![]()

1 Introduction: Situating Monuments

The Dialogue Between Built form and Landform in Atlantic Europe

Chris Scarre

The Atlantic coastline of Europe, from the Straits of Gibraltar to North Cape, presents for the most part a landscape of craggy granitic headlands and narrow marine inlets punctuated by low-lying basins and estuaries giving access to the interior. Traditional similarities between the coastal communities of Galicia, Brittany, Ireland and western Britain have given rise to the idea that these areas share a common heritage, linked by their proximity to the sea. This Atlantic identity – if such it is – may have been forged by millennia of maritime contact, but could also owe much to the special character of the Atlantic fringe in itself, as the land at the edge of the world, beyond which there was nowhere to go. It has recently been suggested that such factors may have induced the formation of a characteristic Atlantic mind-set as long ago as the Mesolithic period (Cunliffe 2001, 155). There are certainly archaeological parallels in such features as passage graves to suggest a measure of contact between Portugal and Scandinavia in the Neolithic, and sea-borne contacts can be pursued by archaeology into later periods through the evidence of Maritime Beakers, Atlantic bronzes and the tin trade.

Language, too, has been brought into the equation, ever since the recognition in the 18th century that the earliest attested languages of the Atlantic fringe bear a family relationship to each other. The ‘Celtic’ languages of Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany are the survivors of a once more extensive series of languages which included Celtiberian and Gaulish. It is likely, indeed, that by the middle of the 1st millennium BC, the peoples living along the Atlantic seaboard from northern Scotland to the Straits of Gibraltar were speaking related languages which may for convenience be described as ‘Atlantic Celtic’ (Cunliffe 2001, 296). Whether this language pattern was spread by farmers from the east or through maritime contact along the seaboard (or more likely perhaps a mixture of both), remains undecided, as indeed does its antiquity, but the impact of a sense of ‘Celtic’ identity on recent historical and political awareness in many parts of Atlantic Europe is beyond question.

Living on the edge of the limitless ocean may have inspired and informed particular notions of cosmology and geography, both sacred and secular. While at one level this will have formed a common basis for human experience on the Atlantic fringe, it is important also to recognise the highly diverse character of the Atlantic margin. Islands and inlets, crags and moors make up a richly accentuated and often spectacular landscape, but it must not be forgotten that the lowlands of Aquitaine, fringed by long coastal sand dunes, are no less a part of Atlantic Europe than the cliffs and estuaries of the granitic massifs. Furthermore, Atlantic Europe consists of much more than a narrow coastal strip, and however significant the proximity of the sea in many parts of this broad region, traditional communities in inland and upland areas were as landlocked as any in Europe until the arrival of the railways and the transport revolution.

We must then beware of any essentialist notion of Atlantic Europe as a ‘natural’ entity. Its diversity in peoples, traditions and landscapes has been a feature since early prehistoric times. Yet it is also clear that the lands bordering the Atlantic were during the 5th and 4th millennia BC the setting for the construction of monuments, mainly funerary in character, which marked a visible break with the past. Long mounds in Britain, Brittany and Scandinavia, passage graves from Portugal to Sweden, rows and rings of standing stones, all mark a significant rupture with what had gone before, and the beginning of something new. Questions of origins are no longer so fashionable in archaeology as once they were, yet the transformations that lay behind the development of early Atlantic monuments remain a central focus of research. One part of the answer must be sought in the changes which European societies underwent in the course of the 6th and 5th millennia BC. These were associated with the spread of plant and animal domesticates, even though the notion that it was farming that made monuments possible may now be rejected. It is clear, in any event, that monuments in other parts of the world were not beyond the capabilities of hunter-gatherer groups. Examples range from the stone-built Inuksuit of Baffin Island, Canada, still being erected in recent times to signpost significant locations, back to the burial mound (dated to c.7500 bp) at L’Anse Amour on the Strait of Belle Isle in southern Labrador (McGhee and Tuck 1975, 85–94; Hallendy 2000). Aboriginal societies of Australia, too, created monumental structures for mortuary rituals or religious ceremonies: huge carved grave posts among the Tiwi of northern Australia; large earth sculptures at the ‘bora’ grounds of New South Wales; and settings of stone blocks, such as the 50m long line with associated circles and ‘corridors’ at Namagdi near Canberra (Flood 1995, 274–6). Yet in the west European context, the Neolithic monuments have no such Mesolithic antecedents. Notwithstanding rare discoveries like the line of massive Mesolithic posts in the Stonehenge car park (Cleal et al. 1995, 42–7), or the modest tumuli of the Mesolithic cemetery at Téviec (Péquart et al. 1937), there is simply nothing in Mesolithic Atlantic Europe to compare with the number, diversity and scale of Neolithic monuments.

Earlier prehistorians such as Gordon Childe invoked ‘megalithic missionaries’ to explain the origins and distribution of the Atlantic megaliths. Starting in the Mediterranean, he imagined groups of sailors travelling northwards along the Atlantic coast bringing a new religion and the monumental settings that it demanded (Childe 1958, 124–34). Later interpretations have substituted marine resources for religious zeal in explaining these monuments, suggesting that the pursuit of migratory fish may have brought communities into close contact with each other in such a way as to encourage the spread of concepts and technologies (Clark 1977). Alternative perspectives have seen the shared quality of the Atlantic lands to lie in their character of periphery to a central European core. Thus megalithic monuments may have arisen independently in different areas of Europe through common response to the pressure of farming groups arriving from the east (Renfrew 1976); or through the persuasive power of a dominant ideology based on the concept of linearity embedded in the central European longhouse (Hodder 1990).

What these explanations lack is attention to the specific forms and settings of individual monuments. They in no way help us to understand why communities chose to build these particular kinds of monument, using the materials that they did. Recent studies have begun to explore this question by considering explicitly how the monuments relate to their physical surroundings. Behind this approach lies a single fundamental concept: that the intrinsic qualities encountered within the diverse landscapes of this western margin of Europe informed both the settings chosen for the monuments and played a part in determining their form and visual appearance. This in part derives from the use of local materials, and the manner in which these were displayed within the monuments: the way in which they might incorporate stone, for example, which was visibly taken from the local geology. Yet we may go further than this and propose that in some instances the nature of local landforms did themselves both attract monuments, providing meaningful or dramatic locations, and provide a series of ideas which played some part in influencing the form of those monuments.

Approaches to Landscape in Atlantic Europe

The character of a particular landscape must be apparent to any archaeological field worker who has battled through rain and sun, across fields and ditches, up craggy slopes or gently shelving valleys, to locate and excavate prehistoric sites. Agricultural potential and the availability of local resources such as clay, stone or metal are frequently invoked. Yet few fieldwork reports attempt to understand the symbolic or cosmological significance of a particular location. There may perhaps be the fear that such comments would be regarded as unscientific, verging dangerously on an empathetic understanding of the past. But monuments do have specific locations and those locations would have been meaningful in a variety of ways to the communities that built them, and to their successors in both prehistoric and historical periods. The manifest difficulty of interpreting these associations should not lead to their being studiously ignored.

In southern Britain, the beginnings of archaeological fieldwork were characterised by the careful observation of several major monuments by antiquarians such as John Aubrey and William Stukeley. The plans which they prepared could be considered the first in a series of modern Western abstractions which however much they inform, may also be leading away from the monuments as they are encountered and experienced in their materiality (Thomas 1990; Tilley 1994, 75; Barrett 1994, 12ff). Stukeley, however, was fully aware of the more emotive qualities of the Wiltshire landscape:

The strolling for relaxed minds upon these downs is the most agreeable exercise and amusement in the world especially when you are every minute struck with some piece of wonder in antiquity. The neat turn of the huge barrows wraps you up into a contemplation of the flux of life and passage from one state to another and you meditate with yourself of the fate and fortune of the famous personages who thus took care of their ashes that have rested so many ages.

(Stukeley, quoted in Piggott 1985, 154)

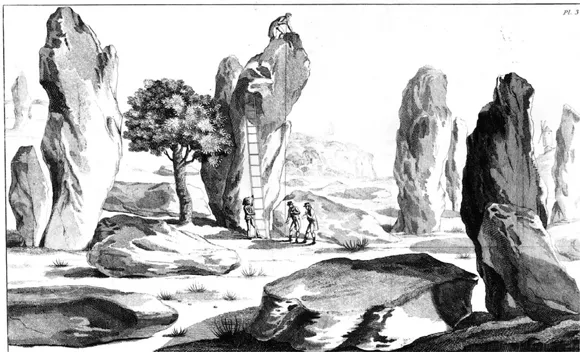

Similar sensitivities are perhaps still more evident in illustration than prose; the early engravings of the Carnac alignments which accompanied Jacques de Cambry’s (1805) Monumens celtiques, ou recherches sur le culte des pierres, for example, appear to show a striking awareness of close resemblances – which we may term a kind of resonance – between the built structures and the natural rock formations, albeit the latter in the form depicted by Cambry, owe a great deal to the imagination (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Carnac alignments from Cambry, Monumens celtiques.

As archaeology became established as an academic discipline in the early 20th century, a more analytical view of landscape at a much larger scale emerged. One influential work was The Personality of Britain (Fox 1932), with the revealing subtitle Its influence on inhabitant and invader in prehistoric and early historic times. In this study Cyril Fox sought to relate patterns of prehistoric settlement to regional patterns of soils and geology, drawing the distinction between the highland and lowland zones of Britain. The development of aerial archaeology, too, encouraged the appreciation of landscapes as palimpsests of archaeological sites and monuments. At the smaller scale, there was recognition of ‘archaeological landscapes’ where clusters of monuments were found within a restricted compass, as for example the Avebury area, the Boyne Valley or Carnac in Brittany. Few if any of these studies, however, sought to consider in detail the meaning of the specific landscapes themselves for prehistoric and early historical communities.

The study of the relationship of individual monuments to particular features of the landscape probably arose first in the context of astronomical interpretations. It was William Stukeley, again, who in 1723 first recorded that the principal axis of Stonehenge was aligned upon the midsummer sunrise. More recently, considerations of landscape – in the shape of distant or mountainous horizons – came prominently to the fore in the surveys carried out by Alexander Thom in Britain and Brittany in the 1960s and 1970s (Thom 1967, 1971; Thom and Thom 1978). Many of these relied on the path of sun or moon at particular days of the year, and the way that the solar or lunar disc at rising or setting clipped the edge of a hill or a notch between mountains on the horizon. Sites such as Kintraw in Argyll were interpreted as megalithic observatories. Many of these claims do not stand up well to critical assessment; above all, the high precision alignments that Thom proposed are now generally discounted (Ruggles 1999). There remains the general principle, however, that early societies were aware of the movements of the heavenly bodies, and incorporated them into their cosmologies. These in turn will have entered into the design and placement of individual monuments. Astronomy and statistics play a key part in developing and assessing these claims; yet the fundamental question at issue is one of prehistoric belief systems, and how societies experienced and understood their surroundings be they land, sea or sky.

The study of prehistoric monuments entered a new phase in the 1990s with the development of phenomenological approaches, drawing on the work of Continental philosophers Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty. In seeking to explore the description and understanding of things as they are experienced by a (prehistoric) subject, phenomenological approaches are, by their very nature, subjective. A key contribution was Chris Tilley’s A Phenomenology of Landscape (1994), which discussed the philosophical and ethnographic background, and proceeded to apply it to the study of Neolithic monuments in three regions of southern Britain: south-west Wales, the Black Mountains and Cranborne Chase. Tilley sought to underline ‘the affective, emotional and symbolic nature of the landscape and [to] highlight some of the similarities and differences in the relationship between people and the land, and the manner in which it is culturally constructed, invested with powers and significances, and appropriated in widely varying “natural” environments and social settings’ (Tilley 1994, 35). This concept of the ‘numinous landscape’ where places and landforms are imbued with mythological or spiritual significance is familiar from a number of ethnographic accounts and is indeed a feature of recent European folklore. It must be considered particularly appropriate to the consideration of prehistoric monuments which are thought to embody ritual practices and cosmological beliefs. The subjectivity of the phenomenological approach, however, presents considerable obstacles in methodology. Fleming, for example, has reviewed Tilley’s fieldwork in south Wales and, as well as questioning some of the field observations, urges the need to consider alternative perspectives in interpreting the location of prehistoric monuments. Thus, while monuments may indeed indicate places that were held of particular mythological significance, they may have been sited so as to overlook a particular area or an important routeway. Furthermore, if we are to consider monuments in relation to natural features, these must include not only rivers, hills and rock outcrops, but vanished elements such as sacred trees or groves (Fleming 1999).

Fleming’s critique highlights several of the difficulties inherent in the phenomenological approach. Yet it remains the case that, whatever the shortcomings of method, any attempt to understand a prehistoric monument which fails to consider the landscape setting is omitting one of the most salient characteristics. Here again we must distinguish between the monument, abstracted in a plan or a field report, and the monument as a visible structure, experienced within its surroundings. The holistic and integrated nature of human experience obliges archaeologists to seek to establish the original associations of meaning wherever possible. This is clearly most accessible where monuments can with some confidence be related to well-defined or prominent landscape features (such as rock outcrops, coasts, or offshore islands), and where ethnographic information can be drawn upon to increase the richness and plausibility of a particular interpretation. Thus in northern Europe, Knut Helskog has been able to draw on Saami cosmology to understand the rock-art motifs of coastal Norway (Helskog 1999). Similar cosmologies may underlie the coastal concentration of passage graves in Brittany, or on the Orkney islands.

Several Continen...