1

The silents, 1913–1929

A Spanish Bull Fight

Filmed by an unknown Frenchman in 1900, A Spanish Bull Fight shows the bull being teased by men with capes, after which a bandarillo on a horse thrusts a dart into the bull’s neck and further bull-baiting ensues. Although the running time is less than one minute and the film was already more than twelve years old, the Gerrard Film Company submitted it to the BBFC early in 1913. When the BBFC was established at the beginning of that same year there had been no set rules relating to animal treatment, but A Spanish Bull Fight was nevertheless rejected on 14 March. This was one of 22 films rejected during the year, and in the first BBFC annual report, published early in 1914, ‘cruelty to animals’ figured as the first of the 22 stipulated grounds for cuts or outright rejection, although bull-fighting was not expressly mentioned. Within ten years the BBFC’s readiness to accept bull fighting was demonstrated by the award of a certificate to Blood and Sand, directed by Fred Niblo for Paramount, which opened in Britain in November 1922. Rudolph Valentino plays matador Juan Gallardo, and the film contains two bull-fight sequences which, as a contemporary reviewer noted, were ‘something of a novelty on the British screen’.1 The reason behind this reversal of BBFC policy is unclear, but one of the two bull-fight scenes involves the goring of Valentino because of his infatuation with Nita Naldi, the central theme, and is essential to the plot. However, despite this policy change, BBFC disapproval of cruelty to animals remained in principle and was eventually embodied into law in the 1937 Cinematograph (Animals) Act, still in force today. The Gerrard Film Company never resubmitted A Spanish Bull Fight, so that the BBFC ban was not rescinded later in the light of subsequent developments and technically remains valid. It is now a film curiosity and a very early example of censorship in operation, which the NFA preserved when it acquired a print in 1946.

A Woman or Charlie, the Perfect Lady

By 1915 Charlie Chaplin had gained a reputation as the cinema’s foremost comic and had moved from working with Mack Sennett for the Keystone company to the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company where he made fourteen films. One of these in 1915 was the two-reeler A Woman, directed by Chaplin himself. This film was probably the first in which the BBFC was confronted with transvestism, for Chaplin appears disguised as a woman. Moreover, an early sequence, incidental to the main story, shows a married man (Charles Insley) pursuing and then approaching a pretty girl (Margie Reiger) in a park. During 1915 the BBFC turned down at least one film for showing the premeditated seduction of a girl, so that it is just possible that the park scene fell into such a vague category and was the reason, rather than Chaplin’s transvestism, for BBFC concern. However, whatever the reason, the BBFC rejected A Woman when it was first submitted in March 1915, but later changed its mind, the film being released in Britain in the following July as Charlie, the Perfect Lady with the scenes of Charlie in drag not excised.2 In this instance the BBFC’s rapid second thoughts stand in contrast with Sweden, where A Woman remained banned from 1917 to 1931.3 The NFA acquired a print in 1939 as an example of Chaplin’s early work.

A Fool There Was

Directed by Frank Powell for the Fox Film Corporation in 1915, A Fool There Was was Hollywood’s first major sexploitation movie, heavily influenced by earlier Italian productions. It also marked the first appearance of Theda Bara as a femme fatale. Known in the film as The Vampire after a Rudyard Kipling poem, she plays a woman of notorious reputation who heartlessly destroys first the marriage of an American financier (Edward Jose) and then the man himself after his wife (Mabel Frenyear) inadvertently offends her. As a special American envoy to Britain he loses his place in British high society through his association with The Vampire after his wife has to remain in the United States to care for her injured sister. At length he turns to alcoholism and finally dies in the presence of The Vampire who, however, shows no remorse and simply leans over his body to scatter a few flower petals on his face. This particular scene, coupled with an earlier one in which the body of another lover (Victor Benoit) who had shot himself in The Vampire’s sight is taken from a ship while she merely laughs, allows Theda Bara to portray the ruthless ‘vamp’ to devastating effect.

In accordance with its general policy of not passing illicit sexual relationships, first openly declared in the 1915 annual report, the BBFC rejected A Fool There Was on 6 June 1916, although none of Theda Bara’s subsequent films (all now apparently lost) suffered a like fate before her popularity in ‘Vamp’ parts had waned by 1920. This inconsistency can be explained by the Home Office pressure for a new BBFC under governmental control which commenced in April 1916. This was to be fiercely resisted by all sections of the British film industry, but the Home Office did not abandon its plan until January 1917. Even then the danger was merely postponed rather than averted, for the government simultaneously announced its approval for a cinema commission of enquiry by the National Council of Public Morals (NCPM). New BBFC President T.P. O’Connor presented evidence of BBFC policies to this enquiry, and the enquiry finally delivered a report favourable to the BBFC and the censorship status quo in October 1917. Only then could the BBFC heave a sigh of relief, and while under interim pressure it inevitably came down on the side of caution. Thus A Fool There Was probably became the first screen casualty of British political circumstances and in consequence has seemingly never received a public showing anywhere in Britain. The Museum of Modern Art in New York donated a print to the NFA on 4 April 1957.

A Daughter of the Gods

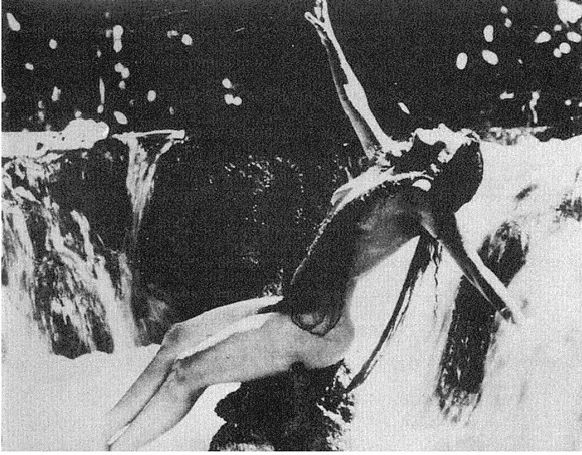

Directed by Herbert Brenon for Fox in 1916, A Daughter of the Gods features Australian swimming star Annette Kellerman as Nydia in an Arabian nights-style fantasy epic. The plot need not concern us here, for the solitary controversial sequences were the superfluous appearances of Nydia in the nude. The BBFC in 1915 had already rejected a film called Hypocrites because Truth had been depicted as a nude woman,4 and as a result the 1915 annual report had stated for the first time that nudity would ensure future rejection. When A Daughter of the Gods was first shown in the United States late in 1916, the nude scenes were included,5 and when it was screened privately to the British film industry early in February 1917, it received critical acclaim in the trade journals.6

While from April 1916 to October 1917 the Home Office was pressing for a state censorship and the NCPM commission of enquiry had yet to publish its report, some British distributors released major American productions without prior submission to the BBFC and thereby risked a prosecution because the BBFC’s precise legal powers were unclear. The most glaring example of this was the D.W.Griffith classic Intolerance which features industrial violence, the materialization of Christ, and bare breasted women, all of which had been condemned in BBFC annual reports. Intolerance was already showing at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, when in May 1917 impresario C.B.Cochran presented A Daughter of the Gods at the Stoll Picture Theatre in a première attended by members of the nobility. Quality press reviews were favourable,7 and to judge from the Home Office files at the Public Record Office there were no private protests. During September and early October 1917, by which time the main thrust of the NCPM report had become known, the film was

1 Annette Kellerman partly displays her natural assets in Herbert Brenon’s A Daughter of the Gods (Fox Film Corporation, 1916)

exhibited in Birmingham, Cardiff, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, and Sheffield.

A Daughter of the Gods has gone down in film history as the first movie in which a woman was seen nude. This takes no account of the seemingly now lost Hypocrites, but in any case to judge from surviving stills—no print of the film appears to exist in Britain—most of Annette Kellerman’s body was covered by her long flowing hair and only parts of her breasts are visible. This, together with the attendance of the upper crust of British society upon its release, suggests that Annette Kellerman’s ‘nudity’ has been somewhat exaggerated in film legend.8 Even so, it was evidently sufficient for the BBFC to be bypassed, although in the event no legal consequences ensued. The film has never been revived in Britain since 1917, and there is a pressing need for a British print to become available.

Civilization

Directed by Thomas M. Ince for his own Triangle company in 1916, Civilization is a celebrated anti-war classic, probably the best silent film of its genre. Even before it had reached Britain a contemporary trade review had described it as ‘primarily an argument against all kinds of war’.9

The opening shots focus upon a contented rural population in an imaginary kingdom going about their routine activities as farmers, wives, and mothers. Rumours of an imminent war emanating from a nearby town are greeted incredulously, while meantime the king (Hershall Mayall) holds council in his palace about a war he has already prepared for and decided upon. Luther Rolfe (J.Frank Burke), portrayed in the subtitles as ‘an ardent follower of the Christ—an advocate of Universal Peace’, speaks for peace in the parliament and infuriates the pro-war members who declare that pacifists are the ruin of any country and that war is necessary for any nation’s survival. Parliament drafts the war articles, whereupon the council tenders the pro-war advice it is known the king wishes to hear. Count Ferdinand (Howard Hickman), an inventor and a king’s favourite who himself supports war, is engaged to Katherine (Enid Markey) with the king’s blessing after Ferdinand has promised to invent a new war weapon.

The kingdom goes to war, the king saluting his troops as they march past on their way to the front. The war scenes follow, often reflecting the actual First World War events then in progress in Europe. Soldiers are seen undergoing trench privations under heavy artillery bombardment, while civilian suffering is also vividly depicted. The king’s army experiences heavy casualties, is thrown back by the enemy, and resorts to press-gang-style conscriptions of recruits against the protests and struggles of their womenfolk. One man is taken despite having an invalid mother confined to a chair who instantly collapses and overturns her chair. As enforced conscription is extended into the countryside, pressure for peace talks builds up from the women, and Katherine joins this peace movement.

In a sequence portraying Germany’s sporadic Atlantic Ocean unrestricted submarine warfare, Count Ferdinand, now a submarine commander, is given radio orders to sink a passenger liner, a reference to the sinking of the British liner Lusitania by a U-boat in 1915 when more than 120 Americans lost their lives. The order reads, ‘Sink liner Propatria with full cargo of contraband of war. Passengers used as blind. Disregard sentiment.’ He is about to obey when he has a vision of the sinking which includes the overturning of lifeboats in the water and drowning passengers. He flings open his uniform, proclaims himself God’s agent, and orders the torpedo loading to be stopped. He has to hold up the submarine’s first officer and crew at gun point, but in an ensuing struggle he opens a valve and the submarine is blown up. As the submarine sinks horrific scenes are shown of the crew drowning inside. All the crew are killed, but Ferdinand’s near dead body is picked up while his soul descends to ‘a haven of rest’, a visual image of hell. Christ is clearly seen and is referred to in the subtitle, saying to Ferdinand, ‘Peace to thee, child, for in thy love for humanity is thy redemption’. Ferdinand is granted absolution for his pro-war actions on account of his belated conversion to peace and is told his life will be spared provided that on earth he preaches peace.

He recovers, but his peace sermons produce pro-war riots and lead to his arrest close to the palace. Meanwhile cities are seen under bombardment and fierce naval battles occur. The king is close to accepting enemy peace offers based upon human rights, but when Ferdinand is brought before him, he orders a court martial. At this news Ferdinand faints, but the officer who tries to support him sees a vision of Christ holding the cross on which he was crucified. The king presides over the court martial where Ferdinand is condemned to death. However, by now strong peace movements have emerged in the kingdom, and when the king incorrectly hears that Ferdinand is dead, he decides to visit the latter’s cell. Here the king falls into a trance and encounters the spirit of Christ, whose image is superimposed upon Ferdinand’s inert body and then rises out of it. Christ takes the king through the cell wall to show him the battlefield and civilian slaughter realities. A riderless horse is seen persistently placing a hoof on his dead master’s body. Christ addresses the king, ‘See here thy handiwork?’, and finally reveals to him the book of judgment with his own name on a bloodstained page. Back in Ferdinand’s cell the king listens to the peace clamour and signs a peace treaty. The film closes with the populace and the returning troops reacting joyfully to the advent of peace.

Clearly Civilization had to be carefully and cautiously marketed for British consumption when the United States remained neutral and Britain had already experienced more than two years of war and in the process been compelled to substitute a life-and-death struggle for an initial expectation of a speedy victory. Through propaganda the British public had been led to believe that its cause had divine blessing, and as a result a film depicting Christ as an anti-war agitator might anticipate a rough reception. Accordingly in January 1917 Ince sent R.K. Bartlett to Britain specially to promote a shortened version of the film with the expanded title of Civilization: What Every True Briton is Fighting For.10 Bartlett evidently carried out his instructions efficiently, and the film was trade shown at the Marble Arch Pavilion early in February 1917. The trade reviews were cinematically favourable,11 but a fear was expressed that such a film might weaken the national will to win the war.12 This possibly explains why, despite Bartlett’s spadework, Civilization gained no immediate British release, although the BBFC had opposed the materialization of Christ since 1913 and the NCPM commission of enquiry had scarcely begun to gather its evidence. However, precedents for ignoring the BBFC were subsequently established with the London showings of Intolerance and A Daughter of the Gods, while by October 1917 the film industry’s fear of a state censorship had been removed and, probably more crucial, the United States had become a British ally against Germany. Consequently Civilization opened at the Regent Street Polytechnic in October and appeared at various other London cinemas until February 1918. The Home Office received only a few protests from the general public,13 but on the other hand the capital’s cinema-going public voted to some extent with its feet on Civilization, which had a much shorter London run than Intolerance.

If anti-war sentiment was unpopular with London cinema audiences in 1917 and early 1918, the position was perceived very differently early in 1931 when a sound track was added to Civilization following the impact of All Quiet on the Western Front, directed by Lewis Milestone for Universal in 1930. Films which had stripped the First World War of false heroics and uncritical flagwaving had appeared from time to time in British cinemas ever since May 1920 without any significant public protests. Consequently the British distributors, Equity British Films, submitted the sound version of Civilization to the BBFC, where it was rejected o...