![]()

PART ONE:

LEARNING DISABILITIES

Learning disabilities is the term used worldwide to indicate that there is a discrepancy between pupils’ school attainments and what they might be expected to achieve given their level of ability. In the UK this group of conditions is referred to as Specific Learning Difficulties. This term carries with it the assumption that if the difficulties can be remedied or circumvented by appropriate education or therapy then normal achievements will be attained. General learning difficulties refers to the profile of the slower learner who may also have specific learning difficulties. In some individuals the learning difficulties are overt and can easily be identified but in many other cases they are covert or silent and are frequently not identified. When giftedness and learning difficulties co-occur then they can cancel each other out and to all intents and purposes the pupil appears average in ability and attainment. There is evidence to suggest that some 50 per cent of pupils are affected by these silent difficulties.

Three children in 100 statistically have IQs above 130 so there is likely to be one in every class but in reality there are at least 5 or 6 potentially gifted children in every mixed ability class and many more with specific talents, and 50 per cent who are ‘more able’. The discrepancy diagnosis using an IQ test such as WISC-111 is a popular means of identifying specific learning difficulties such as nonverbal learning difficulties and dyslexia but there are questions about its sensitivity and relevance. Alm et al. (2002) concluded that even the ACID profile (difficulties with Arithmetic, Coding, Information and Digit span on WISC) was a group phenomenon but did not refer to any individual dyslexic.

Three different groups of underachievers are known to exist:

Group 1 (usually identifiable)

- those who have been identified by discrepancies between high scores on ability tests and low achievement in school subjects, attainment tests, or SATs

- those who show discrepant scores on IQ tests between verbal and performance items (for example, CAT scores) but may be performing in class at an average level

- those who show an uneven pattern of high and low achievements across school subjects with only average ability test scores

- those whose only high achievements seem to be in out of school or non-school activities

Group 2 (usually the disability masks their abilities)

- those who have a specific learning difficulty – dyslexic type difficulties in the presence of average reading test scores and school attainments

- those with spelling or handwriting difficulties and average or below attainments

- those with gross motor coordination problems, or sensory impairment and average or below school attainments

Group 3 (usually not identified)

- pupils with social and behavioural difficulties

- daydreamers, uninterested in school, or ‘lazy’ pupils

- linguistically disadvantaged background but average ability and functioning – showing a great deal of compensation going on.

All three groups have learning difficulties, many of which have not been identified. Group 1 pupils, although they have some high scores on ability tests, will have underlying learning difficulties which can be uncovered and given support and will need curriculum modifications and changes in teaching strategies in order to profit. Group 2, because of their overt double exceptionalities, have patterns of depressed scores on abilities tests that mask their potential, or their difficulties are focused upon and their giftedness is not attended to. They will need a ‘talking curriculum’ while being given specialist support for their specific learning difficulties. Group 3 underfunction for a variety of reasons such as the need for the ‘cool’ image in boys so they fear to try in case they fail, or their ‘culture’ is that school is not ‘cool’. Others fear the label ‘boff and the bullying that can ensue. Girls may develop similar images about what is ‘cool’ and ‘uncool’ but also become vulnerable, especially in co-educational schools, to seeking not to do well or pursue such ‘non feminine’ subjects as maths or be seen to work hard. For them it even becomes ‘childish’ to do what the rest of the class is doing; they prefer to sit out and chat. Some pupils come from a linguistically disadvantaged background that hampers their ability to express themselves adequately in ‘academic’ subjects or in school life as a whole and practice in talking and listening is essential.

Underlying all of these underachievements a low sense of self esteem is to be found with a range of strategies being used to defend the sense of self or to prop it up. Characteristic also is the need in these pupils to have something interesting and challenging intellectually to engage with. But because in many classrooms the lessons are teacher led and information is imparted verbally, has to be recorded in writing and then learned, these pupils lose motivation as their involvement in making meaning for themselves diminishes. Most commonly they find school ‘very boring’, and if they cannot achieve top levels in SATs they feel undermined and grow disaffected as their failures and perceived failures multiply.

The curriculum manager needs to encourage all departments to identify the top 20 per cent of pupils in their subject area in each class or year. This will enable the building of patterns on a grid which shows, for example, subjects, CATs test scores, SEN and behaviour problems. Particularly significant will be the identification of pupils who are good orally but ‘cannot write it down’ or only very good when there is some kind of problem to solve, or have a lot of common sense but only ‘good average attainment’; excellent at art or PE but ‘no good’ at so called academic subjects; a leader in every bit of mischief but not school work. The Special Educational Needs Coordinator will have an important contribution to make as do parents and the pupils themselves.

We know that boredom and lack of cognitive challenge in the daily curriculum is playing a major role in causing more pupils across the ability range to become more disaffected and underfunctioning than was formerly the case. Gifted and underachieving pupils are particularly vulnerable. An inservice training strategy for key staff such as learning mentors, ‘G and T’ coordinators, and SEN staff should begin with shadowing one pupil for a day to see exactly what pupils are subjected to.

The four chapters in this Part discuss a range of approaches and strategies which are typical of the field. The first two illustrate the complexities of cases in remediation and curriculum provision. The second two deal with verbal and non-verbal learning difficulties. In chapter one Kokot details the methods she uses based upon ‘HANDLE’ (Holistic Approach to Neurodevelopment and Learning Efficiency) to overcome the complex and deep learning disabilities of her students. This approach, in which underlying mechanisms and pathways are addressed, is reinforced and further exemplified in chapter four in relation to non-verbal learning disabilities. In chapter two, Stewart gives details of how the curriculum for students with a range of learning disabilities can be modified and differentiated to meet individual patterns of needs based upon her case work with the gifted. chapter three looks specifically at dyslexic type difficulties in gifted undergraduates and how their needs can be met in curriculum and remedial terms and then traces these difficulties back to school and kindergarten age showing what should have been done to help them. A hidden population of gifted dyslexics with residual spelling problems masking their abilities is identified as well as methods for overcoming their difficulties. chapter four deals with the more neglected areas of non-verbal learning difficulties in handwriting and coordination difficulties as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Each non-verbal learning disability can mask high ability and talent but some unfortunate pupils have both non-verbal learning disability and dyslexia.

Reference

Alm, J. and Kaufman, A. S. (2002) ‘The Swedish WAIS-R factor structure and cognitive profiles for adults with dyslexia’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35(4), pp. 321–33.

![]()

1

A neurodevelopmental approach to learning disabilities: diagnosis and treatment

Shirley Kokot

The question of why some gifted children fail to thrive in school is a tantalising one that has occupied researchers for many years. Underachievement is usually considered to be the result of individual, family and/or school-related factors (Baker, Bridger and Evans 1998) but many gifted children are recognised as having neurobiological problems that interfere with academic and social/emotional functioning. It is common practice to label these according to the symptoms they manifest. Labels frequently used include ADD, ADHD (Leroux and Levitt-Perlman 2000), Visual or Auditory Perceptual problems, Tourette's Syndrome, Dyslexia (Winner 2000), Dyspraxia, Asperger's Syndrome (Neihart 2000), Autism (Cash 1999), and so on. These conditions may be accompanied by learning disabilities that persist in spite of diverse therapies being tried by often desperate parents.

Therapeutic approaches to learning disabilities

Many different therapies exist that claim to successfully treat particular learning disabilities. It is not within the scope of this chapter to discuss each one but suffice to say that too few have had significant success and so the search continues for real understanding of what causes the behaviours that impede learning.

Most gifted children with learning disabilities show a scatter of high and low abilities across different tasks. Early theorists and specialists in the field of learning disabilities believed that composites of traits or faculties (called ‘processes’) were activated when a child performed a task. Weakness in one or more of the processes would account for the child's failure on the task. Following this, it seemed logical that strengthening the faulty process would lead to improvement of the child's performance (Farnham-Diggory 1992). Among these specialists were Ayres, who focused on sensory integration; Kephart, on perceptuomotor matching; Frostig, on visual-perceptual training; Delacato, on neurological organisation, and many developmental optometrists, who believed that aberrant visual systems have an impact on reading and subsequent learning. However, during the 1970s and 1980s these theories and related practices were evaluated and found to be scientifically invalid and ineffectual. Despite such criticism and coupled with the fact that later practitioners using those approaches did not effectuate the predicted successes, these therapies are still utilised in many countries around the world.

The late 1980s and 1990s saw an explosion of brain research that clarified some issues and, indeed, led to support for the basis of many of the earlier theories. It seems to be accepted now that movement is responsible for the structure of the brain (Changeux and Conic 1987; Ito 1984; Lisberger 1988) and that the brain's proven plasticity means that through movement it becomes possible to restructure the brain (Le Poncin 1990). These findings mean, in effect, that the body organises the brain rather than the other way around. Given this understanding of how the brain functions, it is likely that individuals struggling to cope with the demands of life and learning may be doing so not because of brain damage in a specific area of the brain, but rather due to inefficient functioning of several interactive sensory and motor sub-systems. Take the example of dyslexia. Previous thinking attributed the problem to an impairment within the language centre of the cerebral cortex. Evidence now suggests that the person with dyslexia may be manifesting deficits of visual memory, directionality, visual tracking, concentration and delayed processing of auditory and/or visual stimuli.

In his studies of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Lewis (2001) found that more sub-systems and more energy may be required by some individuals to function, giving rise to myriad difficulties. This concurred with the theories of Bluestone, who has been successful over the past 35 years in treating individuals of all ages with a wide range of problems. She has integrated recent and more long-standing knowledge and arrived at new insights as to the origins and treatment of learning difficulties. These she has evolved into the HANDLE approach, the acronym standing for Holistic Approach to NeuroDevelopment and Learning Efficiency.

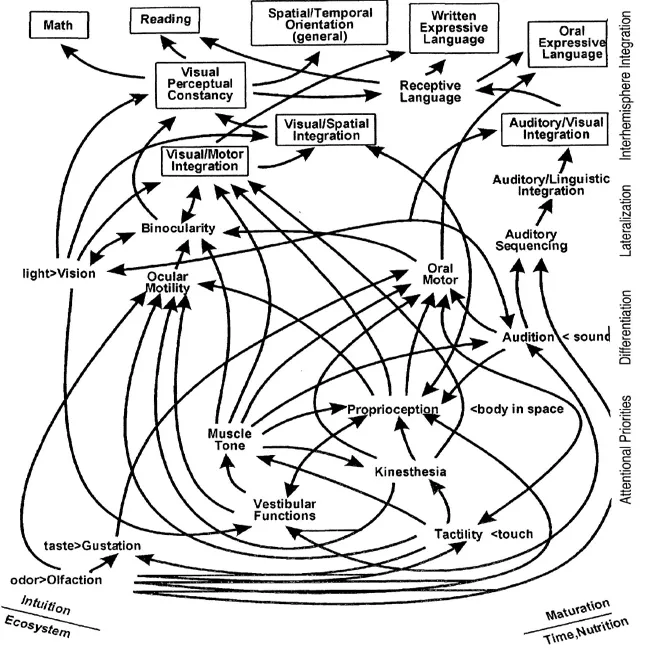

A hierarchy of integrated systems

Figure 1.1 shows the chart that Bluestone developed to represent diagrammatically the integrated and interdependent sub-systems responsible for our efficient functioning. The relative position of each sub-system on the chart is indicative of the hierarchical nature of the neurological system, and illustrates how higher level functions depend on those at a lower level. For example, problems with reading or maths may be traced all the way back to a dysfunctional vestibular system. In this way, HANDLE attempts to identify the roots of a learning problem. Practitioners drafting a therapy plan would sequence and prioritise exercise activities according to where an individual's weaknesses would show up on the hierarchy.

Lowest level systems would be addressed first so that, strengthened, they may support the functions of higher level systems, which could then benefit optimally from corrective therapeutic activities. To address ‘higher level’ functions – which, in this paradigm, amount to splinter skills – before strengthening the weakened foundational systems is an exercise in futility: frustrating to the child and the teacher because such an approach achieves at best minimal gain, and serves only a stop-gap purpose. While such an approach may possibly improve a particular splinter skill at the time, it would not resolve the causal issue. This results in the weakness remaining to affect other skills – possibly simultaneous in time, such as interpersonal and emotional skills, but assuredly skills that show up later – needing those same weak foundations. In addition, even if the higher level function is relatively intact, energies from these higher levels may be used to compensate for a weakness in a more foundational system, emphasising the need to address inefficient functioning of lower level systems. For example, if a child's visual system is well developed, but the tactile system is hypersensitive, s/he may use vision to remain hypervigilant of the surroundings rather than to use it freely for tasks of visual discrimination (Bluestone 2001a).

Figure 1.1 Chart showing Bluestone's representation of integrated and independent sub-systems. Source: Bluestone (2001b)

Diagnosing the root causes of learning difficulties

The HANDLE perspective defines neurodevelopment not as a given sequence of accrued skills but as an interactive hierarchy of brain functions, with a vestibular foundation for skills (such as speech, maths, visual tracking and so forth) presumed by other perspectives to be isolated in particular sites in the brain. When neurodevelopment is understood as interactive, no time frame limits brain function. Learning is thus the lifelong process of using sensory, motor, social and emotional input to realign output into effective behaviour (Suliteanu 2001). The holistic nature of the approach also requires recognition of internal and external influences. This means acknowledging possible causal roles of chemicals, allergens, nutritional deficits (especially the absence of essential fatty acids), dehydration and toxins of any kind. In addition, it includes the individual's social environment, such as the increasing cocooning lifestyle that keeps children indoors and inactive and the decreased demand on their creativity as a result of graphic media (Suliteanu 2001).

Each learning disability and each individual has unique aspects, but the trained observer can determine patterns of dysfunction in the neurological subsystems required to support learning. Those patterns then suggest how to resolve the disability with gently progressive strengthening of the weak areas. Crucial observation during assessment of the individual learner includes:

1. what distracts attention from the task at hand

2. what requires energy needed for comprehension

3. what physical/environmental changes affect the learning, and

4. what learning modalities are most successful.

An interactive, non-standardised evaluation protocol identifies such factors as:

1. distractions due to tactile or auditory hypersensitivity

2. vestibular inadequacy to support muscle tone, visual tracking and linguis-tic/phonetic awareness simultaneously

3. irregular interhemispheric integration interfering with auditory-visual integration, parts-to-whole configuration as well as problems with central auditory processing due to an inability to integrate the word/language component with the picture/meaning of the word

4. light sensitivity and visual-motor dysfunctions that cause irregular visual/v...