1 What is the IMF?

The origin of the IMF

On July 22, 1944 – in the aftermath of the Great Depression – 44 countries signed the “Bretton Woods Agreements” establishing the International Monetary Fund and its sister organization, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (now commonly known as the World Bank).1 The agreements were so-named after the Mount Washington Hotel at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire – the ski resort that hosted the International Monetary Conference of the United and Associated Nations, where the negotiations over the design of these two international institutions took place. The IMF and the World Bank have since come to be known as the “Bretton Woods” institutions. On December 27, 1945, after 29 countries had ratified the IMF Articles of Agreement, the IMF came into force.

Interestingly, the reason the IMF was formed has little to do with the economic programs in developing countries for which the IMF is famous today. Originally, the IMF was intended to monitor and help maintain pegged but adjustable exchange rates, primarily between the industrialized countries of Western Europe and the United States. The task of promoting economic development – development for war-torn Europe – was assigned to the institution that has come to be known as the World Bank. Also negotiated at the Bretton Woods Conference was an agreement that grew into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and eventually became the World Trade Organization, which was assigned the task of promoting freer trade among countries.

Why was an institution like the IMF deemed necessary? In an earlier era, during the end of the nineteenth century, countries had been on a strict “gold standard” of foreign exchange. The national currencies of different countries were all convertible into gold held on reserve by governments. This gold standard enforced discipline in the balance of payments between countries. If countries faced a balance of payments deficit – because, for example, the value of its imports exceeded the value of its exports – the requirement to back up domestic currency by gold would force the supply of money down. As a result, demand for imported goods would go down (because their prices would be too high), and the balance would right itself.

Box 1.1 The original members of the IMF

The Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund entered into force on December 27, 1945. By December 31, 35 countries had signed and otherwise indicated their intention to become members. These original members of the IMF (reported in the Summary Proceedings of the First Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors, September 27 to October 3, 1946) were:

Belgium Iceland

Bolivia India

Brazil Iran

Canada Iraq

Chile Luxembourg

China Mexico

Colombia Netherlands

Costa Rica Norway

Cuba Paraguay

Czechoslovakia Peru

Dominican Republic Philippine Commonwealth

Ecuador Poland

Egypt Union of South Africa

Ethiopia United Kingdom

France United States of America

Greece Uruguay

Guatemala Yugoslavia

Honduras

This gold standard imposed economic austerity on deficit countries, which was particularly costly to certain groups within these countries. As explained by economist Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, to maintain a fixed exchange rate in the face of a balance of payments deficit, domestic consumption must be cut – this often meant economic growth slowed, and unemployment rose.2

As laborers – who were hard hit by such changes – organized into unions and the right to vote was extended towards universal suffrage, resistance mounted against the discipline of the gold standard. Governments sought to avoid the austerity that maintaining the gold standard entailed when facing a balance of payments deficit. This led to all sorts of economic problems during the first half of the twentieth century. For example, some governments faced speculative runs of the national currency, where people exchanged the national currency for gold or for foreign exchange, fearing that the government would not maintain convertibility to gold. The fear that the national currency would lose value could become a self-fulfilling prophecy if enough people fled from the national currency. In the run up to the Great Depression, governments eventually engaged in “beggar-thy-neighbor” currency devaluations and erected barriers to trade to protect themselves from balance of payments problems, at the expense of world prosperity. In an era of democracy, where governments had other domestic priorities that took precedence over maintaining foreign exchange rates, the strict gold standard needed help.

Part of the proposed solution was an international credit union from which countries facing a temporary balance of payments deficit could borrow foreign exchange. Such a loan would allow countries to maintain a fixed exchange rate and soften the blow of austerity as the economy adjusted. Each country’s currency would still be backed by gold, but if national reserves of gold or foreign exchange dropped too low, there would be an international lending facility that could provide assistance.

Several specific plans were developed in the early 1940s. The British plan, entitled Proposals for an International Currency (or Clearing) Union, was developed by John Maynard Keynes, who was considered to be the greatest economist of his time. Keynes originally proposed the importance of international lending as early as 1919 when he talked of a post-war “international loan.”3 Following the Great Depression, Keynes proposed a “Clearing Union” with access to a pool of resources that could be lent to countries facing balance of payments deficits. Deficit countries would be required to adjust downward their consumption of imports so that deficits would not persist or widen, but loans from the Clearing Union would allow them to do so gradually to avoid domestic hardship. For such a plan to be effective, Keynes envisaged a Clearing Union with access to tremendous resources, particularly from countries with balance of payments surpluses.

In the years leading up to the Bretton Woods conference, the country with the largest surpluses was the United States, and the US was wary of Keynes’ plan, viewing it as potentially opening creditor countries up to unlimited liability.4 The US plan,5 developed by Treasury economist Harry Dexter White, called for all countries to make contributions to a much smaller “Stabilization Fund” from which countries facing balance of payments deficits could purchase foreign exchange. While the Keynes Plan called for contributions totaling $26 billion (with $23 billion from the US), the White Plan called for only $5 billion (with $2 billion from the US).6

These plans along with others – for example, a French plan and a Canadian plan – were negotiated throughout the early 1940s, ultimately resulting in the IMF Articles of Agreement at Bretton Woods. The result turned out to resemble the White Plan more than any of the others. The subscriptions to the IMF totaled $8.8 billion, with just $2.75 billion from the US.7

The resources of the newly formed IMF turned out to be insufficient to stabilize the economies and exchange rates of Europe following World War II. Rather than expand the size of the IMF, however, the US took it upon itself to assist directly with the Marshall Plan, providing a total of $13 billion in assistance to Europe between 1947 and 1953. The US wanted to have more control than the IMF would have allowed.

Indeed, the US would only provide Marshall Plan assistance to countries that did not seek additional assistance from the IMF.8 The IMF was essentially dealt out of the rebuilding process of Europe after World War II – dealt out of the very job the institution was created to perform.

So right from the beginning, the IMF did not play the role that it was created to play. Under the Bretton Woods system, the currencies of IMF members were allowed to fluctuate only within narrow bands. If the value of a currency dropped to the low end of the band, the IMF could and did lend to that country to shore up the currency. Such lending may have softened the blow of adjustment as the country brought down imports and brought up exports, but the problem was that it became increasingly difficult for countries – notably the US – to maintain their currencies in the face of fiscal deficits and expansionary monetary policy. All currencies were monitored closely by the Fund, and any devaluation was supposed to be approved by the IMF, but often countries went ahead on their own. It turned out that when countries failed to maintain their fixed exchange rate, more instability ensued than would have had the currency been allowed to float all along – especially if word leaked that the government intended to approach the IMF about a devaluation of the national currency. Particularly for industrialized countries, it became clear that market driven exchange rates were a more appealing alternative to the Bretton Woods system.

Eventually, the Bretton Woods system of foreign exchange collapsed. As the mobility of capital and foreign exchange increased in the 1950s and 1960s, it became too difficult and disruptive for developed countries to maintain the gold standard of the Bretton Woods system. In 1971, President Richard Nixon announced that the US would suspend its commitment to exchange dollars for gold. The following two years witnessed two devaluations of the dollar, a speculative attack on the pound sterling, and decisions by Switzerland, Germany, France and several other European countries to float their currencies. By 1973, the adjustable pegged exchange rates of the industrialized world were abandoned forever. The original raison d’Être of the IMF was gone.

Early involvement in the developing world

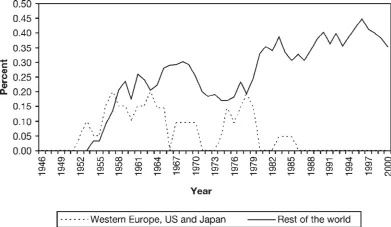

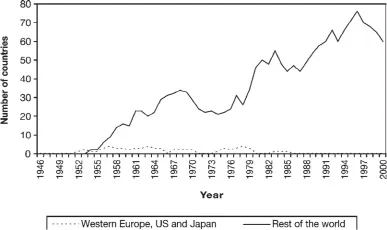

Many argue that it was at this point – during the 1970s – that the IMF shifted its attention from the industrialized world to the developing world, as the institution searched for a new purpose. People seem to love to hearken back to the early days of the IMF when it dealt with the industrialized world, not the developing world. A popular myth is that before the 1970s, the IMF engaged in truly temporary lending. Yet, the IMF never played as big a role in industrialized countries as originally intended. And while the very first loans the IMF provided did go to industrialized countries, the Fund began lending to developing countries as early as 1954 – a four year program for Peru began that year. As Figure 1.1 shows, by 1958 the percentage of non-industrial countries participating in IMF programs outpaced the percentage of participation among the US, Japan, and Western Europe. Looking at the actual number of programs, non-industrial countries outpaced industrial countries as early as 1956 (Figure 1.2).

If the IMF was created to facilitate international exchange among industrialized countries, what was the Fund doing in developing countries? From the beginning, the IMF was assigned – broadly speaking – two main tasks: (1) to monitor members’ economies – especially their exchange rates and balance of payments, and (2) to act as an international lender. Broadly speaking, this is what the IMF was doing – and still does – in the developing world. The loans to developing countries were consistent with the IMF mandate to provide balance of payments assistance, but instead of intervening in the exchange rates of the industrialized nations, it provided assistance – at increasing rates over time – to the developing world from the 1950s onward.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of countries participating in IMF programs.

Regarding the task of monitoring or “surveillance,” the IMF engages in bilateral discussions – called “Article IV consultations” – with nearly every country in the world – developed and developing alike. The Fund examines whether a country’s currency is overvalued and whether the exchange rate policies are appropriate. Over time, the IMF has increasingly examined other economic policies. A recent innovation in surveillance is a multilateral dimension, where the economic connections among countries are considered. The IMF is not as widely known for its monitoring activities, however, as it is known for its lending activities.

Figure 1.2 Number of countries participating in IMF programs.

The IMF’s actions as international lender are particularly conspicuous because when the IMF makes a loan to a government, the loan usually comes with strings attached. Recall that the Keynes plan called for gradual adjustment of domestic consumption, lest loans of foreign exchange finance ever-widening balance of payments deficits. Recall also the US concerns about unlimited liability for creditor countries. In the ...