![]()

1

PUTTING YOUNG PEOPLE IN

THEIR PLACE

I begin this book with two stories that contextualize some of my interests in children’s geographies. Although personal, I want to suggest that these stories reflect, as least in part, aspects of a recent sea-level change in ways social scientists encounter young people and theorize the fields of childhood and adolescent study. The first story takes place in a children’s museum in Canada when I was a doctoral candidate; the second occurred in Mexico City about a year after I finished my PhD. They are stories about encounters with children but they are epiphanal because they changed, at an indistinct but fundamental level, how I think about young people and their place in the world. I present them here to first help establish some preliminary images for what I want to talk about in the balance of the book. They also enable me to think more clearly about how social science in general, and geography in particular, has in recent years come to know children in a critical and generous way. These new ways of knowing, as I see them, encompass an increased reflexivity between adult researchers and younger participants, they propel concerns about the discourses of science and nature within which childhood and adolescence fitfully repose, and they engage sensitive issues about the ways young people compose their identities. They also broaden scales of concern beyond children and their families with appropriate critiques of globalization, citizenship, young people’s rights and the moral relations between young and old. The second part of this introductory chapter details this critique, and lays out a basis for some of the arguments I make in the rest of the book. Taken from these changes in how we come to know children and their place in the world, my arguments suggest a moral imperative to reconsider critically children’s spaces as personally and politically embodied and locally embedded, and as a harbinger for new ways of understanding development.

Encountering young people 1: the cave

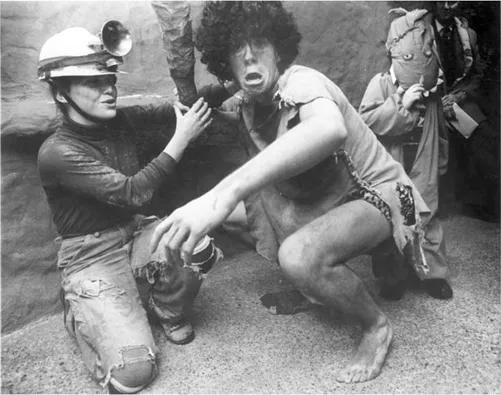

I sit on the plaster ledge of a simulated cave in a museum and scratch vigorously under my arm (the simulated animal skins are a bit itchy) before swinging onto the floor and busying myself with some bones strewn across the floor. I pile the bones up and then, unsatisfied, pull them apart before taking some pains to balance two or three of them in what I think is quite an interesting sculpture. My back is to the entrance of the cave enabling me to satisfactorily ignore my handler’s entreaties to come and meet some new visitors. My handler, Lisa, is a spelunker, replete with hard hat and carbide lamp. Lisa is a real caver and a qualified museum interpreter who helps young children understand what it is like to live in caves. I am not a real caveman nor am I an interpreter, but today I am an important prop in Lisa’s exhibit. She has brought a small group of young children (the oldest looks about five) to meet “Urg.” That’s me, it is an eponymous title because it is all I say. It is part of my performance as a 4,500 year old cave dweller.

Figure 1.1 Stuaft-the-caveman

Source: Photo Archive for The London Free Press, J.J. Talman Regional Collection, D.B. Weldon Library, University of Western Ontario. Reprinted with permission

Earlier that year Lisa and I were with a group of cavers exploring Blowing River Cave in Tennessee. Preserved in the mud of this cavern are footprints of nine explorers (five men, two women and one child) who were probably looking for mineral salts. Here was an intrepid group of adults and a child exploring the reaches of a dark and inhospitable environment. Radio carbon dating of scattered charcoal believed to be from torches used by these early explorers dates their trip to around 2,500 BC. We used carbide lamps and two back-up sources of light. As I sat on a ledge in Blowing River with Lisa, I rustled my bag with extra carbide and wondered if those early explorers – if that is what they were – worried whether they had brought enough reeds for their torches. We discussed the immense feat of coming this far back into a cave with only reed torches and speculated on the possibility of another entrance. The winds of the cave suggested that if such an entrance had existed, it was long ago sealed by earth movements. We decided that a venture this far into the cave was near impossible without contemporary equipment. As I scurried along their route carefully avoiding the areas where footprints remained I wondered if the child felt the thrill of exploring places where few people dared go or if this for her was a common occurrence. I wondered at the arrogance of transferring my excitement, wonder and fear onto a child from 4,500 years ago whose footsteps I followed.

It is not my imagining of that neolithic child’s story or my adventures in Blowing River that I want to relate here, but the “Urg” event that followed shortly thereafter. It is an event that none the less relates to the way I imagine relations with children. Some members of our trip decided to build a cave in the children’s museum where Lisa worked. The cave boasted simulated limestone formations, rooms, crickets, bats and tight squeezes suitable for the passage of only the smallest bodies. Lisa developed an interpretative program and I volunteer to spend the weekend as Urg. The cave exhibit is “hands on” and I am to be played with.

The five youngsters cower behind Lisa as they enter the room of the cave where I am playing with the bones. Their parents and a newspaper photographer come in behind them. Lisa calls to me and I sniff the air. Then I slowly turn to face my audience. I can see that the children are interested in me but are too nervous to leave Lisa’s protection. The photographer’s camera flashes and I startle. Feigning terror in the face of this unknown disturbance, I scamper to the back of the cave and cringe behind a fake limestone formation. For some reason, my actions embolden two of the children who tentatively approach me and, taking my hand, lead me back into the center of the room. I am crouching at about the children’s height as one throws her arms around my neck as if to ward off the advances of the photographer. The ensuing photo-opportunity is spoiled by another child who scolds the photographer for trying to frighten me. And suddenly I am theirs: Lisa and parents are forgotten as the children surround me with affectionate touches and protective body language.

I am not sure what I became in that simulated cave in my simulated animal skins – a pet, a plaything, a confidant, an ally against adults – but for the next half hour I felt like I was a trusted part of the world of those children. We played with the bones and then they took me out of the cave and showed me the rest of the museum. They explained how coke machines worked and that the frightening skeleton of an Albertosaurus wouldn’t hurt me. They showed me some of the museum’s exhibits and explained how they should be used. They got a kick out of using me to scare adults. I realized why the people in Goofy and Mickey suits at Disneyland have so much fun. I wondered if I, like the Disney characters, was simply another commodified pretext for what should fill a child’s world. I was an adult construction of new ways that children should learn – hands-on, festive, fun, playful – about worlds that certainly did not exist the way we were portraying them. But there was something different here that went beyond education, museums or Disney. I was part of the play of children and their trust enfolded me in an enticing and carefree space of belonging. It was as if, by doing nothing of any great importance, we were doing the most important thing that the particular moment enabled. When the children reluctantly left I went back to my cave and waited eagerly for the next group.

My encounter with those young children is an indelible part of how I now approach the study of children. At the time of my museum performance I was beginning a dissertation that drew in part from cognitive behavioral geography. It was the early 1980s and prevailing methods for studying children were heavily influenced by Piaget’s theorizing that children invariably experienced life through a structured series of developmental stages. Geographers used standard Piagetian bench tests, and developed sketch mapping and wayfinding exercises along with aerial photograph interpretation to help them establish the spatial efficacy of developmental stages. As interesting as these studies are, my encounters with children such as those in the cave suggested something more was needed to gain a broader understanding of children’s geographies. The Piagetian paper and pencil tests seemed too far removed from children’s lived experiences and they problematically positioned the researcher as an objective, impartial assessor of how well children performed. I found it quite disturbing that many of the papers on children’s mapping and wayfinding abilities cited as inspiration Edward Tolman’s (1948) work on “cognitive maps in rats and men.” At the time I was less concerned about the bestial and sexual metaphors than the precise rationale and processes suggested by the model of learning and development espoused in these works. As I performed Urg in that simulated cave, I was engaging with children in a very serious enterprise and I knew that their worlds and their sense of wonder could not be understood through simulations and tests. The mapping metaphors were problematic because they challenged a seemingly sacred space and reduced it to the same kind of Euclidean dimensionality that found its most poignant applications in warfare and colonial expansion. It seemed to me that an agent of imperial conquest might well constitute an inappropriate tool for engaging young minds. My feelings about children’s sketch maps rested fitfully against my training in cartography, but they came at a time of new maps, new geographies and new ways of thinking about space.

An understanding of maps wasn’t the only thing to change in the 1980s. An epistemological and moral sea-level change swept many disciplines in the social sciences onto uncharted territories where traditional techniques and understandings precipitated inadequate and undesirable encounters with young people. Theories and methods assumed to be unassailable during my years in graduate school no longer retained any kind of solid semblance. Some of us became unsure of how to approach our subjects, and even less clear about how to situate ourselves in what we studied. We did not want to be distant, impartial laboratory technicians or objective field researchers who used metaphors of rat behavior and cognitive maps to understand children and their worlds.

A much heralded “crisis of representation” un-moored academic practices of writing and this crisis became particularly appropriate for understanding where we situate ourselves in relation to young people (Yuval-Davis 1993; Stephens 1995). Terms such as “children” and “youth,” heretofore thought unproblematic, became sources of significant debate (Griffin 1993). Are they naturalized as the lower (less than) part of a developmental sequence? Why is the term “kid” acceptable to some youngsters while “child” suggests different connotations? At what age does childhood begin and end? How do we come to know adolescence? In contemporary usage there is constant slippage between the terms that characterize young people. Sometimes, as in the case of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and The International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC), the term child is used to describe all people under eighteen years of age. In other contexts child is used to describe pre-pubescent young people, with terms such as adolescent or teenager used to describe older children. At one level, the state defines entry into adulthood but, at other levels of culture and commerce, there is a homogenization of symbols to the extent that it is difficult to know where the child ends and the adult begins. For some, being a child is opposite to being an adult, and this conceptualization is sometimes extended to suggest that childhood is simply the absence of adulthood. For others there is recognition of the particular qualities of childhood, but this is tempered by the belief that with maturity come distinct improvements. This is certainly the case with spatial cognition and developmental theories, which suggest that through certain stages children gain the maturity to handle more complex environments and ways of knowing.

The concepts of childhood and adolescence are necessarily linked to that of adulthood but adolescence complicates these webs of meaning. The widespread use of this term is relatively new, and the fact that it is regarded as an appropriate category for scientific study may be attributed to the influential work early this century of Granville Stanley Hall (1904). But today most academics recognize that distinctions between children, teenagers and adults are politically contrived. Gill Valentine, Tracey Skelton and Deborah Chambers (1998, 4) point out that much of the scientific concern derives from “anxiety about the undisciplined and unruly nature of young people (particularly working class youth) [that] has been repeatedly mobilized in definitions of youth and youth cultures for over 150 years.” Indeed, Valentine (1996, 582) notes that in interviews with parents about issues of safety, many frequently “elided their discussions of the under 12s and teenagers when talking about ‘dangerous children.‘” Sharon Stephens (1995, 13) argues that although there is a growing consciousness of children at risk, there is also a growing sense of children as the risk. In stories of street-children from Rio de Janeiro to Los Angeles, children are represented as malicious predators who are unshackled from moral and social responsibilities. Recent research suggests larger institutional and societal constraints, and a quixotic search for identity by those who are young and homeless. Harriott Beazley (2000, 2001), for example, identifies “geographies of resistance” in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, where a response to the larger “spatial apartheid” of the State empowers street-children. In her study of seemingly dangerous youth in Los Angeles, Sue Ruddick (1995, 1998) argues that terms such as delinquent, punk and runaway are conflated in apodicitic geographies that disenfranchise homeless young people from the spaces that serve their identity needs. That this crisis takes place simutaneously in Yogyakarta and in Los Angeles is an important point. As Stephens (1995, 8) points out, the “[c]urrent crises in notions of childhood, the experiences of children, and the sociology of childhood are related to profound changes in a now globalized modernity in which the child was previously located.” Children experience the world as it is manifest, and they are part of the ideology, war and corporate greed that is exported from the boardrooms and strategic command centers of Washington, Paris and London. It is within this context that I place the photograph on this book’s paperback cover. Taken by a friend of mine who worked in northern Nicaragua during the Sandanista revolution, it depicts two boys “doing nothing of any great importance” in a highly politicized global space. It is a space that was contorted by greed, ideology and racism. Contras looking for a leftist priest days previously had attacked the boys’ village. The boys hang out for a moment while the village cringes before the possibility of another attack. Mean streets, war zones, public kid corrals and private family realms of child abuse. These spaces are the places of children, and they embody the pretensions of our adult sexed, raced, politicized and able-bodied selves.

The plasticity of terms such as child and adolescent begs for more nuances than offered by traditional educational and developmental theories. The reason for this need, I would argue, is because of the moral turpitude that is embedded in changing conceptualizations of young people. Distinguishing children as non-adults or young people is also unsatisfactory because it establishes a simplistic binary and directs attention away from children’s daily lives by emphasizing what children lack before becoming adults. The fluidity of terms to describe kids and teens seems appropriate to their shifting identities and so I make no excuses for, indeed I make a point of, slipping between concepts such as infant, toddler, youth, child, adolescent and teenager. I do so not to denigrate the important differences between toddlers and adolescents but to point out the baggage (and disempowerment) that is associated with these terms. What particular kind of bodily comportment does the term toddler suggest? What does it mean, for example, to call a 13-year-old a teenager, a gangly youth, an adolescent or a pubescent child?

Nor am I suggesting with a focus on those who are “not adults” that a universal category of experience exists. Although children are defined in relation to adults, as Holloway and Valentine (2000b, 6) point out “other differences also fracture (and are fractured by) these adult–child relations.” Children grow into the pretension of identities that reflect race, class, gender, bodily appearance and other socially constructed differences. These axes of difference are not singular or additive but they constitute rather multiple transgressive and transformative features of identity. My calling upon a series of “adult, Western views” in this book may suggest an essential and universal notion of “the child,” or that children are passive in creating their identities and that their lives can only gain meaning through adult values. This is clearly not the case, but perhaps it is worthwhile thinking of the terms used to describe young people as parasitic because they often inculcate children as research subjects, or as part of the family realm, or they commodify their desires into a form that garners maximum profit for global corporations. This book is about the social construction of young people through time and in space. It is about the Western ideological construction of childhood as a privileged private domain of innocence, spontaneity, play, freedom and emotion in opposition to a public culture of culpability, discipline, work, constraint and rationality. There is a growing body of work on Western childhood suggesting the creation and expansion of the modern antimony of child/adult, like the female/male dichotomy, is crucial to setting up hierarchical relations upon which modern capitalism and the modern nation-state depends (Postman 1982; Qvortrup 1985; Stephens 1995). In what sense does this antimony help engender a status quo that reduces the lives and practices of young people to something from which corporations can profit? Put another way, how are the constraints on young people’s lives also about how to make adult lives more comfortable?

Concerns about how the lives of young people are constrained by contemporary Western values are sometimes paralleled in social science research by how they are othered. Characterizing young people as other is a particularly thorny problem. Of all people who are constituted as other in that they are different from us, young people are particularly perplexing because they are intimately part of our lives and they are, at least in part, constituted by what we are and what we do. Perhaps this is why children are not always “othered” with the same exclusionary ferocity that permeates some discourses on women or people of color but, rather, they are openly valued (Holloway and Valentine 2000b, 4). To add to the problem, adults all used to be young and are sometimes predisposed to make claims about knowing what the lives of young people are about. What biographical baggage do we, as researchers and adults, bring to the study of children and youths? To what extent can our adult position invalidate our ability to empathize and situate ourselves authentically in the lives of children? Children see things in environments that we may have forgotten how to see, let alone understand. If we can no longer fully empathize with young people or imagine what they experience, how can we write for them and establish agendas on their behalf? How do we perform our lives and our research arou...