of children affected by marital breakdown;

- the numbers of children involved in substance abuse;

- the incidence of children subjected to abuse or neglect.

Despite these factors, children’s mental health has so far been paid insufficient attention in schools. Teachers are uniquely placed to influence the mental health of children and young people. As well as being in a position to recognise the symptoms of mental health difficulties at an early stage, they can enhance the social and emotional development of children and foster their mental well-being through their daily responses to pupils. According to the Mental Health Foundation (1999), schools have ‘a critical role to play’ in these aspects of mental health. In addition, Rutter (1991) provides evidence that school experiences are important for children’s psychological, as well as their intellectual, development and asserts therefore that schools need to concern themselves with children’s self-esteem and their social experiences, as well as their academic performance. So, to suggest that schools need to focus on mental health issues ‘is not simply to add yet another demand to a teacher’s already impossible workload; effective social and affective education is directly beneficial to academic attainment and can therefore help teachers be more effective’ (Weare, 2000: 6).

The majority of children with mental health problems never reach specialist services so their needs have to be addressed by mainstream institutions, such as schools. At the same time, current pressures on schools, such as the demands of the National Curriculum, make it more difficult for teachers to address the emotional and social needs of pupils. Whilst it is desirable that children achieve academic success, personal and social development are also vital if they are to grow into well-adjusted adults. The inclusion of children with a wide range of special needs in mainstream schools means that today’s teachers must also support many troublesome and troubled children, whose needs are not easily met. Although some teachers may consider that meeting the mental health needs of children does not fall within their remit, unmet emotional needs inevitably impact on children’s learning and make the task of teaching more difficult. So it is therefore important for teachers to directly address children’s mental health needs.

Many mainstream teachers lack awareness of children’s mental health issues. They lack the necessary knowledge, understanding and skills for addressing the needs of children with mental health problems. At times, even very experienced teachers can feel out of their depth when faced with such pupils. They may be uncertain about the approach they should adopt or have concerns that whatever they do may exacerbate these children’s difficulties. This dilemma is sometimes reinforced by the reluctance of health professionals to share information with teachers and their failure to acknowledge the constraints that teachers are under when working with these children in a mainstream school setting. It is important that teachers have more knowledge and understanding of children’s mental health problems and that they are aware of potential strategies for addressing them. With increased knowledge, training and experience, teachers can do a lot more to improve children’s mental health.

This handbook spans the boundary between mental health and education. In doing so, it is hoped that it will provide the information and guidance teachers need to help pupils with mental health problems. They must also be able to recognise, however, the limits of what they can achieve alone, as well as the indications that children should be referred for more specialist help. When working with pupils with diagnosed mental health disorders, a teacher’s role should be complementary to that of mental health workers, with whom they will need to liaise closely.

Definitions

Most teachers will be aware of pupils with emotional and behavioural difficulties (EBD), but there is often considerable uncertainty about the boundaries between ‘normal’ misbehaviour, emotional and behavioural difficulties, and mental illness. Within DFE Circular Number 9/94 (DFE, 1994a: 4) children with EBD are described as being on a continuum, with their difficulties lying between ‘occasional bouts of naughtiness’ at one end and ‘mental illness’ at the other. When assessing children, whether they have EBD will depend on ‘the nature, frequency, persistence, severity, abnormality or cumulative effect of the behaviour’ compared with normal expectations for children of their age. EBD can take a wide variety of forms. The Special Educational Needs Code of Practice (DFE, 1994b) refers to withdrawn, depressive or suicidal attitudes, obsessional preoccupation with eating habits, school phobia, substance misuse, disruptive, antisocial and uncooperative behaviour, as well as frustration, anger and threats of violence.

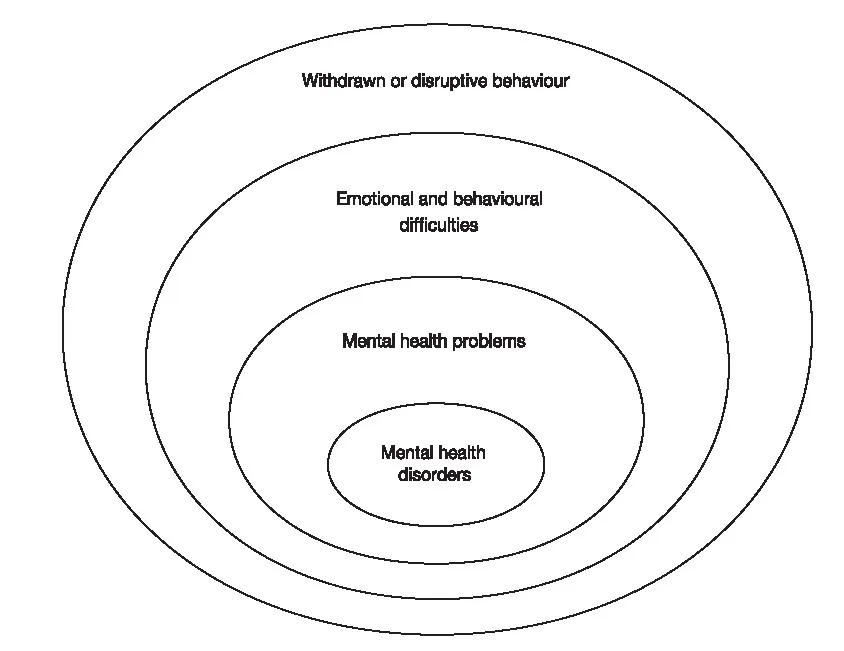

Teachers, however, are rarely able to articulate a clear definition of EBD (Daniels et al., 1999). Hyperactive children, for example, are frequently described as naughty. Teachers may find it difficult to assess where on the continuum between ‘occasional bouts of naughtiness’ and ‘mental illness’ children lie. They need, however, to be able to distinguish between them in order to be able to take appropriate action. The relationship between EBD, mental health problems and mental health disorders can be conceptualised as on a continuum (Weare, 2000), as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The relationship between EBD and mental health disorders

Many children exhibit occasional episodes of disruptive or withdrawn behaviour, but for some children these episodes will be severe enough and persistent enough to be considered as evidence of EBD. The difficulties of a proportion of the children with EBD will also be sufficiently severe to constitute a mental health problem, for example children who are diagnosed as clinically depressed. Similarly, some of these children’s difficulties will be considered so extreme that they warrant classification as a mental health disorder, such as schizophrenia. Therefore, whilst EBD affect a relatively large number of pupils, mental health disorders affect a relatively small, but still a significant, number of children. One would also expect to find a far higher degree of mental health problems within a group of children already identified as having EBD than in a randomly selected group of children, which is in fact the case. Mental health problems and EBD also share common risk factors, which are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

A mental health problem is defined as ‘a disturbance of function in one area of relationships, mood, behaviour or development of sufficient severity to require professional intervention’ (Wallace et al., cited in the Department of Health, 1995: 10). A mental health disorder is defined as ‘a severe problem (commonly persistent), or the co-occurrence of a number of problems, usually in the presence of several risk factors’ (ibid., 1995: 10). The Department of Health (1995) stated that the significance of a mental health problem could be determined by:

- its severity

- its complexity

- its persistence

- the risk of secondary handicap

- the child’s stage of development

- the presence or absence of protective and risk factors

- the presence or absence of stressful social and cultural factors.

An understanding of the distinction between occasional withdrawn or disruptive behaviour on the one hand and EBD, mental health problems and disorders on the other is a crucial one. The severity and persistence of the problem need to be taken into account otherwise inappropriate responses may be adopted. A child who is persistently withdrawn following bereavement and has difficulty concentrating on his or her schoolwork, for example, may be perceived as lazy, or a child with a conduct disorder may be rejected because of his or her disruptive behaviour. As a result, vulnerable children may be further alienated from those who could provide them with the understanding and support that they need to help alleviate their problems. Educational policies that focus mainly on children defined as having EBD may result in children who have more internalising disorders, such as depression and anxiety, being neglected (Mental Health Foundation, 1999). This is because their difficulties are less obvious and cause teachers and other pupils fewer problems than children with externalising problems, such as behavioural difficulties.

The importance of children’s mental health

A high priority has recently been placed on addressing the mental health needs of children and adolescents (Department of Health, 1995) because:

- mental health difficulties cause distress and may impact on many or all aspects of children’s lives and, as well as affecting children’s emotional development, they may affect their physical and social development and their educational progress;

- children’s mental health difficulties have implications for all those involved in their care, as well as those who come into contact with them on a daily basis, such as teachers and other pupils;

- problems unresolved at this early stage can have long-term implications and may lead to a disrupted education, poor socialisation and a lack of mental well-being in adulthood;

- mental health problems in children increase demands on other services, such as social services, educational and juvenile justice services.

There is growing awareness of the impact of school experiences on children’s mental wellbeing. School years are a vital period in children’s lives, particularly for their emotional development, and a safe and secure environment is essential for them to grow up happy and confident. Teachers, among others, should encourage children to form healthy and effective relationships, help them to achieve their potential and should prepare them for increasing independence. Children can, however, experience a variety of pressures and difficulties during their school years. Some have difficulty coping with these challenges and this can have a serious effect on their lives in the future.

The prevalence of mental health problems

Mental health problems are relatively common in children and adolescents, although severe mental illness is rare. It has been suggested that 20 per cent of children display some sign of poor mental health and a proportion of these may require professional help for mental health problems at some time (Department of Health, 1995; Mental Health Foundation, 1999). The prevalence rates of specific disorders are discussed in more depth in individual chapters. There is good evidence to suggest that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents is similar in all developed countries. Within most ethnic minority groups in the UK the rates of psychiatric problems are generally similar to those of the general population, although the circumstances that lead to them may differ. In the African–Caribbean population, however, higher rates have been found.

The prevalence of mental health disorders varies with the type of problem and the age and sex of the child. The most common mental health disorders are conduct disorders and emotional disorders, which are found in about 10 per cent of 10-year-old children. Some problems, such as feeding and sleep difficulties, appear to be relatively common in young children, whilst others, such as bed wetting and temper tantrums, although still found in a significant proportion of children, appear to be relatively less common. Some problems, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder, eating disorders, suicide and attempted suicide and substance misuse, are particularly prevalent during adolescence, whilst others, such as soiling, become less common with increasing age. This highlights the relevance of a developmental approach to tackling mental health problems. Developmental issues are discussed in some depth in Chapter 2 of this handbook.

A Europe-wide increase in the incidence of a range of psychosocial disorders, including depression, suicide, delinquency, eating disorders, and drug and alcohol abuse, has been reported (Fombonne, 1998). Several studies also suggest an earlier age of onset for these disorders. This has implications for all professionals working directly with children and young people, especially teachers. Society is becoming more complex and families are less able to cope. Parents may be unavailable, whether through bereavement, divorce, illness or deprivation, to promote their children’s growth and development and this can have serious consequences. Children respond to these difficulties in various ways – they may become aggressive or withdrawn, they may feel anxious or afraid. These reactions can manifest themselves through sleep and eating problems, difficulties in learning, difficulties in forming relationships, depression or even attempted suicide.

Factors influencing the mental health of children

There is no easy way of telling whether children will develop mental health problems or not. Some children maintain good mental health despite traumatic experiences, whilst others develop mental health problems even though they live in a safe, secure and caring environment. There are, however, some common risk factors that increase the probability that children will develop mental health problems. These include individual factors, such as a difficult temperament, physical illness or learning disability, family factors, such as parental conflict and inconsistent discipline, and environmental factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantages or homelessness (Mental Health Foundation, 1999). Risk factors are cumulative. If children are exposed to one risk factor the likelihood of developing a mental health problem is between 1 and 2 per cent, but with four or more risk factors this increases to 20 per cent.

Stressful life events will affect some children more than others. An important key to promoting children’s mental health is a greater understanding of the protective factors that result in some children being more resilient than others. Factors that protect children against mental health problems also include individual factors, such as being more intelligent and having an easy temperament, family factors, such as good relationships with parents and an educationally supportive family, and environmental factors, such as a good support network and positive school experiences (Mental Health Foundation, 1999). The more protective factors the child experiences the greater the likelihood of mental wellbeing.

There is a complex interaction between the range of risk factors, their interaction with each other and with any protective factors, and this relationship is not clearly understood. However, children’s risk is greatly increased when adverse environmental circumstances, adverse family relationships and their personal characteristics reinforce each other. Research clearly suggests that as the disadvantages and the number of stressful circumstances accumulate, more protective factors are needed to compensate for this. Whilst biological factors may predispose children to some types of mental health difficulties, social circumstances, such as unemployment, divorce and stressful life events, and educational factors, such as their achievement and the school ...