1

ORIGINS

Karnak is usually associated in people’s minds with the great city of Thebes when it was the capital of the mighty Egyptian Empire, from Dynasty XVIII onwards. But the history of Karnak goes back long before that period to a time when Thebes itself was no more than a small and relatively obscure provincial township on the east bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt. It is not in fact known when the town itself was founded, but very large quantities of palaeolithic flint tools point to an early occupation of this richly cultivatable area. Certainly by the time of the Old Kingdom, evidence is found of tombs on the West Bank opposite Thebes of some very important officials of Dynasties V and VI, indicating a fairly large and well-established settlement area. Even earlier, in Dynasty IV, a deity personifying the Theban nome is represented standing beside the pharaoh Menkaure in one of the famous triad statue-groups from that king’s mortuary temple at Giza (Reisner 1931: pls 41–2). Such a representation indicates clearly the considerable importance of Thebes at this early stage.

Although a large hoard of predynastic and archaic antiquities was unearthed at Karnak, this does not necessarily mean that there was a temple there as early as Dynasty I. More probably it indicates that these ancient objects were dedicated to Amun in later times in the belief that his origins were to be found in remote antiquity (Daumas 1967: 204). As to when the temple of Karnak was founded, it is far from certain. Without doubt, the god Montu, the local deity, was worshipped at Thebes and had a temple in the vicinity from an extremely early, though unknown, date; but the founding of a temple to Amun at Karnak is even more shrouded in uncertainty. There are some snippets of evidence which, while not amounting to anything very positive in themselves, are nonetheless worthy of consideration.

The most recent, and concrete, piece of evidence is the unearthing at Karnak of an eight-sided sandstone colonnette of Wah-Ankh Intef II of Dynasty XI with an inscription mentioning Amun-Re and followed by the words: ‘he made it as his monument for that god . . .’ (Le Saout and Ma’arouf 1987: 294). This is the first known mention of Amun deriving from Karnak itself; it shows no sign at all of any damage or any recarving of the inscription. This must surely imply a temple, or at the very least a shrine, dedicated to Amun at Karnak, particularly since there is a reference to a ‘house of Amun’ in a tomb at Qurneh dating to the reign of Intef II (Petrie 1909: 17 [8], pl. X). Intef himself left a funerary stela in his pyramid on the West Bank at Thebes on which he had inscribed: ‘I filled his temple with august vases . . . I built their temples, wrought their stairways, restored their gates . . .’ (BAR I: para. 421). Though whether this particular reference was to Amun or Montu – or even both – is the subject of some debate.

More tenuous perhaps, but certainly believed by some scholars, is that the Amun temple was more ancient still. In the Festival Hall complex of Tuthmosis III at Karnak there is a small chamber on the south side, named by its excavators the ‘Chamber of Ancestors’ since it has inscribed on its walls the names of sixty-one kings of former dynasties. The earliest surviving name is that of Snofru (Dynasty IV) – but, intriguingly, there is one which predates Snofru, now sadly destroyed. Since this list appears to be a special selection of names, it is felt that these were probably kings who had endowed and enriched Karnak, and consequently were revered by later rulers. Certain finds in the famous Karnak cache (see p. 231) would seem perhaps to bear this out, although there is no positive proof for the theory. The enormous cache of statues and other temple items, found between 1901 and 1905, was buried beneath the court north of the Seventh Pylon. It contained 751 statues and stelae and 17,000 bronzes: these ranged in date from the very earliest periods of Egyptian history through to the Ptolemaic era. Statues attributed to kings of the Archaic and Old Kingdom periods – Khasekhemui (Dynasty II), Khufu (Dynasty IV) and Neuserre (Dynasty V) – are used to argue the case for there having been some form of sanctuary or temple at Karnak dating back to at least the Old Kingdom, although it is acknowledged that it would have been (and remained for some time) considerably smaller than the then-existing Montu enclosure. And it must be admitted that there is no firm evidence of its being a temple dedicated to Amun, though the likelihood is that it was.

In the Middle Kingdom, Senusret I, whose extensive building programme at Karnak was most certainly in honour of Amun, dedicated much statuary to earlier kings: he honoured amongst others Sahure, Intef, Nebhepetre Montuhotep and Sankhkare Montuhotep, all kings who were commemorated later in Tuthmosis III’s Chamber of Ancestors. It is generally agreed that the statues of various Old Kingdom monarchs found in the Karnak cache do not necessarily imply that these actually dated from that period, but were, more probably, the work of later kings wishing to honour their predecessors who, they believed, had founded or contributed to an early sanctuary to Amun. Indeed, as just mentioned, it is acknowledged that Senusret I had dedicated several such statues. However, there is an exception. One statue of Neuserre (Dynasty V) was, according to Bernard Bothmer, a notable authority on statuary, an Old Kingdom statue ‘of undisputed date’ (Bothmer 1974: 168), which most certainly lends weight to the argument that an earlier temple had existed.

The ancient name for Karnak was Ipet-Sut, translated as ‘Most Select of Places’, a truly appropriate name for a temple. Strictly speaking, the term Ipet-Sut should only be applied to that central core of Karnak which lies between the Fourth Pylon of Tuthmosis I and the Festival Hall (Akh-Menu) of Tuthmosis III. Inscriptions on some of the later monuments themselves testify to this: the Hypostyle Hall of Seti I/Ramesses II was built ‘in front of Ipet-Sut’, and the single obelisk of Tuthmosis III, erected by his grandson in the Eastern Temple of Karnak, was described as being ‘in the neighbourhood of Ipet-Sut’. The origin and derivation of this name are uncertain, but the earliest known occurrences of it are found on two small monuments of the Middle Kingdom. On the West Bank at Thebes, in the mountains behind Deir el-Bahri, is a small mud-brick temple of Sankhkare Montuhotep of Dynasty XI. This temple, recently re-excavated by a Hungarian team (V¨or¨os and Pudleiner 1997: 37–9), is an interesting little building on several counts: it has the earliest known pylon entrance, which was topped with a limestone crenellation – a unique feature. Within the mud-brick enclosure there was a small chapel made up of a hall and three shrines, from which were recovered the remains of various limestone elements, and amongst whose fragmentary inscriptions can be seen the name Ipet-Sut (Nims 1965: 70). The other Middle Kingdom source for the name occurs on the so-called White Chapel of Senusret I (Dynasty XII) at Karnak (Lacau and Chevrier 1956: 77, para. 185). Although it is not known when the name first came into use, its writing within the White Chapel, using the final hieroglyphic determinative symbol three times to denote the plural, would point to an archaic derivation. Such a rendition to denote the plural is characteristic of archaic literary conventions. Later, plurals were generally rendered by the three plural strokes (|||), though it has to be said that in a religious context the older forms often continued to be used.

If the term Ipet-Sut was being used as early as Dynasty XI, this certainly seems to indicate that a temple to Amun was in existence at that time. The very meagre archaeological evidence of these early periods at Karnak itself could moreover show that there were indeed temples which preceded the sparse Middle Kingdom remains that still exist, as we shall see.

This, I hope, gives a little background to the temple and its possible origins. But, in truth, how little we know about so vast a site, though perhaps this is what gives it some of its appeal: mystery always adds another dimension and speaks to the imagination. French, Egyptian and other archaeological teams have been working for well over a century at Karnak, the central remains of which cover around ninety acres, and Greater Karnak (which includes the temples of Montu and Mut) around 750 acres. The excavation and research these teams undertake is, of necessity, a slow and painstaking business. Nevertheless, thanks to their continuing efforts, it is possible to unravel some of the complexities of the site by studying the remains and attempting to put them in their historical and chronological context, using original textual sources for additional information.

2

THE MIDDLE KINGDOM

The most ancient areas that remain at Karnak are the Middle Kingdom court, the White Chapel of Senusret I, and a large brick ramp which gives access to the Montu precinct on the north-west side, this latter not strictly a part of the temple of Amun. However, although the Middle Kingdom court was once the most sacred area of the temple, we can only guess at its splendour, for, sadly, it is also the most ruinous area. Much other evidence has come to light, as we shall see, giving tantalising glimpses of the early temple.

Senusret I (c.1971–1928 BC) must be considered the founder of Dynasty XII temple whose remains are, in some small part, still visible today in the Middle Kingdom court. This king was to place Thebes and Karnak at the centre of state and religious life by building a new temple to Amun under the god’s solar aspect – Amun-Re.

Senusret I was amost prolific builder: at least thirty-five sites have yielded monuments or buildings of the king, who also enlarged and enriched almost all the temples in Egypt which were already in existence. On a lintel from one of his many monuments (the temple of Re at Heliopolis) Senusret caused the following words to be inscribed: ‘The king dies not, who is mentioned by reason of his achievements’ (BAR I: para. 503). It would seem from all that he left behind him that he has been successful in this aim. As to Karnak, it appears that he built upon foundations of earlier temples, which he either pulled down or found in ruins. Several levels of flooring have been found below the existing pavements of the Middle Kingdom court, indicating that more than one temple had previously occupied the site (Lauffray 1980: 20–6; Gabolde 1998: 111).

There is no sure evidence as to which kings had founded these earlier temples. A few odd blocks and other fragments attributed to Nebhepetre Montuhotep have been discovered in various locations around Karnak (Habachi 1963: 35–6), but whether these can be truly dated to Dynasty XI, or whether they are elements dedicated to that great king by later rulers, is uncertain. However, considering the number of fine statues and offering tables of Amenemhet I (the first king of Dynasty XII) that have been unearthed, and also the belief that he may have erected an early shrine to Mut, Amun’s consort, he must be considered one likely candidate. It was, after all, Amenemhet I who raised the god Amun at Thebes to become a national deity, and who was the probable founder of the Beautiful Feast of the Valley when Amun of Karnak travelled, amidst great celebration, to the West Bank to visit Nebhepetre Montuhotep’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. Moreover, Amenemhet’s name was the first king’s name to be compounded with that of Amun. However, despite all this, it seems unlikely that Senusret would have pulled down his father’s temple and replaced it with one of his own, and it can hardly have been the case that he had found it in ruins. Indeed, it must be admitted that while there are many statues and the like, as mentioned above, of Amenemhet, there is a remarkable lack of architectural elements. Did Amenemhet perhaps, then, merely erect a small shrine or chapel, or did he enrich an already existing temple? Do we indeed have to consider earlier kings as possible founders of the temple to Amun? The evidence of the ‘platform’ underlying the so-called Middle Kingdom court implies that this perhaps was the case, but again architectural remains are virtually non-existent. In addition, there is nothing to indicate a building programme of Amenemhet I; it is Senusret I whose name is indisputably linked with the founding of the Middle Kingdom temple at Karnak.

It is, therefore, with the extensive, but dispersed, remains of Senusret I’s building activities that we can first begin to build up a picture, albeit patchy, of the early Karnak. The Middle Kingdom court, which lies behind the sanctuary of Philip Arrhidaeus, was set on a platform 40 m square; several layers of foundation levels have been identified here, as mentioned above, comprising a mixture of both limestone and sandstone blocks which had been reused from buildings of an earlier period (probably Dynasty XI), and this platform of blocks was itself founded upon an older base of mud-brick, possibly the vestiges of an even more ancient shrine or temple.

Today, there is very little to be seen in the Middle Kingdom court to give any impression of its original design. Three red granite doorsills are still visible in a line along the temple axis; these successive doorways once gave access to three rooms, the rear one assumed to be the sanctuary (Gabolde 1998: 114 and 118). Initially it was thought that in this final chamber must have stood the great alabaster base, whose broken remains have been found; these have been pieced together and the base restored to what was thought to have been its original position (Chevrier 1949: 12–13). It is a square pedestal, approached by a shallow staircase, and upon which several columns of text of Senusret are inscribed, whilst grooves on top of this pedestal indicate where some structure, perhaps a wooden shrine, had once stood. In the same area as these granite sills, remains of sixteen-sided columns in sandstone, bearing the cartouche of Senusret, have been found, as well as elements of a doorway whose inscription mentions a Year 20 of Senusret I, but more of this later.

The Holy of Holies, the deepest and most sacred sanctuary, which once stood in the court of the Middle Kingdom is now completely and totally destroyed. Looking at surviving examples from other temples, it must be assumed that, like them, it was a question of a room of small dimensions containing the naos (usually of granite) in which was housed the god’s statue, and in whose image was believed to have rested the great creative force – that divine power which sustained the entire universe. In New Kingdom and later temples, we know that the progress towards this sacred area became ever dimmer as the ground level slowly ascended and the roof level became lower; the doorways opened successively one after another until the king or high priest, the only people who were allowed to approach the god’s presence, finally stood before the closed doors of the naos, the very centre of the mystery and power of the ancient Egyptian temple.

From these general observations, one can begin to build up a picture of a typical small, symmetrical Egyptian temple, but until recently it has been almost impossible to say with any degree of certainty what that temple might have looked like and with what courts and chambers it might have been furnished. Whatever the original plan, however, there is no doubt that the Middle Kingdom court had contained the Holy of Holies, which remained in place for many centuries. In fact, it is probable that the entire court remained in use throughout much of the pharaonic period, though its internal arrangements and general environs were obviously adapted and altered.

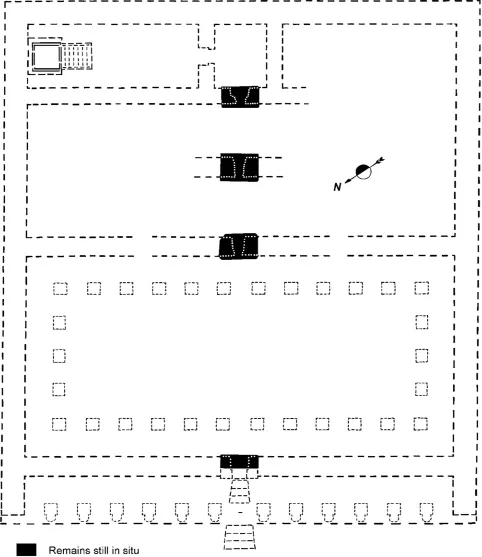

Little more was known for certain regarding this large blank area of Karnak until very recently, when the publication of in-depth research greatly expanded our knowledge of the Middle Kingdom temple. Thanks to the excavations of the Franco-Egyptian Centre at Karnak, and the work of Luc Gabolde in particular, it is now possible to visualise the very imposing structure that once constituted Senusret I’s temple dedicated to Amun-Re (Fig. 2.1).

Although the name of Amun-Re is attested at Karnak as early as the reign of Antef II, it was Senusret who undoubtedly was instrumental in merging the cult of the local god Amun with that of the sun god Re, and thus introducing a Heliopolitan element to the new temple (Gabolde 1998: 117). In later years – from the inception of the New Kingdom in fact – Karnak was often referred to as ’Iwnw-šm‘, the ‘Heliopolis of the south’. This assimilation was to have a profound effect upon the development of Karnak over the centuries, and Senusret himself was greatly revered by later kings.

Senusret’s temple stood within a surrounding wall of mud-brick that contained two small stone entrance gateways on the north and south sides, the lintels and jambs of which have been recovered in the area. The foundations of this mud-brick wall have been found exactly around the perimeter of the Middle Kingdom court platform (Gabolde 1998: 114 [185a]). The main entrance gate in the west wall would also have been in stone, but considerably larger in size, and probably flanked by mud-brick pylons. A lintel of Senusret I from just such a monumental gateway has been found, though its original location cannot be ascertained. As mentioned above, pylons were known from the time of Sankhkare Montuhotep (Dynasty XI), and these were already of a fairly impressive size. Indeed, the pylons of Ramesses III’s temple (Dynasty XX nearly nine centuries later) at Karnak were no bigger than those of Sankhkare’s mountain temple on the West Bank at Thebes, each wing of which had a width of 10 m.

The Middle Kingdom temple itself was constructed of limestone and measured in the region of 40 m square, with walls around 6 m in height. Its fac¸ade was preceded by a portico of twelve pillars, each one fronted by a colossus of the king in Osiride form, one of which has been unearthed from the foundations of the Sixth Pylon and is today in the Cairo Museum. Immediately behind the portico a central doorway led into a first court, considerably wider than deep, whose four sides were surrounded by a peristyle of square pillars. For decades, the existence of such a court had been known to Egyptologists, thanks to the discovery of the remains of several of the pillars (Legrain 1903: 12–14). As these were found very largely in the area now termed the Court of the Cachette (or court of the Seventh Pylon), it was assumed that Senusret had erected this peristyle court to the south, just outside the main temple. However, after re-excavation of the Court of the Cachette, which revealed absolutely no foundations or ancient soil levels, and painstaking research undertaken in storage magazines and archives, it has become apparent that Senusret’s court was in fact sited within the temple itself. Around the perimeter of this court once stood the limestone pillars, each side of which was carved with fine reliefs of the king, giving his full titulary and showing him worshipping in turn Amun, Atum, Horus and Ptah (Gabolde 1998: 89–93). This emphasised the king’s control over Memphis, Heliopolis and the Delta, as well as Thebes. Could this be an indication that, even at this early date, Karnak should be considered a state temple?

Figure 2.1 Plan of the Middle Kingdom temple (after Gabolde, L., Le ‘Grand Château d’Amon’ de Sésostris Ier à Karnak: pl. I).

These limestone pillars are not quite as high as those of the portico preceding it, which confirms that Senusret’s temple adhered to the age-old tradition of gently rising floor levels and descending roof levels as one progressed through the courts and halls towards the sanctuary.

Behind the main porticoed fac¸ade, the temple was divided into two: the western half was, as just outlined, occupied by the peristyle court. A doorway in the rear wall of this court gave access over the first of the three red granite sills, still in place, to a hall – perhaps a narrow hypostyle. From here an...