- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

City Worlds

About this book

For the first time in history, half of the worlds population is living in mega-cities. Never before have we confronted such a geography of the worlds people.

Analysing cities through spatial understanding, City Worlds explores how different worlds within the city are brought into close proximity. The authors outline new ways to address the ambiguities of cities: their promise and potential, their problems and threats.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

What is a city?

by Steve Pile

1 Introduction

1.1 Images of the city

1.2 So, what is a city?

2 From nature to metropolis (and back again)

2.1 Chi-goug before Chicago: land and nature

2.2 The making of Chicago: from mud to movement

2.3 Chicago’s nature: the city’s footprint on the face of the Earth

2.4 The ends of Chicago

2.5 Cosmopolitan Chicago

3 The intensity of city life: size, density and heterogeneity

3.1 The number of people

3.2 The density of settlement

3.3 The heterogeneity of cities

4 Conclusion

References

1

Introduction

1.1

IMAGES OF THE CITY

It is easy to ask the question ‘what is a city?’, but—as you might have already anticipated—less easy to answer it. Let us think about images of the city to see why this might be so. Tour operators regularly advertise holidays to cities, where you can revel in the entertainments and sights that they have to offer. Meanwhile, other holiday advertisements proclaim the benefits of leaving the city and getting away from it all. It is not just holidaymakers and the tourist industry that have some sense of what cities are like. Commonly, people will talk of going to the city to get this or that; or they will say that they come from the city, whether because it was their birthplace or where they live. Airlines seek to move high-flying executives between cities: to make contacts, to build up business. Others, meanwhile, are down and out in the city. Moreover, governments tend to locate the major institutions of state in capital cities—some countries even build new cities for the purpose.

In people’s imaginations, there seems to be a clear idea of what the city is—its opportunities, its benefits and its dangers. However, these images of the city are very different: holidaymakers, business managers, city-dwellers, government officials, all have subtly different images of what the city is like, what the city offers them and what they want to do in cities. So, people might have very definite answers when asked what a city is: it is there for pleasure and fun, for cultural events, for business and profit, for home and work, for administration and government, and so on. But, if we want to understand what the city is, then we will have to think about what we learn when these images are put side by side.

ACTIVITY 1.1 Before reading on, reflect for a moment on the images that you have of a city. Make a list of the kinds of images that are springing to your mind. Next, make a separate list of the kinds of things that can only be found in cities. •

My list of urban features began with physical features such as houses, housing estates, streets, shops, hotels, hospitals, museums, traffic, libraries, cathedrals, soup-kitchens, restaurants, and so on —and so on, so I stopped writing after a while. On the other hand, the number of things that can only be found in cities appears to be much smaller: I thought of skyscrapers, underground railways, street lighting (maybe), and not much else. We can see quite quickly that many features of the city can be found outside the city. There are housing estates and hospitals in rural areas, as well as shops and museums, but these tend to be smaller in scale than their equivalents in the city. Maybe what is distinctive about cities is, in essence, a question of size. Is what a city is determined by the scale, say, of its office-blocks or of its housing estates? In part. But a small village with a huge museum or hospital or even a large housing estate would not be a city. Cities have something more than simply ‘largeness’. Sure, cities are big, but their size is related to the way in which they combine most—if not all— of the features on our lists.

If cities are a combination of many features, then this leads to another question: does the city have to have a particular blend of elements to be a city? Yes and no. Very few cities have exactly the same mixture of things. Let us take one example: the skyscraper. A city does not have to have skyscraper to be a city, but skyscrapers are only found in cities. So, the skyscraper is a city feature, but not a feature of all cities. The list of things we find in cities does not appear to add up to what a city is. Maybe there is something more in this question about whether cities combine elements in distinctive ways.

Some time ago, the urban geographer Brian Robson asked himself a similar question about what the urban environment is like. His answer was this:

The urban environment is a deceptively simple term. It conjures up images of crowded Oxford Street (in London) thronged with shoppers, the haunting engravings of Gustave Doré with their pictures of slum life under the railways arches of Victorian London, the pyramid skyscrapers on the skyline of New York, the endless similar, and similarly evocative, images. What it is that we are evoking in such images however, is very difficult to specify with any precision. We tend to conflate the physical and the human aspects together and, while we can say with some confidence what we mean by ‘urban’ in physical terms, it is much more difficult to spell out its social significance.

(Robson, 1975, p.184)

(Robson, 1975, p.184)

In Robson’s view, the city is more than a collection (or combination) of images, but something that has social significance. This suggests that we need to think about the social significance of the items on our list of city features. Certainly, in Robson’s images of the city, there are less tangible aspects such as (over)crowding, shopping and slum life, involving destitution, sickness and hopelessness. You might have noted down similar features on your list of images of the city. For many, it is the intangible qualities of city life that makes it distinctive, such as luxury and poverty, amenity and pollution, tradition and innovation, drudgery and novelty, order and disorder, thrills and spills, volatility and conflict, difference and indifference, public services and welfare provision, individual freedom and dependency on others. Clearly, some of these traits seem to be at odds with others: how can the city contain both order and conflict, freedom and dependency? Perhaps what cities are about is the attempt to deal with (or make the best of) these tensions.

Even it this is right, experiences of the city will differ from person to person as well as from group to group. Indeed, they will vary depending on the part of the city in which the person or group is located. Of course, people’s feelings are not confined to cities: farm work can be every bit as monotonous and routine as factory work, country pursuits just as thrilling as the city’s excitements; loneliness and neighbourliness, wealth and poverty are possible in cities and villages alike. However, the city tends to exaggerate such relationships, if only by bringing them into close proximity. And perhaps this makes matters worse (or better). Once more, what is distinctive about urban experiences might be a question of degree. From this perspective, city life is distinctive because its scale is larger and activities more intense than anywhere else. When we look back over these images, we find that we have raised similar questions about what a city is. The city contains many features and experiences, but simply cataloguing these has not proved enough to define the specific qualities of the city. That is, there is something distinctive about

- the scale and intensity of urban life, and

- the combination of urban elements.

However, we have also found that it is also necessary to consider

- the social significance of the city.

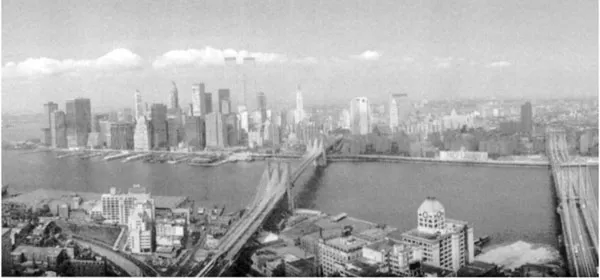

Perhaps we can begin to specify what the city is by taking somewhere we can agree to be a city? Let us consider this image of the skyline of Manhattan Island in New York, USA.

FIGURE 1.1 Skyline of Manhattan, showing the twin towers of the World Trade Center

This city skyline is one of the most famous in the world. Perhaps because few Hollywood filmmakers can resist using it as a backdrop to the action: as the heroine clings by her fingernails to the upper reaches of the Statue of Liberty; as the hero chases the bad guys in a speed-boat towards the towering metropolis; as King Kong meets his doom, atop the Empire State Building. There is something about the skyline which itself evokes action, which evokes something of the action of cities themselves. Urban theorists, too, have also been awed by the sight of Manhattan’s skyscraping buildings. For example, Kevin Lynch describes Manhattan like this:

The image of the Manhattan skyline may stand for vitality, power, decadence, mystery, congestion, greatness, or what you will, but in each case that sharp picture crystallizes and reinforces the meaning.

(Lynch, 1960, pp.8–9)

(Lynch, 1960, pp.8–9)

About a quarter of a century later the French social theorist, Michel de Certeau, would describe the scene this way:

Seeing Manhattan from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center. Beneath the haze stirred up by the winds, the urban island, a sea in the middle of the sea, lifts up the skyscrapers over Wall Street, sinks down in Greenwich, then rises again to the crests of Midtown, quietly passes over Central Park and finally undulates off into the distance beyond Harlem. A wave of verticals. Its agitation is momentarily arrested by vision. The gigantic mass is immobilized before the eyes. It is transformed into a texturology in which extremes coincide—extremes of ambition and degradation, brutal oppositions of races and styles, contrasts between yesterday’s buildings, already transformed into trash cans, and today’s urban irruptions that block out its space.

(de Certeau, 1984, p.91)

(de Certeau, 1984, p.91)

In each of these statements, the writers are trying to get at the way in which the skyline of Manhattan conveys something of the city’s social significance—but with every word they add, this becomes more elusive. Is New York vital, powerful, decadent, mysterious, congested, great; is it ambitious and degraded, a contrast of ethnicities, styles, yesterdays and todays? It is surely all of these things, and more. For de Certeau, the skyscrapers of New York seem to evoke for him the image of a stormy sea, as the height of the buildings rise and fall, as if driven by a tremendous storm. In these waves, he can see some buildings rising and others falling away. Each building representing a yesterday that enabled it to be built and a today that might tear it to the ground—to replace it with something better, something taller. Behind the buildings are the storms of social processes that build; that tear down; that build again.

In both these descriptions of Manhattan, the authors are also trying to capture something of the intensity of the city. For de Certeau at least, New York is born on the stormy seas of money; the city is built on the circulation and use of capital. Indeed, skyscrapers are very expensive, both to tear down and to build. Invariably, investors have sited their skyscrapers in cities—and, as a result, the city’s image is associated with the vitality, prestige and dynamism of such large scale spending. There might be many reasons for building skyscrapers and for siting them in specific cities (and not others), but ultimately de Certeau is asserting that the city is built on— and is stained by—money (even if it is borrowed!).

It matters, then, how money circulates between and within cities, where money accumulates, where people decide to invest it and how they choose to spend it. Surprisingly, then, today some of the tallest buildings are not in the capital cities of the richer countries of the world— such as New York or London or Paris—but in the seemingly poorer countries, in cities such as Kuala Lumpur (see Figure 1.2). And this is important precisely because it changes the image of KL (as Kuala Lumpur is commonly known): so, by building the Petronas Towers, the city intends to rival New York. But does it?

For de Certeau, the city is much more than the outcome of decisions to spend enormous sums putting up very tall buildings. He refuses to be entirely captivated by the seas of buildings that confront him. Instead he begins to look down from the top of the World Trade Center to the streets, to try to pick out what it is that people are actually doing on the ground. But de Certeau cannot make them out. The city seems immobilized before his eyes. On the streets, however, we can imagine the hustle and bustle; the noise of the yellow cabs hooting and the pollution billowing from their exhausts; the crowds of people waiting patiently at street corners to cross the roads and the people thick on the platforms of the underground. On the streets, people are everywhere: walking, jostling, standing, looking, shouting, begging, shopping, and…doing whatever they’re doing. We can imagine millions of people, all with their own stories to tell; the city contains a world of possibilities (see Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.2 Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur

However, the streets de Certeau cannot quite make out from the rooftop of Manhattan are of a particular kind. The streets of New York might be very different from those elsewhere (see Çelik, Favro and Ingersoll, 1994). Indeed, the images we implicitly draw on when we use the word ‘city’ can stem from a very limited repertoire of cities. Thinking about street life in other cities can tell us more about the kinds of things that go on, partly by showing that the city brings together people, commodities, beliefs, money, and so on, from many different places.

ACTIVITY 1.2 Compare the images of the streets in Figure 1.4. What strikes you as being distinctive about each city? What features crop up in different places? •

In Figure 1.4 (a) and (b) we can see images of Hong Kong and of Chinatown in San Francisco. It is just about possible to tell which is which b...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- City Worlds

- Understanding Cities

- The Open University Course Team

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: What Is A City?

- Chapter 2: Worlds Within Cities

- Chapter 3: Cities In The World

- Chapter 4: On Space And The City

- Reference

- Reading 4A

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access City Worlds by John Allen,Doreen Massey,Steve Pile in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.