- 362 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Landscape and Film

About this book

Landscape is everywhere in film, but it has been largely overlooked in theory and criticism. This volume of new work will address fundamental questions: What kind of landscape is cinematic landscape? How is cinematic landscape different from landscape painting? How is landscape deployed in the work of such filmmakers as Greenaway, Rossellini, or Antonioni, to name just three? What are differences between the use of landscape in Western filmmaking and in the work of Middle Eastern and Asian filmmakers? How is cinematic landscape related to the idea of a national cinema and questions of identity. The first collection on the idea of landscape and film, this volume will present an impressive international cast of contributors, among them Jacques Aumont, Tom Conley, David B. Clarke, Marcus A. Doel, Peter Rist, and Antonio Costa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Landscape and Film by Martin Lefebvre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & Videoone

the invention of place

danièle huillet and jean-marie straub’s

jacques aumont

translated by kevin shelton and martin lefebvre

We know a great deal about the origins of this film, Moses and Aaron. The premise, like many other films by Straub and Huillet, remains a desire to confront the medium of film with a preexisting text that somehow resists it. Such as the text of Othon, by Pierre Corneille, which resisted being captured on film with its highly compact intrigue and the essentially foreign character of its seventeenth century language, Arnold Schoenberg’s opera poses its own difficulties. It resists being captured on film by the density of its politico-theological debate, by the violence of its intrigues around power, not to mention its strange musical composition, with its technique of twelve tones that forces us to deal with a musical language we are not accustomed to hearing. In each case, the filmmakers’ preoccupation was to superimpose a film script over the drama of the text—because film is not theatre—without, however, altering the nature of the drama specific to the text.

Scripting, in this case, is not an exercise of adaptation, nor is it a narratological or compositional analysis. In classical theatre, the most obvious elements of scripting, from the very first reading of the text, are the entrances and exits indicated in the stage directions, often underscored in the text itself (e.g., “Leave!” “Here she is!”). In the filming of Othon, Straub and Huillet constantly make use of these natural dramatic articulations of the text, more often than not, by emphasizing them cinematically (for example, ensuring that the character remains invisible to the camera before suddenly appearing with a twist of the camera, or the reverse, by including the receding footsteps for a long time after the character has left the image). This technique is sometimes used in Moses and Aaron; at least once, when the Hebrews see the two brothers arrive from afar, they comment on their almost supernatural allure; and when finally the choir sings “See Aaron! See Moses! They have come at last!”, the panoramic camera roams to show them, motionless in the middle of the set. And yet, the libretto by Schoenberg seldom uses this type of dramatic scripting; the transitions are rarely marked by an entrance or an exit. Moreover, the Schoenberg style is based on—and this is perhaps one of the few constants in the diversity of his works—the absence of clear scripting into parts, movements, or sections. The scripting, in the case of the film, therefore, needs to be ensured through other means.

In the filming of Othon, another technique was tried and developed: the use of a visually impressive location, at once dramatically practical (perhaps even capable of proposing its own unique solutions for découpage and mise-en-scène), and historically charged. In their treatment of the opera Moses and Aaron, Huillet and Straub underscored the work’s segmentation by either introducing or uncovering a number of transitions by shifts in framing. However, if the film was able to maintain its own strength as a film, while confronted with that of the text of the opera, it is in large part due to the filmmakers’ careful selection and use of location. The locations in the text by Schoenberg are only sketchy biblical locations. They act as a support for the primary episodes: the place of the revelation; the place where Moses meets Aaron; as well as places for the long public address for two voices before the people, for the encounter with God, for the pagan orgy, and, finally, for the punishment of Aaron. Even more than the purely theoretical palaces of Corneille’s or Racine’s emperors, these are symbolic locations, almost entirely coinciding with their specific names. It is therefore not at all surprising that practically every mise-en-scène of Moses and Aaron in the theatre retained only the first term of the specific names. The tension created between the abstract power of these names (the Burning Bush, Mount Sinai, the Desert) and their concrete configuration, which they must exhibit to effectively serve as a support for the drama, follows the emphasis suggested by the text and the music of an underscored metaphysical abstraction: no landscape, no geography. In the theatre, they are usually rendered purely as symbolic spaces, almost as if they were being staged for Wagner.

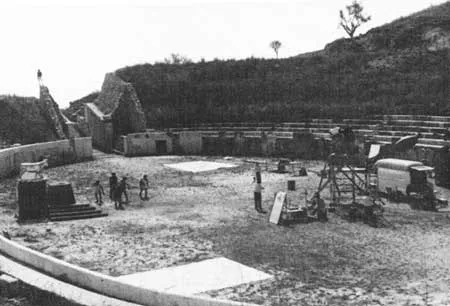

Naturally, the setting for the film of this opera is confronted by a similar question, but with completely different means. Whatever scenic option is chosen, the film has a real difficulty escaping the possibility of the emphasis being placed at the other pole, that of documentary realism, where the apparently singular, concrete determinations of the locations become dominant. An adaptation in the Hollywood spirit would not have hesitated to multiply the sets and settings, preferably picturesque ones as was the case with Joseph Losey’s Don Giovanni or Francesco Rosi’s Carmen which, even though shot in Europe, were driven by the same interest in the spectacular. Straub and Huillet’s remarkable solution is entirely different: manifestly dialectic, it neither renounces visibility, i.e., concrete, singular, and historical existing space, nor abstract symbolism. Indeed, for the first two acts of the opera—the part that was actually composed by Schoenberg, the third act never having been completed1—the filmmakers chose a striking and astonishing location: a Roman amphitheatre from the first century, situated in the middle of the Apennines, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) east of Rome (Figure 1.1).

There is little to add to the very precise and lucid comments made by the filmmakers about the choice of this location.2 The decision to film everything in one location does however multiply the constraints (i.e., reduces the choice of possibilities). The location had to be practical: accommodate two characters as well as a whole chorus, a caravan of different animals as well as the imprecations of the prophet, not to mention the dance before the golden calf. Moreover, it had to be out of the way of tourists and sheltered from onlookers, especially inopportune noises; it should be in a location with little threat of rain. It had to be historically and symbolically congruous: preferably an ancient site (and, given our relation to Antiquity, a monumental site). Its geography needed to be striking: it is a plateau. Finally, since it was to accommodate a representation of a semitheatrical nature, it should also have certain intrinsic visual and acoustic qualities, and more fundamentally, retain some trace of the work’s origin in the theatre (not to mention in music). We know the solution for this multifaceted problem: everything except for the third act was filmed in the amphitheatre of Alba Fucens, close to the city of Avezzano, in the Abruzzi region.

Figure 1.1

The amphitheatre of Alba Fucens. Production still.

The amphitheatre of Alba Fucens. Production still.

This decision brought with it innumerable problems, both materially and intellectually, not to mention some very real headaches. But it surely manifests a desire not to forget the theatre, incarnated once and for all in the film’s scenography. It is also, perhaps more indirectly, an effect of taking very seriously the documentary nature of what is called the cinématographe. If the latter is capable of rendering a location—and not simply, as in theatre, the constructing of a dramatic space or a functional substitute for it; but if the film is to exploit the vividness, the very smell3 of a place—then it is necessary to find a setting whose strong visual and symbolic presence imposes itself as such, so that the filming can bring these concrete qualities to light.

There to be read in the amphitheatre of Alba Fucens are the layers of History. It was built in the year 40 of our calendar, just a few years after the death of the prophet Jesus, also known as Christ, under the brief rule of Caligula, marked, amongst other things, by the mad emperor’s penchant for festivities and exotic religions. The choice of this site for framing a biblical action is, in itself, a powerful image that links together the Old and New Testaments, in much the same manner as the figural interpretation of the Bible proposed by the Church Fathers4 (e.g., St. Augustine sees Moses as a figura Christi, and the Ministry of Aaron as an umbra and a figura of the eternal Ministry).5 Such an amphitheatre, in a province of the Roman Empire, probably served for games (though its architecture does not seem to suggest this), but certainly for religious, civil, and sacrificial festivities. Caligula had reestablished the Egyptian cult of Isis, banned by Tiberius, and his immediate successor, Claudius, was the first to chase the Jews from Rome.6 Of course, Moses and Aaron is a Jewish story, not a Christian or pagan narrative. Choosing this amphitheatre to stage it both contradicts the story and adds new elements to it: it lets Roman history and Christian history break into biblical history. Furthermore, innumerable similar amphitheatres have figured in numerous genre films such as ancient epics (with gladiators) and Christian epics (with lions); these have acquired a particular iconographic weight, which Alba Fucens implicitly evokes in our memory.

This idea of an implicit evocation, of an underground reservoir (of meaning, of memory, of history, of death) whose task it is for the landscape to conjure, is an eminently recognizable one, for it constitutes within Straub and Huillet’s cinema a quasi-authorial thematic trait.7 In almost every one of their films, the landscapes are immense tombs, cenotaphs, or monuments to some anonymous martyrology. For instance, Fortini Cani has long panoramic shots of the villages of the Alpuan Alps, where some Oradour-like Nazi massacres took place. These shots are silent, only supported by the sentence that precedes them and which offers the key to understanding them. There is nothing in these shots, only beautiful, ancient, and austere homes; or again, in another village, brand new low-income housing (yet already showing their wear and tear), where children play and trucks roll by on the road in the distance (there is an irresistible feeling of war); and from time to time, a marble slab makes an appearance, ex voto. The Italian countryside, as the character of the second part (De la nuée à la résistance) finds out, is soaked in the blood of its partisans; while the Dialogues of the first part tell us that this countryside was, in a time before our own, in the time of myths, populated with gods and when men were once like the gods (eritis sicut Dei: another infraction, of Christianity into paganism this time). As well, we can think of the adaptation of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Coup de dés situated in Père-Lachaise, in front of the Wall of the Federates; or again, of Othon, which begins with a shot of the opening of a cave where, during World War II, the Communists had hidden their weapons. Or even again, the landscapes of Lothringen! which exude their historical weight (the weight of massacres and exploitation) as they are seen through both long and medium shots.

But how can we come to know all that which the image can never sufficiently say? (After all, the flip-side of the image’s strength and also its limit is that it can only show.) The most expedient way is to verbally state the necessary information: theories of facts (Marzabotto in Fortini Cani), or litanies of numbers (the commentaries of Engels about the French landscapes in Trop tôt, trop tard!). The most expressive is, perhaps, to create a filmic figure, where something from in and under the ground is brought to light. In the great confrontation scene between Galba and Camille, in act II of Othon, this chthonic subsoil manifests itself through an immense cavity that we see—a gaping hole in the background at the right behind Galba, in the shot where he appears for the first time. The inscription of the bodies of the “actors” or “models” into these locations needs to be taken literally; after all, each shot institutes a particular relationship between each of them and the site from which they either stand out or are embedded. Consequently, at the mysterious cave, opening beside Galba, which is made visible through a slight reframing of the image, we need to add, for example, the triple historical setting that delimits the space that Camille occupies (on the left, the baroque palaces; on the right, antique stone walls in ruin; in the back and lower than her face, the carriages).

There is no voiceover in Moses and Aaron to tell us what haunts this location that we see: the implicit evocation is consummated, so to speak, by the fact that everything, from in and under the ground, is channelled through the human figures of the drama, in their costumes, postures, and gestures, as if they had just sprung up there, like flowers (like a Valerian marine cemetery, where “le don de vivre est passé dans les fleurs” [the gift of life is passed down in the flowers]). This is why such a location must be treated with care, if not a particular meticulousness—even if it is not a piece of nature that needs to be respected on principle or by devotion. In both, Empedocles and in Antigone as well, Straub and Huillet have pushed to the limit the art of walking on, without stepping on, a location so that it is not flattened or changed by the mere act of being filmed.8 This extremely similar treatment of the amphitheatre of Alba Fucens, albeit far less fragile than the brush on the slopes of Etna, demonstrates that the approach is not just an obsession; nor is it inspired by some desire for cleanliness or even some moral desire (“ecological,” as some commentators have smirked), but remains an aesthetic decision that is simultaneously a political decision. By refusing to leave any visible traces of their filming, Straub and Huillet enjoin themselves to not add any visible stratum, either to the history or the visibility, of their locations. Their locations are forever marked by having played host to a film—but this mark should never be conspicuous: it must become another subterranean mark, identical to the nature of all the other marks that each film evokes. The location should have been transformed, not in its appearance, but in its being (Figure 1.2).

Once this relationship of intimacy, of an essential connivance as it were, has been established with a location, the question of whether it can be considered an effective ground for the mise-en-scène as well needs to be addressed. The arena of Alba Fucens possesses properties common to all such amphitheatres that are remarkably useful: its form is hollow, focusing the drama more than enclosing it. It allows, without any artifice (beyond the one of its selection), framing the drama and preventing it from becoming dispersed. The oval shape of the arena is good, conjoining the rounded—which closes—and the elongated—that orients, providing a clean, marked axis. Everything is incessantly brought back to the ground, where the red dust covers the surface of the elliptic-shaped interior; on this, the barest imaginable background, the characters stand in draped clothing (a stylized antiquity) and seem to emerg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- TitlePage

- Contents

- illustrations

- acknowledgments

- introduction

- 1. the invention of place: danièle huillet and jean-marie straub’s

- 2. between setting and landscape in the cinema

- 3. toward a genealogy of the american landscape: notes on landscapes in d. w. griffith (1908–1912)

- 4. the course of the empire: sublime landscapes in the american cinema

- 5. asphalt nomadism: the new desert in arab independent cinema

- 6. the inhabited view: landscape in the films of david rimmer

- 7. sites of meaning: gallipoli and other mediterranean landscapes in amateur films (c. 1928–1960)

- 8. the presence (and absence) of landscape in silent east asian films

- 9. from flatland to vernacular relativity: the genesis of early english screenscapes

- 10. landscape and archive: trips around the world as early film topic (1896–1914)

- 11. a walk through heterotopia: peter greenaway’s landscapes by numbers

- 12. landscape and perception: on anthony mann

- 13. the cinematic void: desert iconographies in michelangelo antonioni’s zabriskie point

- contributors

- index