Dreamtelling

It all started with my connection to my dreaming and my interest in the relations between the dream’s content and the relational context in which it is remembered and told. Two ‘events’ helped me to define my own thinking on dreamtelling (Friedman, 2008). The first was when my son was about three or four years old, and often woke up from what seemed to be a nightmare. His nocturnal cries made me jump out of my bed and rush into his room. He usually returned to sleep in a moment – while I was left worried, especially if this repeated itself in the same night. I learned from this ‘interaction’ about the non-verbal communication of anxiety and panic, and even more about the possibility that feelings can be shared between a dreamer and his audience. Later I understood that these are more familiar situations than we think. I called my son’s communication a ‘request for containment’; I understood that I was the ‘container-on-call’ and that there was a very deep relation between the two of us.

The other event which helped me to understand the deeper communicative aspects of dreamtelling was a patient’s story: he fell for a young woman in a party, but could not find enough courage to approach her directly. Back home, he dreamt about her with red lips, which seemed to be waiting for a kiss … and in his dream they did indeed have a passionate kiss. Although first his dream just felt like ‘wishful thinking’ there was a completely additional side to the dream in this story. In our area, party participants used to meet on the beach the next afternoon. Then, ‘armed’ with this dream, he found the courage to approach the young woman and conquer her heart by sharing his dream with her. It was only much later that I could conceptualize what seemed to be a banality: the dream’s power to demand to influence a relationship. Understanding the ‘told’ dream’s unconscious communication as a wish to change the relations with the audience helped me to further clarify ‘transformative’ sides in dreamtelling. Dreams are not only informative, but have the power to transform relations. Later I understood the general clinical value of understanding much of human communications as ‘requests for containment’ and ‘demands for transformation of relations’.

By dreamtelling I refer to a whole elaboration process, which starts with a dreamer’s autonomous effort to elaborate excessive emotions during sleep, and finishes by further elaborating these excessively strong emotions through sharing the dream with a co-operative audience. Dreams may be remembered and told to others, and also resonate with others. While usually dreams told in therapy seem to request an interpretation, in my clinical experience I found that not every dreamer is ready for an interpretation, nor are the relations with the dreamer ready for touching the unconscious. Finally, we have to acknowledge that simple human resonance is often more needed than deep interpretation (Friedman, 2006).

This insight helped me to define what it means to work ‘formatively’: when we feel the dreamer is in some danger of fragmentation, or in crisis, etc. We should use the dream told in order to first strengthen the dreamer’s Self. Dreamtelling can call for a first ‘forming’ or structuring of the relation between all participants. That is one reason why I often suggest that our reactions to a dream told should be ‘re-dreaming the dream’ as if it was the listener’s own dream.

Dreams are the result of a special kind of mental ‘digestion’ of excessively threatening and/or exciting emotions. It is an adaptive system, functional and natural for humans like the process of breathing oxygen. Later they may be adapted into our being or thinking – sometimes in order to enjoy them. By magically translating emotions and thoughts into stories, scripts, images, known or wished relations and voices, dreams are created. Research maintains that most probably our unconscious elaboration makes use of our whole lifetime experience, by comparing past and present situations.

My first professional encounter with dreams was influenced by the classical approach to the dream as a text. What first drew my attention were the dream’s contents, I suppose much in in the same way as Freud’s (1900) traditional, ‘diagnostic’ approach, which I later renamed as ‘informative’. Many of us who are interested in dreams, are first fascinated by unveiling the unconscious, to get more knowledge of the dreamer’s psyche, to decipher latent contents like the Rosetta Stone. Soon another interest awoke in me and I asked: In which unique way does the dream itself reveal how the dreamer copes with his difficulties? Together with Morgenthaler (1986) and others, I felt the creation of the dream and its structure would characterize the dreamer more than we thought.

But the information which interested me quickly led me into more interactional realms. Firstly, I asked if every dreamer is able to profit from deep interpretation. My clinical experience showed this is in no way so. In this book I try to give guidance as to who could be harmed from interpretation, and how to determine this ahead of time. Dreamtelling also makes it potentially possible to find partners who could co-operate. Dreams send powerful conscious and unconscious messages which influence the dreamer’s relation with the audience. As we discovered in our research, this is also true of new partnerships.

I learned that not all of the dream’s contents are told into the transference, and therefore are not exclusively directed at the listening therapist. Although this often happens, dreamtelling is more connected to requests for containment and further elaboration. Dreamtelling is also more than merely a tool for the elaboration of excessive emotions, but the creation of relations and partnerships and their transformation. This alone makes dreamtelling a fascinating and complex interpersonal event. Dreams suddenly went beyond being ‘the royal way to the dreamer’ and became ‘the royal way to the dreamer’s psyche through his relations with others’. The strangest part was when it became clear that the dreamer was not only dreaming for himself but had been called upon to elaborate emotional difficulties of others too. It is always his own problem, but this new understanding that our dreaming may ‘borrowed’ by those close to us is actually mind blowing. A child, a friend or a patient may ask the dreamer to digest his uncontained problem. In therapy groups it makes shared work reciprocally significant.

Working with dreams does not need magical endowment or witchcraft. It can be learned. As a rule, when there is a container, dreams are better remembered and shared. When dreams are shared in families or groups, they overcome modern culture’s malady of disconnection with our inner life. Participants in ‘dream-groups’ seem to get in touch with the dreams’ complexity and richness and progressively befriend dreamtelling to develop a better elaboration of difficult emotions. I learned much from dream-groups, where the therapeutic work is done through sharing dreams and responding to them, as if they were ‘your own dream’. In therapeutic groups which include dreamtelling, the relations become qualitatively different.

The theatre of the mind (Resnik, 2002) becomes the dream stage where group experiences both influence and are elaborated. S.H. Foulkes (1964) himself did not move far from the traditional early psychoanalytic thinking on dreams which emphasized contents. In fact, dreamtelling works in a way that promotes identification processes with the dreamer, and can be considered to be a model for group-analytic work. It makes optimal use of the group as a source for mirroring and resonance, creating within the group a certain music around dreams, which has to be played and heard to connect to it emotionally.

The chapter on research describes an investigation we made at Haifa University asking 100 men and 100 women about their family history, personal past, and the present patterns of dreamtelling. Particularly interesting were connections made between parental containment of their children’s dreams and subsequent ability to relate to the inner world in general and dreams in particular. There was significant evidence of transgenerational transmission of the ability to share dreams. After we understood the developmental significance of sharing dreams, it also became clear that most modern families do not have the know-how to listen and react to children’s dreams in a way which furthers communication, rather than shame, guilt or manipulation. Individuals, couples and families who own some ability to work in a dreamtelling ‘fashion’ seemed to profit from great emotional communicative advantages. For example, men in love tell unusually more dreams to their new partners, something which also shows that they feel to have found a container and are unconsciously prone to influence the growing relationship.

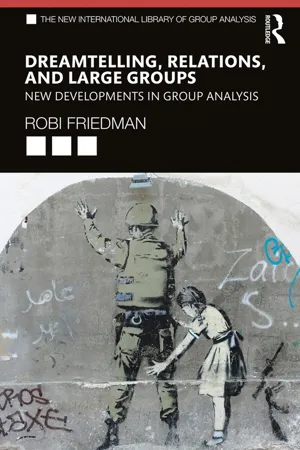

My own long story with conflict resolution started more than 20 years ago with a difficulty to shake the hand of a Palestinian professional. In the years after that, I went through a lot of pain and elaboration of many difficult feelings, especially hate, shame and the most difficult feeling of all: guilt. The ‘guilt war’: the ability to accuse the other side along with the difficulty to accept one’s own guilt (Friedman, 2015). This seems to me to be the most significant obstacle to talks with former ‘enemies’. It requires not only personal transformative processes to overcome the destructivity of such a war, but also a special social situation which supports the feelings of guilt. In many settings, I have tried and still do try to meet hate and accusations from the ‘other side’. Dreams where more than one side is represented helped me to be able to understand and contain the ‘other’ side and the feelings aroused. In fact, we can often see how dreams, when elaborated as a dialogue between differing and conflicting aspects in ourselves and in society, become as close to a conflict resolution dialogue as they can be.