eBook - ePub

Tony White's Animator's Notebook

Personal Observations on the Principles of Movement

- 265 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

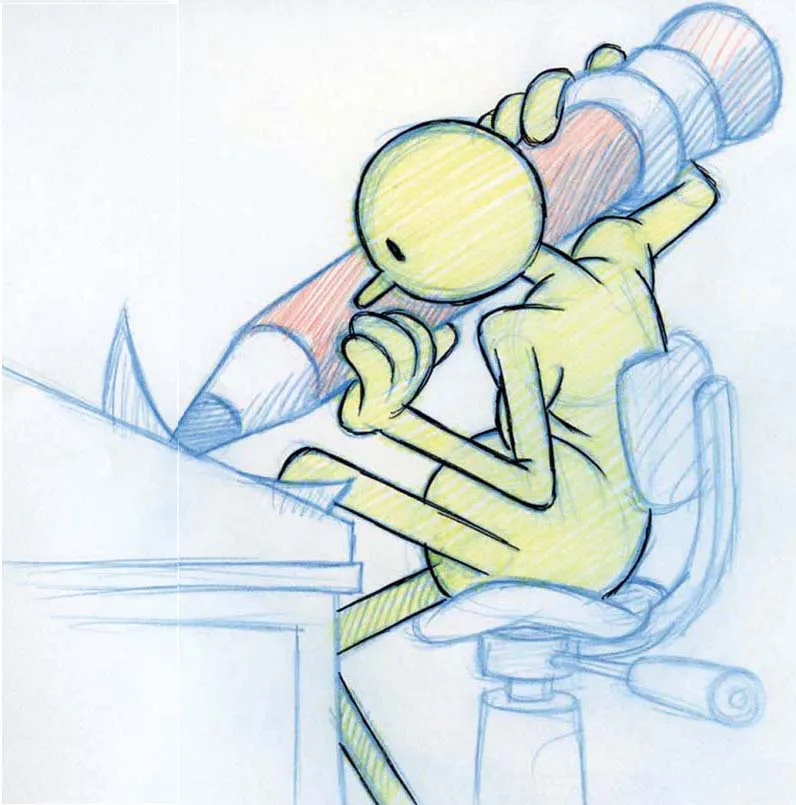

Apprentice yourself to a master of classical animation techniques with this beautiful handbook of insider tips and techniques. Apply age-old techniques to create flawless animations, whether you're working with pencil and animation paper or a 3D application.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tony White's Animator's Notebook by Tony White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Digital Media. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

The Principles and Process of Animation

Before you can tackle animation in any serious way, you need to understand the process and principles involved. The actual “process” of animation (i.e., the way the animator actually approaches the creation of scene) is hardly ever mentioned in literature on the subject, but it is extremely important, especially if character animation is your goal.

This chapter remedies this lack of information by explaining both the process and the principles of animation right from the get-go. Reading this part of my notebook will give you a foundation of method and information at your fingertips before you attempt the actual nitty-gritty of character animation in any serious way.

But first, let’s briefly review how we got to this moment in time with the finest art form known to humankind: animation!

Animation’s History in a Nutshell

The first animation was achieved by drawing the images directly onto film. This process involved every image on every frame of film being drawn slightly differently from the preceding one, like an old-fashioned paper flipbook.

This process of apparent movement was preceded by such fairground novelty devices as the Thaumotrope and the Practascope. However, it was not until Emil Cohl first drew images directly onto film that animation as we know it today—with direction, action, and story—was invented and captured the public’s imagination.

As time went by, a greater emphasis was placed on larger-scale drawings, initiated on paper, which were filmed and edited into short films. This gave both artists and filmmakers greater control over the subject matter, which meant that more finesse and complexity could be added to the action.

Typical of this era was the work of the great Winsor McCay, who drew incredibly complicated and intricate pen-and-ink drawings onto cards that were successively aligned and filmed afterward.

However, it was only when the animator’s peg bar was invented that a precisely registered process allowed for drawings to be consistently and universally created by a team of artists, using a key and “in-between” system, as defined in the early Fleischer Brothers’ cartoons, soon to be followed by those of the great Walt Disney.

Disney was responsible for moving the drawn cartoon tradition into entirely new areas of expression, in which a greater reality of characterization and innovative storytelling was developed to incredible degrees of innovation. Films such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi defined this amazing era, now often referred to as animation’s Golden Age.

Even today, with the amazing digital technology that is at the fingertips of every aspiring animator, we still use the same core principles of movement defined by keys, breakdowns, and in-betweens. As a result, any instruction that applies to the process and principles of animated movement is equally valid for every form of animation that is being attempted. Even the finest animators of the fabulous Pixar studio still pretty much adhere to the same production process that was used all those years ago by fabulous traditional 2D animators at the once great Disney studio.

The Process of Animation

The first question we must address is, how does a good character animator approach the creation of a scene within a production? There are, of course, as many approaches to the animation process as there are animators attempting it—and each animator evolves his or her own methods and procedures. However, what follows is a widely acknowledged generic approach that can apply to all animation formats, even though here we deal with the two principal forms of animation: traditional 2D animation and computer-based 3D animation.

The 2D Animation Process

Traditional 2D animation is no longer at the forefront of animation entertainment, but many passionate traditional animators still prefer the handcrafted, organic feel it offers when it’s executed well. For example, the recent Spirited Away movie, by Hayou Miyazaki, has to be considered one of the finest animated films ever made. Sylvan Chomet’s The Illusionist is another superbly crafted traditionally animated film. Certainly traditional animators at the top of their game still have a great deal to teach their more contemporary 3D counterparts, and much of its creative potential has yet to be realized, despite the infinite number of diverse films that have been produced traditionally over the decades.

What follows is the finest traditional animation process that I’ve personally found most valuable when approaching effective character animation. A modern student of traditional animated filmmaking will do well to follow the principles outlined here, even if they are later modified to suit that animator’s own particular preferences.

1. Understand what you need to achieve. This means that with whatever form of animation being attempted, the animator first must fully understand the story, the emotion, the motivation, the continuity (in other words, the scene with the scenes around it), and of course, the character acting needs for any particular scene. This can either be dictated by the director (in larger productions) or by the animators themselves on shorter, more personal films. Whatever the length or style of film being considered, however, it is a fundamental requirement of the process that the animators fully understand what they are seeking to achieve with each scene from the get-go.

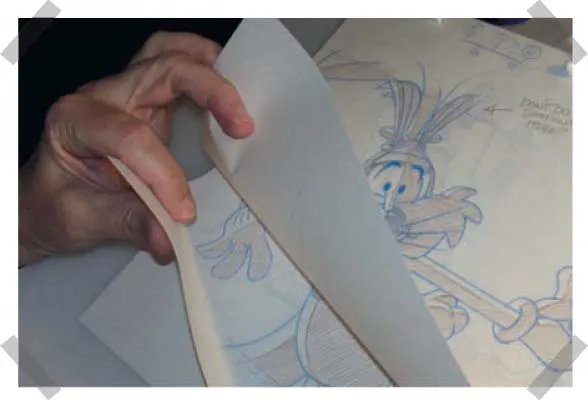

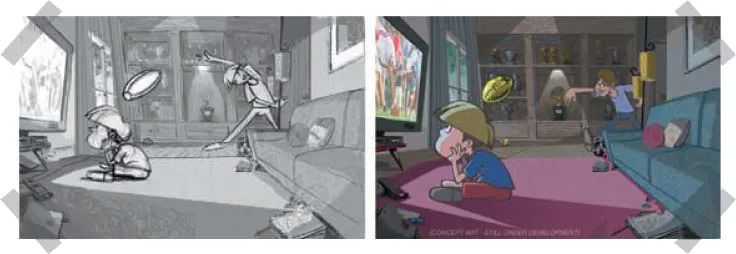

2. Key-pose thumbnails. To assist in the animators’ thinking process, it is highly desirable that they first produce a series of dynamic thumbnail key-pose positions for each character, expressing the kinds of dynamic key-pose gestures they have in mind for the action. These need not be perfectly crafted drawings, just freeform representations of the kinds of ideas that the animators feel best communicate what they are trying to achieve. However, in producing these thumbnails, the animators should not stop with the first ideas they think of or draw. They should push and push their visual pose ideas till something really gels in their mind. It is very often the case that the first thing thought of is not the best thing ultimately, so always push yourself at this decisive stage. When this goal is ultimately achieved, however, shoot your thumbnails in sequence as a rough-pose animatic.

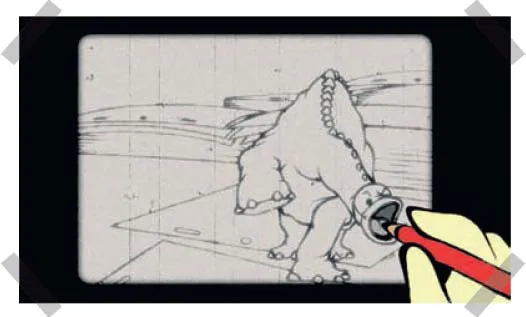

3. Reference video footage. It is very desirable that you find video footage of the action you are attempting, or even film yourself doing that same action in a number of ways. As with invaluable life drawing sessions, observing and recording real life is much superior to relying on memory, imagination, or assumption alone to make your final gesture statements. So, wherever possible, reference either live or filmed footage to give you greater insights into the kinds of key-pose gestures and elements of movement that you need to attempt.

Important note:

Never use footage as rotoscope or motion capture material only; this will only create dead and unconvincing animation, however economically desirable or time-consuming this option might appear at the outset. On the other hand, adjusted motion capture material after the event, achieved by an experienced professional animator, can raise the level of the final animated output through this technique, although the time taken to do this properly will probably be longer than if you had attempted to animate it from scratch in the first place!

4. Rough-pose animatic. With all your rough poses thumbed out, it is necessary to shoot them sequentially in a way that approximates the scene action you have in mind. Although there will be some inconsistencies with time and drawing-to-drawing scale in doing this, it will at least give you a general feel a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- DEDICATION

- CHAPTER 1 The Principles and Process of Animation

- CHAPTER 2 The Generic Walk

- CHAPTER 3 Stylized Walks

- CHAPTER 4 Personality Walks

- CHAPTER 5 Quadruped Walks

- CHAPTER 6 Generic Runs

- CHAPTER 7 Jumps

- CHAPTER 8 Weight

- CHAPTER 9 Arcs and Anticipation

- CHAPTER 10 Overlapping Action

- CHAPTER 11 Fluidity and Flexibility

- CHAPTER 12 Basic Dialogue

- INDEX