eBook - ePub

Agricultural System Models in Field Research and Technology Transfer

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agricultural System Models in Field Research and Technology Transfer

About this book

Most books covering the use of computer models in agricultural management systems target only one or two types of models. There are few texts available that cover the subject of systems modeling comprehensively and that deal with various approaches, applications, evaluations, and uses for technology transfer. Agricultural System Models in Field Res

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agricultural System Models in Field Research and Technology Transfer by Lajpat R. Ahuja,Liwang Ma,Terry A Howell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Whole System Integration and Modeling — Essential to Agricultural Science and Technology in the 21st Century

Lajpat R. Ahuja, Liwang Ma, and Terry A. Howell

CONTENTS

Current Status

The Future Vision

Integration of Modeling with Field Research

New Decision Support Systems

Collaborations for Further Developments

An Advanced Modular Modeling Framework for Agricultural Systems

References

CURRENT STATUS

Agricultural system integration and modeling have gone through more than 40 years of development and evolution. Before the 1970s, a vast amount of modeling work was done for individual processes of agricultural systems and a foundation for system modeling was built. For example, in soil water movement, models and theories were developed in the areas of infiltration and water redistribution (Green and Ampt, 1911; Philips, 1957; Richards, 1931), soil hydraulic properties (Brooks and Corey, 1964), tile drainage (Bouwer and van Schilfgaarde, 1963), and solute transport (Nielsen and Biggar, 1962). In plant-soil interactions, models and theories were developed for evapotranspiration (Penman, 1948; Monteith, 1965), photosynthesis (Saeki, 1960), root growth (Foth, 1962; Brouwer, 1962), plant growth (Brouwer and de Wit, 1968), and soil nutrients (Olsen and Kemper, 1967; Shaffer et al., 1969).

Although in the early 1970s, a few models were developed to include multiple components of an agricultural system, such as the model developed by Dutt et al. (1972), agricultural system models were not fully developed and used until the 1980s. In the 1980s, several system models were developed, such as the PAPRAN model (Seligman and van Keulen, 1981), CREAMS (Knisel, 1980), GOSSYM (Baker et al., 1983), EPIC (Williams and Renard, 1985), GLYCIM (Acock et al., 1985), PRZM (Carsel et al., 1985), CERES (Ritchie et al., 1986), COMAX (Lemmon, 1986), NTRM (Shaffer and Larson, 1987), and GLEAMS (Leonard et al., 1987). In the 1990s, agricultural system models were more mechanistic and had more agricultural components, such as CROPGRO (Hoogenboom et al., 1992; Boote et al., 1997), Root Zone Water Quality Model (RZWQM) (RZWQM Team, 1992; Ahuja et al., 2000), APSIM (McCown et al., 1996), and GPFARM (Ascough et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 2000). In addition, the new system models have taken advantage of current computer technology and come with a Windows™-based user interface to facilitate data management and model simulation. Some models are also linked to a decision support system (DSS), such as DSSAT which envelopes CERES and CROPGRO (Tsuji et al., 1994; Hoogenboom et al., 1999) and GPFARM (Shaffer et al. 2000). Agricultural system research and modeling are now being promoted by several international organizations, such as ICASA (International Consortium for Agricultural Systems Applications) and other professional societies.

The collective experiences from model developers and users show that, even though not perfect, the agricultural system models can be very useful in field research, technology transfer, and management decision making as demonstrated in this book. These experiences also show a number of problems or issues that should be addressed to improve the models and applications. The most important issues are:

1. System models need to be more thoroughly tested and validated for science defendability under a variety of soil, climate, and management conditions, with experimental data of high resolution in time and space.

2. Comprehensive shared experimental databases need to be built based on existing standard experimental protocols, and measured values related to modeling variables, so that conceptual model parameters can be experimentally verified.

3. Better methods are needed for determining parameters for different spatial and temporal scales, and for aggregating simulation results from plots to fields and larger scales.

4. The means to quickly update the science and databases is necessary as new knowledge and methods become available. A modular modeling approach will greatly help this process together with a public modular library.

5. Better communication and coordination is needed among model developers in the areas of model development, parameterization and evaluation.

6. Better collaboration between model developers and field scientists is needed for appropriate experimental data collection and for evaluation and application of models. Field scientists should be included within the model development team from the beginning, not just as a source of model validation data.

7. An urgent need exists for filling the most important knowledge gaps: agricultural management effects on soil–plant–atmosphere properties and processes; plant response to water, nutrient and temperature stresses; and effects of natural hazards such as hail, frost, insects, and diseases.

THE FUTURE VISION

Understanding real-world situations and solving significant agronomic, engineering, and environmental problems require integration and quantification of knowledge at the whole system level. In the 20th Century, we made tremendous advances in discovering fundamental principles in different scientific disciplines that created major breakthroughs in management and technology for agricultural systems, mostly by empirical means. However, as we enter the 21st century, agricultural research has more difficult and complex problems to solve.

The environmental consciousness of the general public is requiring us to modify farm management to protect water, air, and soil quality, while staying economically profitable. At the same time, market-based global competition in agricultural products is challenging economic viability of the traditional agricultural systems, and requires the development of new and dynamic production systems. Fortunately, the new electronic technologies can provide us a vast amount of real-time information about crop conditions and near-term weather via remote sensing by satellites or ground-based instruments and the Internet, that can be utilized to develop a whole new level of management. However, we need the means to capture and make sense of this vast amount of site-specific data.

Integration and quantification of knowledge at the whole-system level is essential to meeting all the above challenges and needs of the 21st century. Our customers, the agricultural producers, are asking for a quicker transfer of research results in an integrated usable form for site-specific management. Such a request can only be met with system models, because system models are indeed the integration and quantification of current knowledge based on fundamental principles and laws. Models enhance understanding of data taken under certain conditions and help extrapolate their applications to other conditions and locations. Models are the only way to find and understand the interrelationships among various components in a system and integrate numerous experimental results from different conditions.

System modeling has been a vital step in many scientific achievements. We would not have gone to the moon successfully without the combined use of good data and models. Models have been used extensively in designing and managing water resource reservoirs and distribution systems, and in analyzing waste disposal sites. Although a lot more work is needed to bring models of agricultural systems to the level of physics and hydraulic system models, agricultural system models have gone through a series of breakthroughs and can be used for practical applications, with some good data.

Integration of Modeling with Field Research

Integrating system modeling with field research is an essential first step to improve model usability and make a significant impact on the agriculture community. This integration will greatly benefit both field research and models in the following ways:

• Promote a systems approach to field research.

• Facilitate better understanding and quantification of research results.

• Promote quick and accurate transfer of results to different soil and weather conditions, and to different cropping and management systems outside the experimental plots.

• Help research to focus on the identified fundamental knowledge gaps and make field research more efficient, i.e., get more out of research per dollar spent.

• Provide the needed field test of the models, and improvements, if needed, before delivery to other potential users — agricultural consultants, farmers/ranchers, state extension agencies, and federal action agencies (NRCS, EPA, and others).

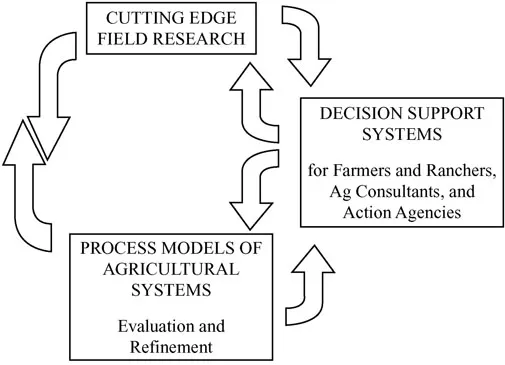

The most desirable vision for agricultural research and technology transfer is to have a continual two-way interaction among the cutting-edge field research, process-based models of agricultural systems, and decision support systems (Figure 1.1). The field research can certainly benefit from the process models as described above, but also a great deal from the feedback from the decision support systems (DSSs). On the other hand, field research forms the pivotal basis for models and DSSs. The DSSs generally have models as their cores (simple or complex).

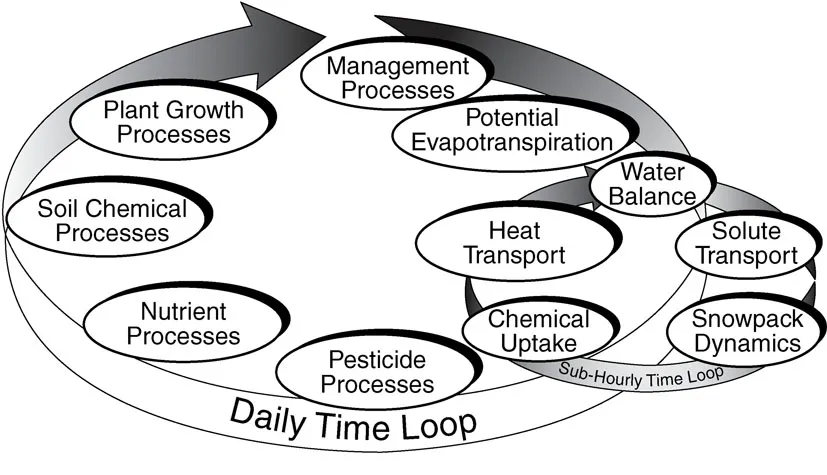

Modeling of agricultural management effects on soil-plant-atmosphere properties and processes has to be a center piece of an agricultural system model, if it is to have useful applications in field research and decision support for improved management. An example is the ARS Root Zone Water Quality Model (RZWQM), which was built to simulate management effects on water quality and crop production (Figure 1.2, Ahuja et al., 2000).

After a system model has passed the field testing and validation and both modelers and field scientists are satisfied with the results, it should be advanced to the second step: application. Only through model application to specific cases can a model be further improved by exposure to differing circumstances. The field-tested model can be used as a decision aid for best management practices, including site-specific management or precision agriculture, and as a tool for in-depth analysis of problems in management, environmental quality, global climate change, and other new emerging issues.

New Decision Support Systems

Decision support systems commonly have an agricultural system model at their core, but are supported by databases, an economic analysis package, an environmental impact analysis package, a user-friendly interface up front for users to check and provide their site-specific data, and a simple graphical display of results at the end. An example is the design of ARS GPFARM-DSS (Figure 1.3, Ascough et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 2000). GPFARM (Great Plains Framework for Agricul...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- The Editors

- Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Whole System Integration and Modeling — Essential to Agricultural Science and Technology in the 21st Century

- Chapter 2: Forage-Livestock Models for the Australian Livestock Industry

- Chapter 3: Applications of Cotton Simulation Model, GOSSYM, for Crop Management, Economic, and Policy Decisions

- Chapter 4: Experience with On-Farm Applications of GLYCIM/GUICS

- Chapter 5: Benefits of Models in Research and Decision Support: The IBSNAT Experience

- Chapter 6: Decision Support Tools for Improved Resource Management and Agricultural Sustainability

- Chapter 7: An Evaluation of RZWQM, CROPGRO, and CERES-Maize for Responses to Water Stress in the Central Great Plains of the U.S.

- Chapter 8: The Co-Evolution of the Agricultural Production Systems Simulator (APSIM) and Its Use in Australian Dryland Cropping Research and Farm Management Intervention

- Chapter 9: Applications of Crop Growth Models in the Semiarid Regions

- Chapter 10: Applications of Models with Different Spatial Scale

- Chapter 11: Modeling Crop Growth and Nitrogen Dynamics for Advisory Purposes Regarding Spatial Variability

- Chapter 12: Addressing Spatial Variability in Crop Model Applications

- Chapter 13: Topographic Analysis, Scaling, and Models to Evaluate Spatial/Temporal Variability of Landscape Processes and Management

- Chapter 14: Parameterization of Agricultural System Models: Current Approaches and Future Needs

- Chapter 15: The Object Modeling System

- Chapter 16: Future Research to Fill Knowledge Gaps

- Index