![]()

Theories of Human Evolution | 1 |

Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.

Stephen Hawking (1942–2018)

Charles Darwin is now rightly recognised as one of the most important and influential scientists in history. However, in the middle of the nineteenth century, his radical theory of evolution, based on evidence he had gathered years before on his voyages on the Beagle to the Galapagos Islands, was something that he found extremely awkward to share with others and difficult to publish.

In Victorian England, the church had immense power and influence over people’s lives, and it took Darwin 20 years to pluck up the courage to publish The Origin of Species in 1859. He was a shy and humble person who was plagued by ill health and knew that his theories would be severely criticised by the church and the establishment. It was only because he was concerned that another young naturalist, Alfred Wallace might pre-empt his ideas that he finally agreed to publish. He realised that he was not a great speaker and was not well enough to expound his theories in person; instead, he relied on other naturalists, notably Joseph Hooker and Thomas Huxley, to champion his work.

In the introductory paragraph of The Origin of Species, Darwin hesitatingly writes: ‘until recently the great majority of naturalists believed that species were immutable productions and had been separately created. Some few naturalists, on the other hand, have believed that species undergo modification, and that the existing forms of life are the descendants by true generation of pre-existing forms’.1 It was only in the last chapter of his book that he makes any comment or reference about human evolution, with the immortal scientific phrase that light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.

The publication of Origin of Species was followed in 1871 with Darwin’s book The Descent of Man which expounded his theory of evolution of humans and apes from a common ancestor.2 There is little dispute today about the validity of this theory, although there is much argument about the manner in which the remarkable differences between the higher apes and humans were evolved (Figure 1.1). In Darwin’s time, however, there were only a few odd bones of a pre-historic Neanderthal man from Belgium, Germany and others from Gibraltar, and his concern was ‘whether man, like every other species, is descended from some pre-existing form’.2

FIGURE 1.1 Illustrated London News 1859. (Mr. Bergh was President of The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.) (Courtesy of Harper’s Weekly.)

More recently, Elaine Morgan writes: ‘Considering the very close genetic relationship that has been established by comparison of biochemical properties of blood proteins, DNA structure and immunological responses, the differences between a man and a chimpanzee are more astonishing than the resemblances’.3 These include structural differences in the skeleton, the muscles, the skin and the brain; differences in posture associated with a unique method of locomotion; differences in social organization; and finally the acquisition of speech and tool using, which together with the dramatic increase in intellectual ability, has led scientists to name their own species, Homo sapiens – wise man.

There is little doubt that the three main higher primate species – the gorilla, the chimpanzee and pre-hominid ape – evolved from the common ancestral African ape. But what were the circumstances which dictated such a divergent evolutionary path for hominins during which they acquired unique adaptations such as walking on two legs, a bigger brain, loss of body hair, subcutaneous fat, an excess of sweat and sebaceous glands, and changes in sexual and social habits? Hominins also demonstrated modifications to the upper airway and digestive tract, which were not seen in any of the other apes. We are no more special than any other species in evolutionary terms, although we have uniquely evolved the intellectual capacity to analyse our past history with the benefit of a modern understanding of evolution and genetics.

HUMANITY’S PLACE IN EVOLUTION

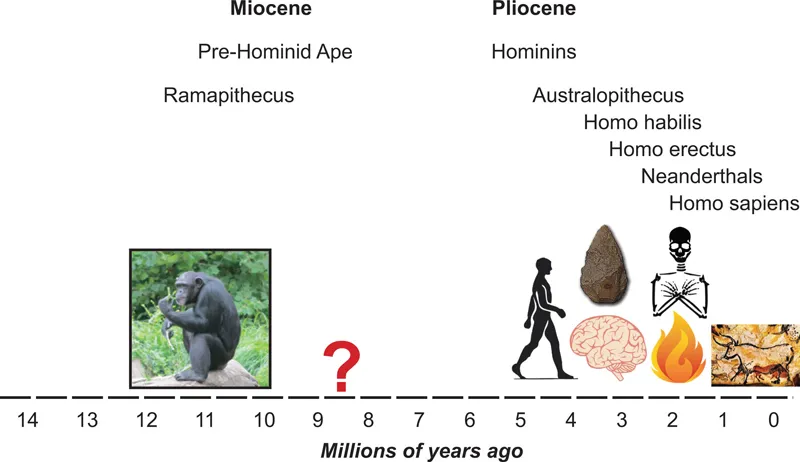

There are many gaps in the fossil record and our understanding of the evolutionary pathway of early humans (hominin species), but piecing the scant evidence together with the help of genetic analysis gives us a broad outline of how humans evolved from the first bipedal Australopithecines about 3–4 million years ago (Figure 1.2). There are several distinct milestones where new characteristics or features are apparent, either in the fossil record of ancestral hominin skulls or in early humans’ associated habitats or diet. There is also evidence of changes in their lifestyle and community interactions, quite apart from technical and intellectual advances. These important developments include bipedalism, use of tools, bigger brains, use of fire, ceremonial burials, and eventually the significant artistic and intellectual advances associated with the ‘cognitive’ revolution around 70,000 years ago.

FIGURE 1.2 The evolutionary ‘Black Hole’. (Courtesy of the author.)

It is difficult to explain many of these unique characteristics in terms of traditionally held beliefs of human evolution from the ‘Savannah Ape’, which assumes that ancestral hominin species evolved by changing from an arboreal habitat in the trees to a new lifestyle on the open grassland. Some other vital factor or circumstances must have played a role in motivating these unique adaptations, which are clearly more advantageous in setting humans totally apart from their primate cousins on a path of evolution leading ultimately to the emergence of Homo sapiens.

The crucial period of time during which these remarkable divergent evolutionary changes started to take place in the higher primates was in the late Miocene/early Pliocene epoch, which commenced about 9 million years ago and lasted roughly 5 million years. Fossil remains of ape-like pre-hominid primates during the preceding Miocene period are abundant both in Africa and Asia, and one bearing early changes in jaw structure thought to be possibly precedent to the hominin ape was Ramapithecus, discovered by G. E. Lewis in India in 1930 and later by Leakey in Africa. During this period, large populations of ape-like creatures flourished in temperate forest expanses widely distributed throughout Asia, Africa and Europe.

What happened next over the next few million years during the so-called evolutionary ‘Black Hole’ is uncertain, however, because there is little fossil evidence during this period. This may partly be explained by the fact that much of this period was during the Ice Ages and sea water levels were much lower because of the extensive frozen ice caps; indeed, many of the archaeological sites are now under water.

The iconic image of the quadruped monkey on the left with various images of ape/human-like creatures gradually becoming more upright and less hairy, leading to the recognizable human image on the right (Figure 1.3), is mere conjecture because we do not know precisely what and when these changes took place.

One of the main uncertainties in understanding evolution for much of the hundred years after Darwin was the important question about which came first, a bigger brain or bipedalism. Did our early ancestors acquire a larger brain and improved intelligence, which prompted them to think that standing upright would allow them to free their upper limbs and hands to be able to carry weapons and develop improved manual dexterity? Or did they acquire bipedalism out of survival necessity and then realise that they were able to use their hands and forelimbs for purposes other than quadruped locomotion?

Fossil evidence has shown that the majority of ape-like species, including the chimpanzee, gorilla, bonobo and orangutan, evolved with few changes during the Pliocene period and to the present time. However, remains discovered in the Olduvai Gorge in East Africa in the 1970s from about 3.5 million years ago indicate that a dramatic evolutionary step had occurred in one particular branch of the ape family. Australopithecus (‘southern ape’), as he was called, was different from all other apes in that he walked upright on two legs instead of four. His skull, however, was still the same size as that of a chimpanzee, confirming that bipedalism came well before a bigger brain.

FIGURE 1.3 Iconic Image of Ape/Man transition. (Courtesy of Science Photo Library/Science Source.)

The vital questions about bipedalism, brain evolution or any other aspect relating to differences between apes and humans were not really considered at the time of Darwin. Because the apes were tree dwellers and humans lived on terra firma, it was assumed that humans had simply dropped down from the trees onto the savannah and had stood upright because he ‘could see further’ and became a ‘hunter-gatherer’. In retrospect, this seems to have been a rather irrational assumption of post hoc ergo propter hoc (‘after this and therefore because of this’). Since there was little archaeological evidence to suggest otherwise and the mechanisms of evolutionary changes were poorly understood, there was never any consideration of an intermediate phase or other explanation for the significant differences that were to distinguish hominins from other primates.

Ever since then scientists have accepted the ‘savannah’ theory and have dismissed, criticized or ignored new ideas such as those proposed by Hardy4 and Morgan.3 There have been many excellent books on human evolution, but none of them have offered a plausible explanation for the unique characteristics seen in humans compared with other primates. It is largely thanks to Elaine Morgan, Professor Philip Tobias5 and Sir David Attenborough6 that the debate has been kept alive. Others, some looking from a medical rather than an archaeological perspective, have had the basic conviction that evolution may have followed a slightly different path from the savannah scenario.7,8,9,10

THE SAVANNAH THEORY

This traditionally held ‘savannah’ theory of evolution proposed in the nineteenth century and supported by Dart in 1924 has held sway for most of the twentieth century. This postulates that gradual evolution of ancestral humans from forest arboreal apes occurred because of climatic and behavioural changes. Loss of their forest habitat as a result of the late Miocene drought with corresponding extension of grassy plains or savannahs resulted in movement of pre-hominoid apes from the tree habitat on to the plains. No longer able to depend on lush vegetation in the forest, the savannah apes evolved an omnivorous diet scavenging for small game to satisfy their needs, later evolving into hunters. According to this theory, the one crucial development of bipedalism in the savannah ape evolved because of the advantage of standing upright on two legs and being able to see further over the plains and high grass in search of prey and to avoid predators. Later, the advantage of having two hands free to carry weapons enabled humans’ development as hunters in pursuit of game.11

But did we stand upright in order to hunt and kill big game on the plains of South Africa, as Dart and screen writer, Robert Ardrey have written?: ‘Man has emerged from the anthropoid background for one reason only, because he was a killer’.11 Or did we find a much less demanding environment where the food sat obligingly there on the river bed and sea floor for us to collect at our leisure without the need to chase after wild game and antelopes?6

One of the major weaknesses of the savannah theory is the disproportionate extent of major differences between humans and their ape cousins in physical and physiological characteristics, for example, bigger brains and bipedalism. If this suggested move on to the savannah and standing upright was so advantageous for one branch of the ape family, why have we not seen any similar or parallel developments in some of our primate cousins or in any other savannah mammal? None of the other apes have acquired even one of our unique characteristics. Other ape species have remained as gorillas and chimpanzees with few morphological or physiologic...