- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Illustrated with over fifty photos, Civilizing Rituals merges contemporary debates with lively discussion and explores central issues involved in the making and displaying of art as industry and how it is presented to the community.

Carol Duncan looks at how nations, institutions and private individuals present art , and how art museums are shaped by cultural, social and political determinants.

Civilizing Rituals is ideal reading for students of art history and museum studies, and professionals in the field will also find much of interest here.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Civilizing Rituals by Carol Duncan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

History of Art1

THE ART MUSEUM AS RITUAL

This chapter sets forth the basic organizing idea of this study, namely, the idea of the art museum as a ritual site. Unlike the chapters that follow, where the focus is on specific museums and the particular circumstances that shaped them, this chapter generalizes more broadly about both art museums and ritual. Besides introducing the concept of ritual that informs the book as a whole, it argues that the ritual character of art museums has, in effect, been recognized for as long as public art museums have existed and has often been seen as the very fulfillment of the art museum’s purpose.

Art museums have always been compared to older ceremonial monuments such as palaces or temples. Indeed, from the eighteenth through the mid-twentieth centuries, they were deliberately designed to resemble them. One might object that this borrowing from the architectural past can have only metaphoric meaning and should not be taken for more, since ours is a secular society and museums are secular inventions. If museum facades have imitated temples or palaces, is it not simply that modern taste has tried to emulate the formal balance and dignity of those structures, or that it has wished to associate the power of bygone faiths with the present cult of art? Whatever the motives of their builders (so the objection goes), in the context of our society, the Greek temples and Renaissance palaces that house public art collections can signify only secular values, not religious beliefs. Their portals can lead to only rational pastimes, not sacred rites. We are, after all, a postEnlightenment culture, one in which the secular and the religious are opposing categories.

It is certainly the case that our culture classifies religious buildings such as churches, temples, and mosques as different in kind from secular sites such as museums, court houses, or state capitals. Each kind of site is associated with an opposite kind of truth and assigned to one or the other side of the religious/ secular dichotomy. That dichotomy, which structures so much of the modern public world and now seems so natural, has its own history. It provided the ideological foundation for the Enlightenment’s project of breaking the power and influence of the church. By the late eighteenth century, that undertaking had successfully undermined the authority of religious doctrine—at least in western political and philosophical theory if not always in practice. Eventually, the separation of church and state would become law. Everyone knows the outcome: secular truth became authoritative truth; religion, although guaranteed as a matter of personal freedom and choice, kept its authority only for voluntary believers. It is secular truth—truth that is rational and verifiable—that has the status of “objective” knowledge. It is this truest of truths that helps bind a community into a civic body by providing it a universal base of knowledge and validating its highest values and most cherished memories. Art museums belong decisively to this realm of secular knowledge, not only because of the scientific and humanistic disciplines practiced in them—conservation, art history, archaeology—but also because of their status as preservers of the community’s official cultural memory.

Again, in the secular/religious terms of our culture, “ritual” and “museums” are antithetical. Ritual is associated with religious practices —with the realm of belief, magic, real or symbolic sacrifices, miraculous transformations, or overpowering changes of consciousness. Such goings-on bear little resemblance to the contemplation and learning that art museums are supposed to foster. But in fact, in traditional societies, rituals may be quite unspectacular and informal-looking moments of contemplation or recognition. At the same time, as anthropologists argue, our supposedly secular, even anti-ritual, culture is full of ritual situations and events—very few of which (as Mary Douglas has noted) take place in religious contexts.1 That is, like other cultures, we, too, build sites that publicly represent beliefs about the order of the world, its past and present, and the individual’s place within it.2 Museums of all kinds are excellent examples of such microcosms; art museums in particular—the most prestigious and costly of these sites3—are especially rich in this kind of symbolism and, almost always, even equip visitors with maps to guide them through the universe they construct. Once we question our Enlightenment assumptions about the sharp separation between religious and secular experience—that the one is rooted in belief while the other is based in lucid and objective rationality—we may begin to glimpse the hidden—perhaps the better word is disguised—ritual content of secular ceremonies.

We can also appreciate the ideological force of a cultural experience that claims for its truths the status of objective knowledge. To control a museum means precisely to control the representation of a community and its highest values and truths. It is also the power to define the relative standing of individuals within that community. Those who are best prepared to perform its ritual—those who are most able to respond to its various cues—are also those whose identities (social, sexual, racial, etc.) the museum ritual most fully confirms. It is precisely for this reason that museums and museum practices can become objects of fierce struggle and impassioned debate. What we see and do not see in art museums—and on what terms and by whose authority we do or do not see it—is closely linked to larger questions about who constitutes the community and who defines its identity.

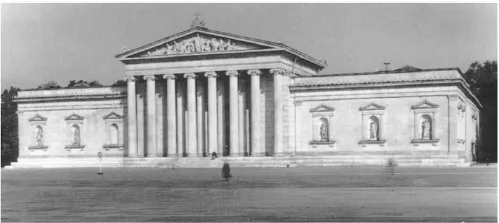

Figure 1.1 Munich, the Glyptothek (photo: museum).

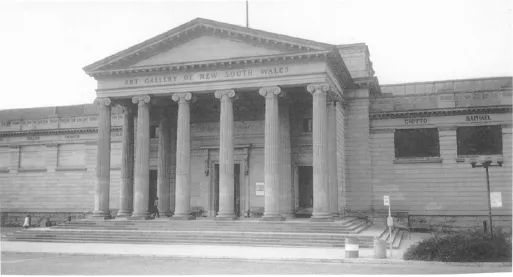

Figure 1.2 The National Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (photo: author).

I have already referred to the long-standing practice of museums borrowing architectural forms from monumental ceremonial structures of the past (Figures 1.1, 1.2, 4.13). Certainly when Munich, Berlin, London, Washington, and other western capitals built museums whose facades looked like Greek or Roman temples, no one mistook them for their ancient prototypes. On the contrary, temple facades—for 200 years the most popular source for public art museums4—were completely assimilated to a secular discourse about architectural beauty, decorum, and rational form. Moreover, as coded reminders of a pre-Christian civic realm, classical porticos, rotundas, and other features of Greco-Roman architecture could signal a firm adherence to Enlightenment values. These same monumental forms, however, also brought with them the spaces of public rituals—corridors scaled for processions, halls implying large, communal gatherings, and interior sanctuaries designed for awesome and potent effigies.

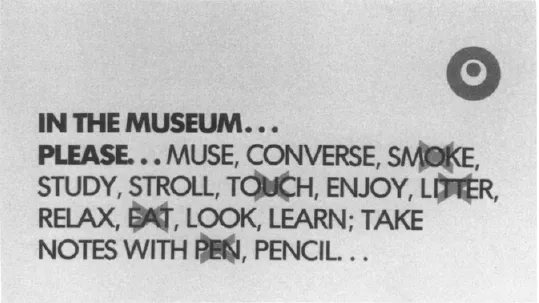

Figure 1.3 Instructions to visitors to the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC (photo: author).

Museums resemble older ritual sites not so much because of their specific architectural references but because they, too, are settings for rituals. (I make no argument here for historical continuity, only for the existence of comparable ritual functions.) Like most ritual space, museum space is carefully marked off and culturally designated as reserved for a special quality of attention—in this case, for contemplation and learning. One is also expected to behave with a certain decorum. In the Hirshhorn Museum, a sign spells out rather fully the dos and don’ts of ritual activity and comportment (Figure 1.3). Museums are normally set apart from other structures by their monumental architecture and clearly defined precincts. They are approached by impressive flights of stairs, guarded by pairs of monumental marble lions, entered through grand doorways. They are frequently set back from the street and occupy parkland, ground consecrated to public use. (Modern museums are equally imposing architecturally and similarly set apart by sculptural markers. In the United States, Rodin’s Balzac is one of the more popular signifiers of museum precincts, its priapic character making it especially appropriate for modern collections—as we shall see in Chapter 5.5)

By the nineteenth century, such features were seen as necessary prologues to the space of the art museum itself:

Do you not think that in a splendid gallery…all the adjacent and circumjacent parts of that building should…have a regard for the arts, … with fountains, statues, and other objects of interest calculated to prepare [visitors’] minds before entering the building, and lead them the better to appreciate the works of art which they would afterwards see?

The nineteenth-century British politician asking this question6 clearly understood the ceremonial nature of museum space and the need to differentiate it (and the time one spends in it) from day-to-day time and space outside. Again, such framing is common in ritual practices everywhere. Mary Douglas writes:

A ritual provides a frame. The marked off time or place alerts a special kind of expectancy, just as the oft-repeated ‘Once upon a time’ creates a mood receptive to fantastic tales.7

“Liminality,” a term associated with ritual, can also be applied to the kind of attention we bring to art museums. Used by the Belgian folklorist Arnold van Gennep,8 the term was taken up and developed in the anthropological writings of Victor Turner to indicate a mode of consciousness outside of or “betwixt-and-between the normal, day-to-day cultural and social states and processes of getting and spending.”9 As Turner himself realized, his category of liminal experience had strong affinities to modern western notions of the aesthetic experience—that mode of receptivity thought to be most appropriate before works of art. Turner recognized aspects of liminality in such modern activities as attending the theatre, seeing a film, or visiting an art exhibition. Like folk rituals that temporarily suspend the constraining rules of normal social behavior (in that sense, they “turn the world upside-down”), so these cultural situations, Turner argued, could open a space in which individuals can step back from the practical concerns and social relations of everyday life and look at themselves and their world—or at some aspect of it—with different thoughts and feelings. Turner’s idea of liminality, developed as it is out of anthropological categories and based on data gathered mostly in non-western cultures, probably cannot be neatly superimposed onto western concepts of art experience. Nevertheless, his work remains useful in that it offers a sophisticated general concept of ritual that enables us to think about art museums and what is supposed to happen in them from a fresh perspective.10

It should also be said, however, that Turner’s insight about art museums is not singular. Without benefit of the term, observers have long recognized the liminality of their space. The Louvre curator Germain Bazin, for example, wrote that an art museum is “a temple where Time seems suspended”; the visitor enters it in the hope of finding one of “those momentary cultural epiphanies” that give him “the illusion of knowing intuitively his essence and his strengths.”11 Likewise, the Swedish writer Goran Schildt has noted that museums are settings in which we seek a state of “detached, timeless and exalted” contemplation that “grants us a kind of release from life’s struggle and…captivity in our own ego.” Referring to nineteenth-century attitudes to art, Schildt observes “a religious element, a substitute for religion.”12 As we shall see, others, too, have described art museums as sites which enable individuals to achieve liminal experience—to move beyond the psychic constraints of mundane existence, step out of time, and attain new, larger perspectives.

Thus far, I have argued the ritual character of the museum experience in terms of the kind of attention one brings to it and the special quality of its time and space. Ritual also involves an element of performance. A ritual site of any kind is a place programmed for the enactment of something. It is a place designed for some kind of performance. It has this structure whether or not visitors can read its cues. In traditional rituals, participants often perform or witness a drama— enacting a real or symbolic sacrifice. But a ritual performance need not be a formal spectacle. It may be something an individual enacts alone by following a prescribed route, by repeating a prayer, by recalling a narrative, or by engaging in some other structured experience that relates to the history or meaning of the site (or to some object or objects on the site). Some individuals may use a ritual site more knowledgeably than others—they may be more educationally prepared to respond to its symbolic cues. The term “ritual” can also mean habitual or routinized behavior that lacks meaningful subjective context. This sense of ritual as an “empty” routine or performance is not the sense in which I use the term.

In art museums, it is the visitors who enact the ritual.13 The museum’s sequenced spaces and arrangements of objects, its lighting and architectural details provide both the stage set and the script—although not all museums do this with equal effectiveness. The situation resembles in some respects certain medieval cathedrals where pilgrims followed a structured narrative route through the interior, stopping at prescribed points for prayer or contemplation. An ambulatory adorned with representations of the life of Christ could thus prompt pilgrims to imaginatively re-live the sacred story. Similarly, museums offer well-developed ritual scenarios, most often in the form of arthistorical narratives that unfold through a sequence of spaces. Even when visitors enter museums to see only selected works, the museum’s larger narrative structure stands as a frame and gives meaning to individual works.

Like the concept of liminality, this notion of the art museum as a performance field has also been discovered independently by museum professionals. Philip Rhys Adams, for example, once director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, compared art museums to theatre sets (although in his formulation, objects rather than people are the main performers):

The museum is really an impresario, or more strictly a régisseur, neither actor nor audience, but the controlling intermediary who sets the scene, induces a receptive mood in the spectator, then bids the actors take the stage and be their best artistic selves. And the art objects do have their exits and their entrances; motion—the movement of the visitor as he enters a museum and as he goes or is led from object to object—is a present element in any installation.14

The museum setting is not only itself a structure; it also constructs its dramatis personae. These are, ideally, individuals who are perfectly predisposed socially, psychologically, and culturally to enact the museum ritual. Of course, no real visitor ever perfectly corresponds to these ideals. In reality, people continually “misread” or scramble or resist the museum’s cues to some extent; or they actively invent, consciously or unconsciously, their own programs according to all the historical and psychological accidents of who they are. But then, the same is true of any situation in which a cultural product is performed or interpreted.15

Finally, a ritual experience is thought to have a purpose, an end. It is seen as transformative: it confers or renews identity or purifies or restores order in the self or to the world through sacrifice, ordeal, or enlightenment. The beneficial outcome that museum rituals are supposed to produce can sound very like claims made for traditional, religious rituals. According to their advocates, museum visitors come away with a sense of enlightenment, or a feeling of having been spiritually nourished or restored. In the words of one well-known expert,

The only reason for bringing together works of art in a public place is that… they produce in us a kind of exalted happiness. For a moment there is a clearing in the jungle: we pass on refreshed, with our capacity for life increased and with some memory of the sky.16

One cannot ask for a more ritual-like description of the museum experience. Nor can one ask it from a more renowned authority. The author of this statement is the British art historian Sir Kenneth Clark, a distinguished scholar and famous as the host of a popular BBC television series of the 1970s, “Civilization.” Clark’s concept of the art museum as a place for ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Art Museum as Ritual

- 2 From the Princely Gallery to the Public Art Museum

- 3 Public Spaces, Private Interests

- 4 Something Eternal

- 5 The Modern Art Museum

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography