![]()

CHAPTER 1

“Our Star and a Vision for Us”:

A Midwife's Tale of Social Change and Control, 1931–1966

Because the Guatemalan government wanted to establish biomedicine as the primary health care system, Germana Catú’s (1879 [1889]?–1966) decision to become a midwife in 1931 set her on a collision course with the state. At stake were not only her vocation but also her people's culture, traditions, and authority. The state's attempt to control midwives and further imbue their communities with Western ideologies was in part predicated on a social structure that privileged Ladinos and denigrated Maya. Even though (or perhaps because) Germana Catú overcame these obstacles, defended Mayan epistemologies, culture, and ethnicity, and attracted Ladino doctors and patients to her practice, Kaqchikel men have excluded her from their community's historical discourse. The gendered nature of Kaqchikel oral histories starkly manifests itself in women's vigilant defense and perpetuation of the historical memory of this Catholic lay leader. Elder females preserve histories such as Germana's as a reminder of past female accomplishments and challenges and to guide and inspire their female progeny in their contemporary lives.1 One woman, who was not even alive at the time of Germana's death, asserts, “Germana Catú did excellent work and she was of top character.”2 As an individual, Germana challenged Mayan gender norms and Ladino perceptions of “indios ” (Indians).3 As an historical figure, she deconstructs the sexual division of public and private spheres and the Ladino versus Maya dichotomy. Germana Catú’s tale repositions women not just in history but as history.

Uncovering Germana's history reveals one of the ways Maya resisted government attempts to control, co-opt, and infiltrate their communities. Beginning in the 1930s, health officials sought to impose biomedicine on midwifery. Ostensibly the goal was to improve and mandate public health. However, this outreach was also one facet of the state's attempt to form a more homogeneous, united national society by forcing Maya to acculturate to Ladino norms. In contrast to the state's efforts and hopes, Germana, like most of her contemporaries, learned her trade through autochthonous gnosis and experience, not government-sponsored training programs. She upheld Mayan medicine against the state's attempts to discredit it. And in the process, she inverted the paradigm of Ladino and state domination.

Germana's medical talents compelled some Ladinos to respect her and, by association, Mayan epistemologies. When Ladino doctors came to offer training sessions to midwives or care for highland patients, they often sought Germana's counsel. Her story offers a rich understanding of ethnic relations that complicates the portrayal of racist Ladinos and marginalized Maya. Germana served both Maya and Ladinos in her practice, and attempted to develop ways to mitigate ethnic strife. She earned the respect of some Ladinos during her lifetime and the devotion of others after her death (see epilogue). Her tale reveals the potential of Maya to influence, teach, and even safeguard Ladinos, who in turn, at times, respected, even revered, their indigenous compatriots. These interactions and the potential for change they augur deconstruct notions of ethnic animosity and showcase symbiotic ethnic relations. Against a backdrop of the harsh impoverished conditions under which most Mayan women lived, Germana Catú is an exceptional figure, which is one reason why she is remembered. Read in this context, her story illustrates a contentious and injurious historical reality that runs counter to the ethnic harmony and gender equality she sought to model.

Germana's case elucidates a reluctance on the part of Kaqchikel men to ascribe historical importance to women or to glorify outspoken, successful, powerful female figures. Her absence from men's oral histories cannot be explained as an effort to favor communal history at the expense of individuals’ achievements and plights; oral histories laud local male leaders and icons such as Nemesio Matzer and Rafael Alvarez Ovalle (1858–1946). Nor can this oversight be attributed solely to sexist ideology; Mayan men insist women's skills, contributions, and very existence are imperative to the survival of their communities. Since most of their work entailed interactions only with women (except during childbirth when the husband was often the only male present) in the privacy of the tuj (sweat bath), midwives operated in an almost exclusively female world.4 In part because men experienced a certain anxiety about the “mysteries” of female sexuality and the nebulous borders within which midwives moved, they left the transmission of information about this role to women.5 Even though midwives were highly recognized figures who were the focal points of social relations in Mayan communities, only women acknowledge them as protagonists in their oral histories. Yet as a lay leader in the Catholic church—a role traditionally reserved for men—Germana was problematic for Kaqchikel men in another way as well: She assumed an assertive, extraverted role when women were to be reticent in public.

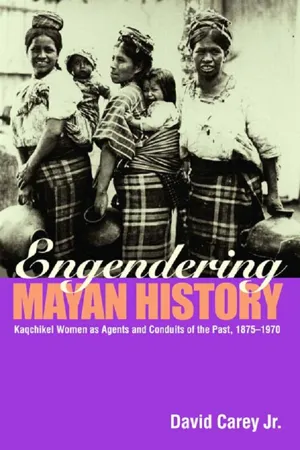

Figure 3 Portrait of Germana Catú, ca. 1972. Painted by her grandson, Salvador Cúmez, after her death. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the artist.)

Her tale encourages us to rethink the gendered construction of domestic and public spheres in the context of a systematic analysis of social relations in Mayan communities and Guatemala.6 Germana's vocation demanded that she have unrestrained mobility in the public and private world. Although men assumed a significantly greater external role than women, women's lives were not devoid of public activity. As merchants, vendors, washerwomen, and in some of their daily chores such as fetching water or firewood, women moved in public circles and expressed their opinions. In ruminating on his youth in the 1930s, one Guatemalan writer describes Mayan market women as “a vocal and militant faction in the affairs of the [Guatemala] city.”7 In some public arenas, Mayan women were outspoken and forceful, though generally as a group, not as individuals. As a midwife, Germana had greater liberties than other women because her work required that she be on call twenty-four hours a day. Consequently, it was not unusual for her to be on the streets during late evening or early morning hours, when most others—men and women—would be in their homes. Since most midwives were widows, they already enjoyed more independence than younger single or married women did, but the nature of their profession further unfettered them from restrictions that customarily curtailed women's—even widows’—options and activities. Because they operated outside male power structures and systems of knowledge, men often looked upon midwives with suspicion,8 but their freedoms did not openly challenge Mayan communities’ understandings of gender relations and roles. Midwives were recognized as a necessary, if problematic exception.

While Germana's involvement with midwifery did not fit neatly into community gender norms, her efforts to bring Catholicism to monolingual Kaqchikel speakers blatantly blurred the lines of women's level of public involvement and, more importantly, modeled alternative gender rights and obligations. Catholic Action, which sought to extirpate non-Catholic influences from local religious practices and regain control of local churches from traditional forces, such as cofradías, was a new element emerging in Latin American Catholicism in the 1930s and 1940s. Even though it did not espouse a feminist agenda (it was still firmly grounded in the patriarchy of the Catholic Church), by attacking cofradías, Catholic Action created spaces for women to emerge as lay leaders and become more vested in the church. Germana took advantage of this opportunity to become a spokesperson and prayer leader. By abjuring the traditional expectation that women refrain from assuming leadership positions in public affairs, she threatened men's positionality. In addition, since Catholic Action proved to be a divisive (and at times violent) element in many Mayan communities and was in part responsible for a riot in Germana's hometown of Comalapa in 1967 (see Chapter 4), some elders (especially former and current cofrades ) may have downplayed her role in the community because of her association with what they perceived to be an inimical intrusion. Mayan women were not passive or insignificant contributors to their communities, but men did not envision them as leaders with their interests at heart. Germana's disruption of both gender and ethnic politics alienated her from Mayan men who subsequently used their oral histories to cloak her transgressions.

In addition to these affronts against Mayan patriarchal structures, Germana's success as a single mother who provided for her family (and community) took exception to the notion of the male breadwinner. What further increased male anxieties was that Germana did not simply survive without the aid of a man; she thrived. When Kaqchikel men couched gender difference in a language of community heroics or tribulations and silent women, how could they reconcile their stories with Germana's prowess? Her talents and skills were essential for the community and her example intimates the fluidity of gender differences among Maya. Germana was not unique in this sense, nor were these circumstances reserved for midwives. Although many single Mayan women suffered from poverty and oppression, oral histories and archival documents indicate that some supported themselves and their families well.9 Particularly compared to Ladinas, Mayan women were relatively autonomous in their communities where they could move about freely, inherit land, and secure their own sources of income.10 Yet if their financial and emotional independence was too notorious, it threatened the notion of complementarity—the idea that both men and women were vital to the daily functioning of the family and community.

Ironically, the sexual division of labor that prejudiced women by not compensating them for domestic work also afforded them a degree of independence that men lacked. As anthropologist June Nash points out in her study of Amatenango, a Mayan town in Mexico, “Women can live without men in the household economy of the town, but men cannot live without women. This is because male labor is a market commodity while female labor in household activities is not. A widow can hire a man to work her fields, but a man cannot hire a cook. If he is widowed, he must remarry, move into his mother's house, find a wife for a grown son, or find an unattached female relative to live with him.”11 Unlike men, women were indispensable and largely self-sufficient. Anthropologist Carol Smith underscores the significance of this point for women's agency: “Because of her economic autonomy and value, a Maya woman who was abandoned or who wished to repudiate her marriage could return home, remarry, or live independently with her children.”12 While men dominated local politics, women had more flexibility than men in the economic and social spheres of their communities. Even though these liberties did not necessarily translate into material power, by strengthening Mayan women's self-determination, they made clear that women were not dependent on men; the obverse of which was not established so easily. Germana's tale and those of countless other independent Mayan women illuminate the degree to which men depended on their roles as keepers of the past—as official storytellers—to continually reinvent and uphold a history of male power and public importance at the very moment when these positions were most contested, both from within as women assumed more authority and autonomy and from outside as the Catholic church, state, Ladinos, coffee economy, and other social, economic, and political forces undermined “traditional” values, customs, beliefs, and gender norms. Gender difference became most exaggerated when it was most threatened.13

Mayan Midwifery: Respect and Alienation

Almost invariably Mayan women called upon midwives (k'exelona’ ) to assist them in prenatal, birthing, and postpartum care.14 Women were the warriors who brought new life into the world and midwives facilitated this process. Because of its European and indigenous influences midwifery is syncretic, but by the twentieth century most Guatemalans associated it more with the latter than the former.15 Prior to the 1960s, most Mayan midwives did not partake in biomedical training. Their knowledge and skills, which they guarded as trade secrets, came from their ethnic female heritage. In Mayan culture, midwifery was more vocation than profession. Baby girls born on auspicious days were fated to become midwives and, as they grew older, they experienced signs—dreams, sickness, susto (fright)—that intimated their future role.16 Many midwives claimed they were visited by supernatural spirits who convinced them of and instructed them on their calling. Often a diviner helped them to interpret the signs and understand their destiny. Those who ignored or denied their calling often only conceded after a traumatic event. According to some Maya, women became ill and in extreme cases died if they refused to fulfill their vocation. Not all Mayan women claimed a spiritual calling, however; in some cases women simply assumed the position out of desire, interest, or financial need. In any case, many aspiring midwives learned through apprenticeship. Except for a few communities, traditionally midwives began to practice after their own child-bearing years had passed.17

Like other ritual specialists, both female and male, because they were not regarded as ordinary people, midwives were afforded significant flexibility in Mayan society particularly in regard to gender constraints.18 Most public female occupations, such as market vendors or laundresses, were a natural extension of the sexual division of labor and reinforced complementary gender roles in Mayan communities. But midwifery was supplementary, not complementary, to these roles. Midwives had to be free to move about t...