- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Airline Business in the 21st Century

About this book

This book focuses on the major issues that will affect the airline industry in this new millennium. It tells of an industry working on low margins and of cut-throat competition resulting from 'open skies'. Among the issues discussed are:

* the low-cost airline

* the impact of electronic commerce

* the debate on global airline alliances

* privatizing state-owned airlines

* the creation of a Trans Atlantic Common Aviation area

Most importantly, the book carefully analyzes the strategies that are needed for airlines to succeed in the twenty-first century. This is essential reading for anyone interested in aviation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Airline Business in the 21st Century by Rigas Doganis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Recent trends and future prospects

1.1 The good, the bad and the indifferent

For the then Chairman of Air France, 1993 was an unhappy time. Every evening, as he left his office to go home, his airline had lost another US$4 million! This went on, day in day out, for a year or so. Of course, it was not quite like that. But by the end of that financial year, his airline had lost almost US$1.5 billion. Such figures graphically illustrate the depth of the crisis faced by the world’s airlines in the early 1990s. This was a bad time for the airline business.

While the years 1987 to 1989 had been highly profitable, in the period 1990–93 the airline industry faced the worst crisis it had ever known. The crisis started early in 1990 as fuel prices began to rise in real terms while a worsening economic climate in several countries, notably the USA and Britain, began to depress demand in certain markets. The invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990 and the short war that followed in January 1991 turned crisis into disaster for many airlines. Eastern Airlines in the United States and the British airline Air Europe collapsed early in 1991 while Pan American and several smaller airlines such as Midway in the United States and TEA in Belgium had gone by the end of the year. The end of the Gulf War early in 1991 did not lead to any improvement in airline fortunes, since the underlying problem was the slowdown in several key economies, not the war. In many markets, such as the North Atlantic, liberalisation combined with inadequate traffic growth was resulting in overcapacity and falling yields as airlines fought for market share. Financial results in 1992 were worse than in 1991, and 1993 was little better. Of the world’s twenty largest airlines, only British Airways, Cathay, SIA (Singapore Airlines) and Swissair made a net surplus in each of the three years 1991 to 1993. It was the North American carriers that posted the largest losses in this period. Conversely several Asian airlines continued to operate profitably.

A number of airlines required massive injections of capital to survive through the early 1990s, particularly Europe’s state-owned airlines such as Air France. Those from member states of the European Union received US$10.4 billion in ‘state aid’ in the period up to 1995. This was government funding provided after approval by the European Commission. Later in 1997 Alitalia was given $1.7 billion of state aid. In addition several airlines received government funds of various kinds totalling nearly $1.3 billion but not categorised by the European Commission as ‘state aid’. Even privatised European airlines received capital injections from their shareholders through rights issues during this period (Chapter 8, Table 8.4). Outside Europe most state-owned airlines needed direct or indirect government subsidies to keep going.

After 1994 as the cost-cutting measures launched in the crisis years began to have an impact and as demand growth began to pick up, many airlines returned to profit. This improving trend continued in 1995, 1996 and 1997. Of the larger carriers two groups, the major Japanese carriers and the state-owned airlines of southern Europe, performed less well than their counterparts and several, such as Japan Airlines and Alitalia, continued to make losses. Overall, however, these were boom years for the airline industry. In absolute terms 1998 was the most profitable year ever.

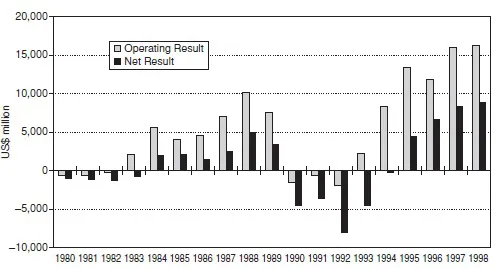

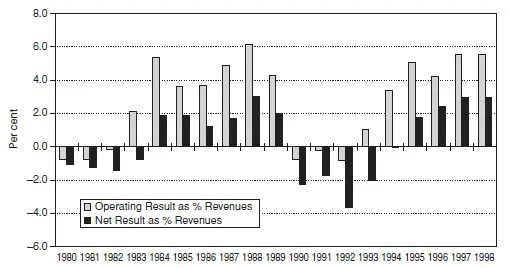

The significant improvements in airline profit levels in the mid-1990s reflected the cyclical pattern that appears to characterise the airline industry (Figure 1.1). Four to six years of reasonable profits are followed by three or four years of marginal profits or losses. While the overall profits in the period 1994–97 appear to be higher than those of the corresponding period in the 1980s, the profit margins (i.e. profits as a percentage of revenues) are no better (Figure 1.2). However, even in the good years profit margins are low. The net profits, after interest and tax, rarely achieve even 2 per cent of revenues. In 1998, the best year in absolute terms, the net operating result was only 3 per cent. Clearly, the airline industry is not very profitable compared to other industries. Of course some airlines, as previously mentioned, performed much better than the average. But even they rarely achieved a 10 per cent operating margin.

Despite the overall improvement in airline financial performance after 1994, airlines had become increasingly indebted as they borrowed heavily to finance their losses or to pay for aircraft ordered in the good years of the late 1980s. As a result, during the 1990s interest payments rose alarmingly. Many airlines, while making an operating surplus, were pushed into the red as a result of their large interest payments. The total interest payments that had to be paid each year rose dramatically during this period and were an indication of the industry’s growing indebtedness. Annual interest payments for the international operations of IATA’s member airlines doubled from $1.8 billion in 1988 to $3.6 billion in 1992 and have remained at over $3 billion per annum since then. This is so despite the huge write-off of debts among many state-owned airlines in Europe who used their ‘state aid’ primarily to cancel some of their accumulated debts.

As the new millennium approached the airline industry was faced with conflicting signals. Early in 1998 the United States airlines announced that 1997 had been their best year ever, with net profits reaching US$6 billion. Yet at the same time it was apparent that many Asian carriers were in dire straits. The economic crisis and meltdown that began to affect East Asia in the second half of 1997 hit Asian carriers hard. The economic downturn choked off the anticipated traffic growth. On many intra-Asian routes passenger and cargo traffic grew less rapidly than anticipated or even declined. At the same time, the dramatic devaluation of many airlines’ home currencies significantly reduced the value of their foreign revenues while at the same time increasing those costs denominated in hard currencies. Fuel costs, interest charges and debt repayments rose sharply. Foreign currency denominated debts also rose.

Figure 1.1 ICAO World airline financial results, 1980 to 1998 (US$).

Figure 1.2 ICAO World airline financial results, 1980 to 1998 (as a percentage of revenues).

By mid-1998 many East Asian airlines were posting large losses for the financial year 1997. Japan Airlines led the way with a net loss of US$513 million. Others’ losses were not as high, but were still substantial. Asiana, the Korean airline, lost $425 million, Korean Airlines $424 million and Philippine Airlines $253 million. Only Thai Airways, Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines and some of the Chinese airlines bucked the trend, though the first two had significantly lower profits than in 1996.

For the East Asian airlines 1998 was even worse than 1997. While Japan Airlines and Korean managed to move from loss into profit, most carriers’ financial performance deteriorated. Cathay Pacific nosedived into loss, its first ever. Philippine Airlines virtually collapsed in July 1998 after a disastrous pilots’ strike. A very slimmed-down operation had to be resurrected twice through capital injections and financial restructuring in the months that followed. In Indonesia two large domestic airlines ceased operations while Garuda, the national carrier, teetered on the verge of collapse but kept flying. In 1999 both Philippine Airlines and Garuda brought in foreign managers to try and turn them round.

European and North American airlines were affected by the downturn in traffic on their routes to East Asia. In some cases, this forced them to close routes or switch some new capacity to other markets. Nevertheless, for these airlines, 1998 was as good or better in terms of profitability than 1997 had been. Results were helped by the fact that aviation fuel prices had dropped by nearly a third during 1998. Only a handful posted lower profits. British Airways, KLM and US Airways were among them. The first warning signs were appearing. Those American and European airlines which had performed so well in 1997 could see clouds gathering on the horizon. Yet they could still feel the pain of the deep economic crises they had suffered in the early 1990s.

The situation began to deteriorate further in 1999. Though in February 2000 the ten largest United States airlines as a group posted marginally higher net profits for 1999 than for the previous year, this was achieved through wide-ranging asset disposal. British Airways, which had maintained profitability throughout the crisis years of the early 1990s, was projecting losses for 1999. In fact, as the new millennium approached, many airline chairmen were issuing profit warnings.

Yet the major world economies were doing reasonably well and the forecasts were good. Even those Asian tiger economies which had gone into freefall in 1997, and Japan, where growth had slowed down, were on an upswing by the end of 1999. What were the causes of so much concern? Two major factors were affecting profits. First, overcapacity in many markets, especially on international routes as airlines fought for market share, was pushing down average yields. This trend was exacerbated in Europe and the United States by the pricing strategies of low-cost, no frills carriers. While yields were going down costs were starting to climb in real terms. During 1999 the OPEC countries had imposed production quotas so as to push up the price of oil. They succeeded in this. Prices for Brent crude oil rose from $10.28 per barrel in February 1999 to $28.14 a year later. Prices for jet fuel followed the same trend. Airlines which had not hedged their future fuel purchases were badly hit. The strengthening of the US dollar against many currencies, including the Euro, made matters worse.

Falling yields and rising costs suggests that the worsening climate for airlines, especially international airlines early in the new millennium appeared to be supply-led. This contrasts with the much deeper crisis in the early 1990s, which was demand-led in that it was caused primarily by a sharp drop in demand growth as major industrialised economies slowed down. The conundrum which had to be faced was whether the supply side problems would be sufficiently serious and unmanageable to bring about a major cyclical downturn in the airline industry some time in the period 2000 to 2003. History, as indicated in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, suggested that a downturn was due, or would airline managements take corrective action in time?

1.2 Past trends

To gain an insight into the airline industry’s prospects and problems one must appreciate the market environment within which it has been operating and which has affected its development in recent years.

The most significant trend since the early 1980s has been the gradual liberalisation of international air transport. This has had profound effects both on market structure and on operating patterns. On the transatlantic and transpacific routes liberalisation started in the early 1980s as the United States, following domestic deregulation in 1978, began to renegotiate more open and less restrictive bilateral air services agreements (see Chapter 2). In Europe, the first liberal ‘open market’ bilateral was that between the UK and the Netherlands in 1984, which was followed in December 1987 by the first ‘package’ of liberalisation measures introduced by the European Community. In many parts of the world, governments influenced by the tide of liberalisation allowed the emergence of new domestic and/or international airlines able to compete directly with their established national carriers. Thus, in Japan, the domestic airline All Nippon Airways was allowed to operate on international routes for the first time in 1986. Elsewhere many new airlines emerged, EVA Air in Taiwan, Asiana in South Korea, Virgin Atlantic and Ryanair in Europe among them.

In Europe, the process of liberalisation culminated in the so-called ‘third package’ of measures, which came into force on 1 January 1993. These effectively ensured open and unrestricted market access to any routes within the European Union for airlines from any member state while at the same time removing all capacity and virtually all price controls. They also removed the ownership constraints. Henceforward, airlines within an EU member state could be owned by nationals or companies from any of the other member states. (Chapter 3 deals with these developments.) In the mid- to late 1990s liberalisation in Europe facilitated the emergence of a new breed of low-cost low-fare airlines, such as easyJet, Debonair and Air One, which modelled themselves on Southwest in the United States (see Chapter 6).

At the same time, from 1992 onwards, the United States began to sign a series of ‘open skies’ bilateral air services agreements. They too effectively removed most market access or price controls on the air services between the countries concerned. But the ownership constraints remained. Airlines designated by each state had to be ‘substantially owned and effectively controlled’ by nationals of that state. The first ‘open skies’ agreement was with the Netherlands in 1992. Over forty such agreements had been negotiated by the United States by early 2000. (See Chapters 2 and 3 for an analysis of the deregulatory developments.)

This trend towards liberalisation of economic regulations significantly changed market conditions in those parts of the world where such liberalisation took place. In particular, it resulted in the emergence of new airlines on many international air routes. In some cases, these were newly created airlines such as EVA Air; in others they were established carriers entering particular international routes for the first time. Very powerful but hitherto largely domestic United States carriers such as United, Delta, American and Brannif, launched new international operations. They were joined in the early days by new entrant airlines such as People Express, Air Florida and others, though few of these survived for long. United and Delta launched their international networks beyond the Americas by respectively buying out and expanding the transpacific and transatlantic operations of Pan American.

A further consequence of liberalisation was that there was much less control of capacity and frequency on many routes while at the same time there was considerably greater pricing freedom. While published international fares continued to be established through the machinery of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), such agreed fares were frequently and openly flouted.

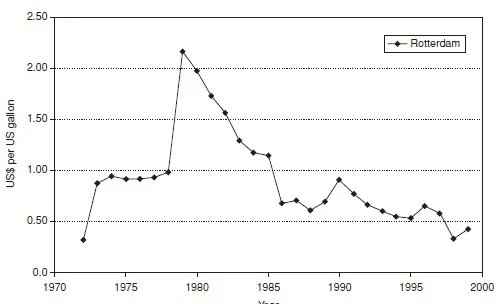

Another key factor which has had a major beneficial impact on the airline industry during the last ten years or so has been the relatively low price of aviation fuel and the general stability of the price level. This contrasts sharply with the high prices experienced in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The price of fuel shot up dramatically on two occasions as a result of crises in the Middle East: first in 1973–74 when it more than doubled in price and in 1979 when again the price doubled. The average price of jet fuel rose from 32 US cents per gallon in 1972 (in 1997 US dollar values) to almost two dollars in 1980 (in 1997 US dollar values) (Figure 1.3 ). Fuel became the major airline cost for a time, representing 30 per cent to 33 per cent of total operating costs. These high fuel prices were one of the major causes of the losses incurred during the cyclical downturn of the early 1980s( Figure 1.1). But from 1981 onwards fuel prices began to decline gradually in real terms and dropped sharply in 1986. The sharp drop experienced in 1986 in turn partly explains the high profits achieved in the years 1986 to 1989.

Figure 1.3 Fuel price trends 1972 to 1999 (Rotterdam spot prices at constant 1992 prices).

What is more significant is that since 1986 the price of aviation fuel has stabilised at a value which in real terms is a little less than double the level prior to the two oil crises. But it is still substantially lower than the prices prevailing during the early 1980s. The price does fluctuate, but around a more or less constant level. Thus, while the 1990 Kuwait crisis and war of 1991 produced a sudden sharp hike in fuel prices, the prices were back close to their pre-crisis levels within a year (Figure 1.3). Again in late 1996 there was a sharp increase, but prices declined during 1997 to earlier levels. In fact, in 1998 jet fuel prices dropped even further to levels not experienced since 1972. Fuel prices did rise appreciably during 1999 and early 2000 as a result of OPEC cutbacks in petroleum output mentioned earlier. Average spot prices for jet fuel rose from around 32 US cents per gallon in February 1999 to almost 77 US cents in February 2000, an increase of 140 per cent or so. Despite this it is clear that fuel prices have tended to become less volatile in the long run because oil production is now much more dispersed geographically than it was in the 1970s. A crisis or shortfall in production in one area can more easily be met by increased production elsewhere. It is significant that low fuel prices prevailed in the late 1990s despite the fact that Iraq, previously the world’s second-largest oil exporter, was no longer able to export oil as a result of a United Nations embargo on Iraqi exports. It is likely that in the medium term the high fuel prices of late 1999 and early 2000 will come down to levels prevailing in the mid-1990s, that is, 50 to 60 US cents per gallon. The decline and stabilisation in the price of aviation fuel means that the cost of fuel during most of the 1990s represented between 12 per cent and 15 per cent of airlines’ total operating costs. Most forecasters predict that during the first decade of the new millennium fuel prices measured in constant values will either continue to be fairly stable, though with some sharp, short-term fluctuations, or at the very worst they may increase in real terms at a low rate of 1 or 2 per cent per annum.

The third trend underlying the development of air transport is that traffic growth rates have been declining. In the decade 1966–77 the world’s air traffic measured in terms of passenger-kilometres grew at an annual rate of 11.6 per cent, effectively doubling every six or seven years. In the following decade up to 1987 annual growth was less but still high at 7.8 per cent. But during the period 1987 to 1997 the traffic growth declined further to around 4...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Recent Trends and Future Prospects

- 2. Towards ‘Open Skies’

- 3. Beyond ‘Open Skies’

- 4. Alliances: A Response to Uncertainty or an Economic Necessity?

- 5. Labour Is the Key

- 6. The Low-Cost Revolution

- 7. [email protected]

- 8. State-Owned Airlines: A Dying Breed or a Suitable Case for Treatment?

- 9. Strategies for the Twenty-First Century

- Appendices

- Bibliography