- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Why have so many central and inner cities in Europe, North America and Australia been so radically revamped in the last three decades, converting urban decay into new chic? Will the process continue in the twenty-first century or has it ended? What does this mean for the people who live there? Can they do anything about it?

This book challenges conventional wisdom, which holds gentrification to be the simple outcome of new middle-class tastes and a demand for urban living. It reveals gentrification as part of a much larger shift in the political economy and culture of the late twentieth century. Documenting in gritty detail the conflicts that gentrification brings to the new urban 'frontiers', the author explores the interconnections of urban policy, patterns of investment, eviction, and homelessness.

The failure of liberal urban policy and the end of the 1980s financial boom have made the end-of-the-century city a darker and more dangerous place. Public policy and the private market are conspiring against minorities, working people, the poor, and the homeless as never before. In the emerging revanchist city, gentrification has become part of this policy of revenge.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & LandscapingPart I

Toward a Theory of Gentrification

3

Local Arguments

From “Consumer Sovereignty” to the Rent Gap

Following a period of sustained deterioration in the postwar period, many cities began to experience the gentrification of select central and inner-city neighborhoods. Initial signs of revival during the 1950s, most notably in London and New York, intensified in the 1960s, and by the 1970s these had grown into a widespread gentrification movement affecting the majority of the larger and older cities in Europe, North America and Australia. Although gentrification rarely accounts for more than a fraction of new housing starts compared with new construction, the process is very important in those districts and neighborhoods where it occurs. And it has had a very powerful effect on the rethinking of urban cultures and urban futures in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Gentrification has etched the leading edge of the new urban frontier. If the comprehensive causes and effects of gentrification are rooted in a complex nesting of social, political, economic and cultural shifts, it is my contention here that the complexity of capital mobility in and out of the built environment lies at the core of the process. For all the interpretive cultural optimism that shrouds it, the new urban frontier is also a resolutely economic creation. The causes and effects of gentrification are also complex in terms of scale. While the process is clearly evident at the neighborhood scale it also represents an integral dimension of global restructuring. In this chapter 1 want to focus on explanations of gentrification at the neighborhood scale; Chapter 4 considers global arguments.

The Limits of Consumer Sovereignty

As the process of gentrification burgeoned so did the literature about it. The preponderance of this literature concerns the contemporary processes or its effects: the socioeconomic and cultural characteristics, profiles of the new urban immigrants, displacement, the role of the state, benefits to the city, the creation and destruction of community. At least in the beginning, little attempt was made to construct historical explanations of the process, to study causes rather than effects. Instead, explanations were very much taken for granted and have generally fallen into two categories: cultural and economic.

Popular among gentrification theorists is the notion that young, usually professional, middle-class people have changed their lifestyle. According to Gregory Lipton, for example, these changes have been significant enough to “decrease the relative desirability of single-family, suburban homes” (1977:146). Thus, with the trend toward fewer children, postponed marriages and a fast-rising divorce rate, younger homebuyers and renters are trading in the tarnished dream of their parents for a new dream defined in urban rather than suburban terms. Others have emphasized the search for socially distinctive communities, as in the case of gay gentrification (Winters 1978; Lauria and Knopp 1985), while still others have extended this into a more general argument. In contemporary “post-industrial cities,” according to David Ley, where white-collar service occupations supersede blue-collar productive occupations, this brings with it an emphasis on consumption and amenity, not work. Patterns of consumption come to dictate patterns of production; “the values of consumption rather than production guide central city land use decisions” (Ley 1978:11; 1980). Gentrification is explained as a consequence of this new emphasis on consumption. It represents a new urban geography for a new social regime of consumption. Earlier cultural explanations of this sort have been supplemented more recently by the tendency to treat gentrification as an urban expression of postmodernity or (in more extreme cases) postmodernism (Mills 1988; Caulfield 1994).

Over and against these cultural explanations are a series of closely related economic arguments. As the cost of newly constructed housing has risen rapidly in the postwar city and its distance from the city center increased, the rehabilitation of inner- and central-city structures is seen to be more viable economically. Old properties and housing plots can be purchased and rehabilitated for less than the cost of a comparable new house. In addition, many researchers, especially in the 1970s, stressed the high economic cost of commuting—the higher cost of gasoline for private cars and rising fares on public transportation—and the economic benefits of proximity to work.

These conventional hypotheses are by no means mutually exclusive. They are often invoked jointly and share in one vital respect a common perspective: an emphasis on consumer preference and the constraints within which these preferences are implemented. This assumption of consumer sovereignty is shared with the broader rubric of residential land use theory emanating from postwar neoclassical economics (Alonso 1964; Muth 1969; Mills 1972). According to these theories, suburbanization reflects the preference for space and the increased ability to pay for it due to the reduction of transportational and other constraints. Gentrification, then, is explained as the result of an alteration of preferences and/or a change in the constraints determining which preferences will or can be implemented. Thus in the media and the research literature alike, and especially in the US, where suburbanization bore such a heavy cultural symbolization, gentrification came to be viewed as a “back to the city movement.”

This assumption applied as much to the earlier gentrification projects, such as Philadelphia’s Society Hill (accomplished after 1959 with substantial state assistance— see Chapter 6), as it does to the later more spontaneous and more ubiquitous emergence of gentrification in the private market (albeit often still with public subsidies). All have become symbolic of a supposed middle-and upper-class pilgrimage back from the suburbs. And yet the pervasive assumption that the gentrifiers are disillusioned suburbanites may not be accurate. As early as 1966, Herbert Gans lamented the lack of any “study of how many suburbanites were actually brought back by urban renewal projects” (1968:287), and in subsequent years academic studies began to research the issue.

In the first part of this chapter, then, I present some empirical information from Society Hill in Philadelphia as a means of challenging the traditional consumer sovereignty assumptions expressed by the “back-to-the-city” nomenclature. The next section examines the importance of capital investment for the shaping and reshaping of the urban environment, and this is followed by an analysis of disinvestment—a vital but widely ignored determinant of urban change. Finally, I try to bring these themes together in the proposal of a “rent gap” hypothesis for the explanation of gentrification.

A Return from the Suburbs?

The location of William Penn’s “holy experiment” in the seventeenth century, Society Hill housed Philadelphia’s gentry well into the nineteenth century. With industrialization and urban growth, however, its popularity declined, and the gentry, together with the rising middle class, moved west of Rittenhouse Square, and across the Schuylkill River to West Philadelphia, and to the new suburbs in the northwest. Society Hill deteriorated rapidly toward the end of the nineteenth century, being effectively written off as a “slum” neighborhood (Baltzell 1958). In the 1950s, however, a new city administration aligned itself with a patrician ambition for renewal, and in 1959 an urban renewal plan was implemented. Within ten years Society Hill was transformed. Described seventeen years later in Bicentennial advertising as “the most historic square mile in the nation,” Society Hill again came to house the city’s middle and upper middle classes and even a few members of the upper classes. Noting the enthusiasm with which rehabilitation was done, the novelist Nathanial Burt captured the elite flavor of many of the early US gentrification projects.

Remodeling old houses is, after all, one of Old Philadelphia’s favorite indoor sports, and to be able to remodel and consciously serve the cause of civic revival all at once has gone to the heads of the upper classes like champagne.”

(Burt 1963:556–557)

As this indoor sport caught on, therefore, it became Philadelphia folklore that “there was an upper class return to center city in Society Hill” (Wold 1975:325). Burt eloqu0ently explains in the still novel but emerging language of civic boosterism:

The renaissance of Society Hill…is just one piece in a gigantic jigsaw puzzle which has stirred Philadelphia from its hundred-year sleep, and promises to transform the city completely. This movement, of which the return to Society Hill is a significant part, is generally known as the Philadelphia Renaissance.

(Burt 1963:539)

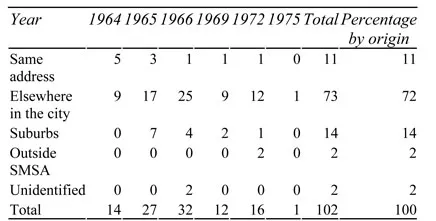

In fact, by June 1962 less than a third of the families purchasing property for rehabilitation were from the suburbs1 (Greenfield and Co. 1964:192). But since the first people to rehabilitate houses began work in 1960, it was generally expected that the proportion of suburbanites would rise sharply as the area became better publicized and a Society Hill address became a coveted possession. After 1962, however, no data were officially collected. Table 3.1 presents data sampled from case files held by the Redevelopment Authority of Philadelphia, covering most of the first fifteen years of the project, by which time it was essentially complete. It represents a 17 percent sample of all rehabilitated residences.

Table 3.1 The origin of rehabilitators in Society Hill, Philadelphia, 1964–1975

Source: Redevelopment Authority of Philadelphia case files

Note: SMSA=Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area

It would appear that only a small proportion of gentrifiers—14 percent—did in fact return from the suburbs to Society Hill. By comparison, 72 percent moved from elsewhere within the city boundaries. A statistical breakdown of this latter group suggests that of previous city dwellers, 37 percent came from Society Hill itself, and 19 percent came from the fashionable Rittenhouse Square district alone. The remainder came largely from several middle- and upper-class neighborhoods in the city: Chestnut Hill, Mount Airy, Spruce Hill. Rather than a return from the suburbs, this would seem to suggest that gentrification is bringing about a recentralization and reconsolidation of upper- and middle-class white residences in the city center. A similar pattern of consolidation can be observed in several of the cities surveyed by Lipton (1977). Additional data from Baltimore and Washington, DC, on the percentage of returning suburbanites support the Society Hill data (Table 3.2). In a European context, similarly, Cortie et al. (1982) find very little evidence of a “return to the city” in connection with the gentrification of the Jordaan district of Amsterdam (see Chapter 8).

Table 3.2 The origin of rehabilitators in three cities

| City | Percentage of city dwellers | Percentage of suburbanites |

| Philadelphia: Society Hill | 72 | 14 |

Baltimore Homestead | 65.2 | 27 |

Properties Washington, DC | ||

Mount | 67 | 18 |

| Pleasant Capitol Hill | 72 | 15 |

Sources: Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development 1977; Gale 1976, 1977

In Philadelphia and elsewhere an “urban renaissance” of sorts may well have begun in the 1950s and 1960s, but it was not fueled by any significant return of the middle class from the suburbs. Even at the height of 1980s gentrification, suburban expansion proceeded apace. This would seem to cast doubt on the traditional cultural and economic explanations of gentrification as the result of altered consumer choices amid economic constraints. It is not that consumer choice is unimportant; in one scenario, it is possible that some gentrification involves younger people who moved to the city for an education and professional training in the decades after the 1950s but who did not then follow their parents’ migration to the suburbs, becoming instead a social reservoir from which the gentrifier demand grew. If a dimension of consumer choice certainly remains, consumer sovereignty is more difficult to defend as a definitive explanation for gentrification. The problem is that gentrification is not simply a North American phenomenon but also emerged in the 1950s and 1960s in Europe and Australia (see, for example, Glass 1964; Pitt 1977; Kendig 1979; Williams 1984b, 1986), where the extent and experience of prior middle-class (and indeed working-class) suburbanization and the relation between suburb and inner city are substantially different. Only Ley’s (1978) more general societal hypothesis about postindustrial cities is broad enough to account for the process internationally while retaining a consumption-centered approach, but the implications of accepting this view are somewhat drastic. If cultural choice and consumer preference really explain gentrification, this amounts either to the hypothesis that individual preferences change in unison not only nationally but internationally—a bleak view of human nature and cultural individuality—or that the overriding constraints are strong enough to obliterate the individuality implied in consumer preference. If the latter is the case, the concept of consumer preference is at best contradictory: a process first conceived in terms of individual consumption preference has now to be explained as resulting from cultural unidimensionality in the middle class—still rather bleak. At best, then, a focus on consumption can be rescued as theoretically viable only if it is used to refer to collective social preference, not individual preference.

The broader critique of the theory and assumptions underlying traditional urban economic theory is now well known (Ball 1979; Harvey 1973; Roweis and Scott 1981). I want here just to consider one particular aspect of neoclassical theory as it is applied to neighborhood change, leading to gentrification. To explain contemporary changes in the inner-city housing market, Brian Berry among others resorts to a “filtering” model. According to this model, new housing is generally occupied by better-off families who vacate their previous, less spacious housing, leaving it to be taken by poorer occupants, and move out toward the suburban periphery. In this way, decent housing “filters” down and is left behind for lower-income families; the worst housing drops out of the market to abandonment or demolition (Berry 1980:16; Lowry 1960). Leaving aside entirely the question whether this “filtering” in fact guarantees “decent” housing for the working class, the filtering model is clearly based on a historicization of the effects of consumer sovereignty. People possess a set of consumer preferences, including a preference for more and more residential space, the model assumes, and so the greater one’s ability to pay for space, the more space one will purchase. Smaller, less desirable spaces are left behind for those less able to pay. Other factors certainly impinge on demand for housing as well as its supply, but this preference for space together with the necessary income constraints provide the foundation for neoclassical treatments of urban development.

Gentrification contradicts this foundation of assumptions. It involves a so-called filtering in the opposite direction and seems to contradict the notion that preference for space per se is what guides the process of residential development. This means either that this assumption should be dropped from the theory or that so-called “external factors” and income constraints were so altered as to render the preference for more space impractical and inoperable. It is in this way that gentrification is rendered an exception— a chance, extra-ordinary event, the accidental outcome of a unique mix of exogenous factors. But in reality gentrification is not so extraordinary; it is extraordinary only to the theory which assumes it impossible from the start. The experience of gentrification illustrates well the limitations of neoclassical urban theory since in order to explain the process, the theory must be abandoned, and a superficial explanation based on ad hoc external factors must be adopted. But a list of factors does not make an explanation. The theory claims to explain suburbanization but cannot at all explain the historical continuity from suburbanization to gentrification and inner-city gentrification. Berry implicitly recognizes the need for (but lack of) such historical continuity when he concludes:

a restructuring of incentives played a critical role in the increase in home ownership and the attendant transformation of urban form after the Second World War. There is no reason to believe that another restructuring could not be designed to lead in other directions, for in a highly mobile market system nothing is as effective in producing change as a shift in relative prices. There is, then, a way. Whether there is a will is another matter, for under conditions of democratic pluralism, interest group politics prevail, and the normal state of such politics is “business as usual.” The bold changes that followed the Great Depression and the Second World War were responses to major crises, for it is only in a crisis atmosphere that enlightened leadership can prevail over the normal business of politics in which there is an unerring aim for the lowest common denominator. Nothing less than an equivalent crisis will, I suggest, enable the necessary substantial inner city revitalization to take place.

(Berry 1980:27–28).

In this way Berry shares with optimistic proponents of the process a voluntarist explanation of gentrification.

This critique of the neoclassical assumptions implicit in much gentrification research is partial and far from exhaustive. What it suggests, however, is the need for a broader conceptualization of the process, for the gentrifier as consumer is only one of many actors participating in the process. To explain gentrification according to the gentrifier’s preferences alone, while ignoring the role of builders, developers, landlords, mortgage lenders, government agencies, real estate agents—gentrifiers as producers—is excessively narrow. A broader theory of gentrification must take the role of the producers as well as the consumers into account, and when this is done it appears that the needs of production—in particular the need to earn profit—are a more decisive initiative behind gentrification than consumer preference. This is not to say in some naive way that consumption is the automatic consequence of production, or that consumer preference is a totally passive effect of production. Such would be a producer’s sovereignty theory, almost as one-sided as its neoclassical counterpart. Rather, the r...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Toward a theory of gentrification

- Part II The global is the local

- Part III The revanchist city

- 10 FROM GENTRIFICATION TO THE REVANCHIST CITY

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The New Urban Frontier by Neil Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.