eBook - ePub

Software Development

An Open Source Approach

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

To understand the principles and practice of software development, there is no better motivator than participating in a software project with real-world value and a life beyond the academic arena. Software Development: An Open Source Approach immerses students directly into an agile free and open source software (FOSS) development process. It focus

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Overview and Motivation

“Change your opinions, keep your principles; Change your leaves, keep intact your roots.”

—Victor Hugo

This chapter discusses the short history and current scope of computer software and its development. We focus on the origins and evolution of “free and open source software” (often called FOSS), identifying its distinctions from “proprietary software,” which is generally neither free nor open source.

You will learn that these two genres of software have different sources of support, goals, development methodologies, and outcomes. Studying the methodologies and goals that drive the development of free and open source software is the main focus of this book.

1.1 Software

Software is a fundamental element of computing. It provides the functionality that allows computers and networks to serve the needs of organizations and individuals. Software and computers are intertwined in a kind of deadly embrace; neither one can survive unless the other one thrives.

In today’s developed world, software is everywhere. It enables individuals to use an Android phone, Google the Web, communicate with friends, type essays, manage bank accounts, pay taxes, navigate an automobile to an unfamiliar destination, make flight reservations, listen to music, and view photos and videos on their computers. And that’s just how individuals use software.

Organizations also rely on software. Small and large businesses, non-profit organizations, banks, government agencies and contractors, universities, research laboratories, and countless other institutions use software to help manage their day-to-day activities.

Without a Web presence for marketing their products and services, most enterprises would not survive in today’s world. Organizations also use software to manage their various internal activities—financial accounting, production lines, employee and volunteer recruitment, fundraising, inventory control, payroll, and so on.

Software is also dynamic. Every viable software product changes with each new generation of computers, operating systems, and modes of access to worldwide information. If we were to read a definition published in, say, 1965 about the nature of software, we would probably not recognize that definition.1

1.1.1 Types of Software

In the last four decades, we have witnessed such a revolution of computing and networking that it now influences nearly all areas of business, scientific, and personal life. This revolution has dramatically changed how individuals and organizations function, and it has also dramatically enlarged the scope and definition of “software” as it is understood today.

Software development methodologies and distribution strategies have also undergone a significant transformation. This transformation has produced the following distinctions:

Bundled vs Unbundled Software Some software items are bundled together in an inseparable way, requiring the client to purchase all of the items at once, even when only one is desired. Further, some software is bundled together with a “native” hardware platform and operating system, making it very difficult for a client to choose among alternatives once the platform has been determined. For example, Microsoft bundles its word processing, spreadsheet, and presentation software into a single package called “Office.” To use Microsoft’s word processor, called “Word,” one must purchase the complete “Office” bundle, whether the other two products are needed or not.

Client “lock-in” is said to occur when such bundling forces the client to stay with a particular software suite or manufacturer even though better alternatives may be available on the market. Monopolistic behavior has been a frequent activity of some software developers, in their appetite for gaining control of entire software markets by eliminating the competition.

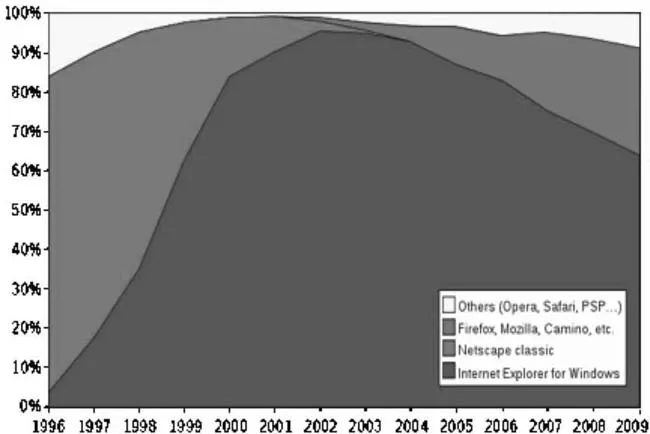

For example, Microsoft, which controlled over 90% of the desktop computer market in 1998, began to bundle its Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operating system. Netscape and other browser developers complained that this practice was monopolistic. The U.S. government opened an antitrust investigation, which led to an indictment and a ruling against Microsoft [wp-h]. The ruling was eventually overturned on appeal, but the case’s findings of fact—that Microsoft had engaged in monopolistic practices—were allowed to stand and led to an eventual settlement. Nevertheless, the net effect of this action was that Microsoft had effectively taken over the browser market from Netscape, and went on to capture over 90% of that market at its peak in 2001 (see Figure 1.1) [wp-a].

Client “lock-in” is said to occur when such bundling forces the client to stay with a particular software suite or manufacturer even though better alternatives may be available on the market. Monopolistic behavior has been a frequent activity of some software developers, in their appetite for gaining control of entire software markets by eliminating the competition.

For example, Microsoft, which controlled over 90% of the desktop computer market in 1998, began to bundle its Internet Explorer browser with its Windows operating system. Netscape and other browser developers complained that this practice was monopolistic. The U.S. government opened an antitrust investigation, which led to an indictment and a ruling against Microsoft [wp-h]. The ruling was eventually overturned on appeal, but the case’s findings of fact—that Microsoft had engaged in monopolistic practices—were allowed to stand and led to an eventual settlement. Nevertheless, the net effect of this action was that Microsoft had effectively taken over the browser market from Netscape, and went on to capture over 90% of that market at its peak in 2001 (see Figure 1.1) [wp-a].

FIGURE 1.1: Market shares during the “Browser Wars”

(source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Browser_wars).

Mass-Marketed vs Custom Software Most commercial software is developed for the mass market, using a “one size fits all” strategy. With this strategy, the price of an individual copy can be kept small, while the degree to which the software matches with the client’s actual needs varies. Often, mass-marketed software contains many more features than any one individual needs or wants, and the quality of such software is minimally satisfactory in relation to its price.

Custom software is tailored to fit the needs of a particular client, usually a large client with very specialized needs. Such software is typically more expensive to develop, and so the client must either cost-justify its development or seek less expensive alternatives. Examples of custom software include that which underlies the Federal Air Traffic Control System or the operation of a particular bank’s ATM system. The history of these two software development efforts is quite different – the former was a colossal failure and the latter is a resounding success.

Custom software is tailored to fit the needs of a particular client, usually a large client with very specialized needs. Such software is typically more expensive to develop, and so the client must either cost-justify its development or seek less expensive alternatives. Examples of custom software include that which underlies the Federal Air Traffic Control System or the operation of a particular bank’s ATM system. The history of these two software development efforts is quite different – the former was a colossal failure and the latter is a resounding success.

Proprietary vs Open Source Software Proprietary software is that which is licensed and distributed as a binary executable program to individual and corporate clients. The source code is the private property of the developer. A proprietary software license typically prevents the user from installing the software on more than one computer. It also prevents the user from copying the software, modifying it, or sharing it with associates and friends.

Free and open source software (FOSS) is that which is licensed and distributed along with its underlying source code. Most significantly, “free” means that clients are free to use the software on any computer, to modify the software, and to share the software with associates and friends. Because of this freedom, FOSS is accessible in markets where proprietary software has no interest and little leverage—non-profit organizations, developing countries, and individuals who are either unwilling or unable to pay the (sometimes steep) cost of proprietary software.

Free and open source software (FOSS) is that which is licensed and distributed along with its underlying source code. Most significantly, “free” means that clients are free to use the software on any computer, to modify the software, and to share the software with associates and friends. Because of this freedom, FOSS is accessible in markets where proprietary software has no interest and little leverage—non-profit organizations, developing countries, and individuals who are either unwilling or unable to pay the (sometimes steep) cost of proprietary software.

From the 1970s to the mid-1980s, nearly all application software development was proprietary.2 Proprietary sofware is typically developed and maintained by an in-house programming staff of a large organization or by a software vendor targeting a specific mass market.

For example, Microsoft Word was developed to meet the needs of the word processing market, and the “Office” bundle (Word, Excel, and PowerPoint) currently sells for about $400 per copy (students may purchase Office for $150). Office is licensed under the “Microsoft Software License Terms: 2007 Microsoft Office System Desktop Application Software.” This license spells out, in 165,181 bytes, all the do’s and (mostly) don’ts for clients who purchase the right to install and use a single copy of the Office software on a single computer.

The open source analog for Word is called “Writer” and is available inside the “OpenOffice” bundle, developed by OpenOffice.org. OpenOffice is available for free download, use, and adaptation by any individual or organization (see openoffice.org). It can be run on Windows, Linux, and Macintosh platforms. OpenOffice is distributed under an open source license called the “GNU LGPL,”3 which describes in 8,518 bytes the rights of clients who download and freely use, copy, modify, and redistribute this software.

During the last two decades, open source software development has emerged to become a major player in the software industry. This momentum is spurred by many forces, including the world’s need for affordable computing, new developments in software methodology, and the increasing sense of public ownership of the internet and its resources. It is now estimated that open source software is in use on over 20% of all computers worldwide (see [Sal08] p. 161), and this share is steadily growing.

1.1.2 The Changing Landscape

The worldwide growth of the Internet, especially the opportunity it provides for free collaboration, is a primary enabler for the recent emergence of the open source software movement.

Three other major factors have also helped drive this emergence: a persistently high failure rate among proprietary software projects, a high level of frustration among proprietary software customers, and the business model that drives the proprietary software development process itself. These factors are discussed below.

1.1.2.1 Project Failure Rate

Given our personal experience with today’s successful proprietary software products, we might be lulled into the belief that a proprietary software development project usually results in a successful product. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A major reason for the emergence of the open source movement is the high rate of failure in proprietary software development over the last four decades. This period is littered with major project failures, such as the 1994 failure of IBM to deliver a working air traffic control system to the FAA after collecting billions of taxpayer dollars over a six-year development period (see www.baselinemag.com/c/a/Projects-Processes/The-Ugly-History-of-Tool-Development-at-the-FAA/).

A more recent failure is Microsoft’s “Windows Vista” operating system, which at this writing had captured only 21% of the operating system market, compared with a 67% share by “Windows XP,” its aging predecessor (see en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Usage_share_of_desktop_operating_systems).

Mountains of articles have been published about the high frequency of software project failures throughout the last several decades. The 2009 CHAOS Report [Groa] cites software failure rates at the highest level in a decade: 44% of all software projects failed to be delivered on time, on budget, or with full functionality. An additional 24% were cancelled prior to completion. This leaves only 32% of all software projects that were completed on time, on budget, and with full functionality—a dismal record indeed.

There are many reasons for software project failure, including:

• inadequate definition of the problem to be solved,

• gross underestimation of the task to be performed,

• inadequate management support or funding,

• overly ambitious development schedule,

• poor design,

• inadequate programmer deployment, and/or

• poor market analysis.

However, improper choice and deployment of an effective development methodology is almost always at the center of a failed software project.

1.1.2.2 Customer Frustration

Added to this history of failure is the current climate of users’ frustration with the proprietary software that they have purchased (or that their employer requires them to use). Often an organization’s needs are not well met by these proprietary products, but the cost of conversion to a better alternative (along with vendor lock-in) prevents them from making changes.

Since proprietary software licensing is so restrictive, it is virtually impossible for organizations to modify or share the software with other organizations or individuals. In addition, an organization cannot hire a programmer to fix a bug or add useful features to proprietary software. The organization is completely dependent on the vendor for this service, and the vendor may or may not be responsive.

This type of vendor lock-in often even hinders the customer’s ability to change its underlying hardware or operating system platform. Lock-in also forces the use of proprietary data formats, which makes it more difficult for an organization to export and use its own data in a different software application. An organization that has invested heavily in a proprietary product is often unable to justify changing to a new product because of the substantial data conversion and training costs involved in moving to a new platform.

1.1.2.3 Business Model

Over the years, we have be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Overview and Motivation

- Chapter 2 Working with a Project Team

- Chapter 3 Using Project Tools

- Chapter 4 Software Architecture

- Chapter 5 Working with Code

- Chapter 6 Developing the Domain Classes

- Chapter 7 Developing the Database Modules

- Chapter 8 Developing the User Interface

- Chapter 9 User Support

- Chapter 10 Project Governance

- Chapter 11 New Project Conception

- Appendix A Details of the Case Study

- Appendix B New Features for an Existing Code Base

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Software Development by Allen Tucker,Ralph Morelli,Chamindra de Silva in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Programming Algorithms. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.