- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

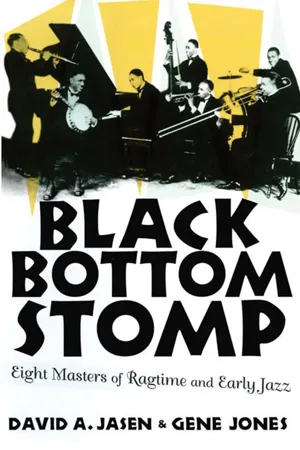

Black Bottom Stomp tells the compelling stories of the lives and times of nine seminal figures in American music history, including Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong, and Jelly Roll Morton.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Bottom Stomp by David A. Jasen,Gene Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

SCOTT JOPLIN

COTT JOPLIN WAS in the netherworld of itinerant black pianists of his day, but he was not of it. He was somehow different from his compatriots, and everyone who knew him thought so. Even as he was scrounging for a living in midwestern saloons, as his friends were doing, and selling his work for the same paltry fees that they were getting, Joplin stood apart. He was quiet, intense, cool. He seemed to know something, to want something, to have his eye on something that his contemporaries could not see.

What Joplin knew was that ragtime, despite its seedy origins and the frivolous uses to which it was put, was important. While most black pianists of the mid-1890s saw the music solely as a way of making a living, Joplin saw it as a new American art. What he wanted was respect: for his music, for himself, and for his race. He envisioned a music that could erase the lines between high and low culture, that used all of what America had to offer. He was willing to extend himself to realize this vision, to learn as well as to teach.

Joplin was a serious musician and a serious person, but he was not a crank, a martinet, or a martyr. He never wrote down to his audience, and, even more important, he never sacrificed the joy of ragtime on the altar of “art.” There are “serious” Joplin rags, but there are no gloomy or selfindulgent ones. His thirty-eight published rags are beacons that cut through the gaslight of his era to illuminate many kinds of music that came after them. Since the publication of “Maple Leaf Rag,” Joplin’s mastery has been unassailable. He had the greatest command of syncopated melody, and he produced more great rags than anyone else.

Scott Joplin was born on November 24, 1868, in Bowie County, in the northeast corner of Texas. His father, Giles Joplin, had been a slave, and at the time of Scott’s birth, Giles was trying to scratch out a living as a backwoods farmer. Giles and Florence Joplin moved their family to Texarkana, Arkansas, a town of about three thousand that had lately sprung up to straddle the line between the two states implicit in its name. Giles got a job there as a laborer on the Texas & Pacific Railroad line, and Florence worked as a laundress and cleaned houses.

Their Texarkana neighbors remembered the entire Joplin family (with four sons and two daughters by then) as being musical. Giles played the fiddle, as he had for plantation dances in North Carolina, and Florence sang and accompanied herself on the banjo. All the children sang too, and Giles and Florence taught them fingerings on the fiddle, banjo, and guitar. Such portable—and sometimes homemade—instruments were usually the only ones that rural black children of the early Reconstruction era could obtain, but when Scott was about seven, he made a marvelous discovery. He went with his mother to clean the house of a white lawyer, W. G. Cook, and there he saw, and was allowed to play, a piano.

Joplin took to it at once, and he showed enough aptitude to prompt his parents to scrimp a bit to pay for lessons. He studied with several Texarkana teachers, but his main teacher was a German immigrant named Julius Weiss. Weiss, a tutor for a white family’s children, gave young Scott free lessons and introduced him to the European classics. Giles Joplin left his family in the early 1880s, but Florence, with her household income pinched by her husband’s departure, managed to put aside enough money to buy Scott a secondhand piano.

When he was about sixteen, Scott Joplin organized a vocal quartet— himself, his brother Will, and two neighbor boys—to sing at church socials and parties in Texarkana and surrounding towns. Then, with only the experience of playing for his neighbors and singing for northeast Texas and southwest Arkansas churchgoers, Scott Joplin left home to become a professional musician.

His wanderings cannot be precisely tracked through these early years. Like dozens of other young black men starting out in music then, Joplin played where he could. We can pinpoint him only occasionally, in announcements from small-town newspapers and through the recollections of his friends. And it is obvious from these glimpses of him—a brief appearance with a Texarkana minstrel troupe in 1891, a stint at “Honest John” Turpin’s Silver Dollar Saloon in St. Louis—that he was, like all the rest, improvising a career. Joplin was based at the Silver Dollar for several years in the late ’80s and early ’90s, but he worked out from St. Louis, too, all over the Mississippi Valley.

In 1893 the Columbian Exposition, which everyone called the “World’s Fair,” opened in Chicago. (It was organized to celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to America, but it was a year late in preparation.) The fair drew many black singers, pianists, and bands to Chicago, all of them hoping for work in the saloons and houses that fringed its grounds. Brun Campbell, a white ragtimer who studied under Joplin, said that his teacher was among the wandering musicians who went to Chicago then. Joplin supposedly organized a small band there and played in several places around the city, but there is no evidence that he (or any other rag player) performed at the fair itself. It is interesting to speculate about what Joplin may have played and whom he may have heard there, but, like most of his early professional life, his months in Chicago are lost to us.

By 1894 Joplin was back in St. Louis, once again a mainstay at the Silver Dollar. It was around this time that he met John Turpin’s sons, Charlie and Tom, who had recently returned from a year or so of mining in the West. Although their playing styles were poles apart, the bombastic Tom Turpin and the introspective Joplin became good friends. This friendship would sustain Joplin a few years later, during the most difficult period in his life.

For some reason, Joplin chose to settle in Sedalia, Missouri, in the mid-’90s. This west-central town was much smaller than St. Louis, and its size may have suited Joplin better. For a small town, Sedalia had an active musical life, which also could have attracted him. There were about three dozen saloons, as well as dancehalls, whorehouses, and gambling rooms, strung along Main Street, and there were several semiprofessional concert and choral groups in town, black and white. There was also a newly opened school for blacks, George R. Smith College, which probably played a role in luring Joplin to the town. At first Sedalia was just another temporary base for Joplin, a place to work out of and return to, but he would soon become an integral part of the town’s musical scene.

Scott Joplin organized a singing group in Sedalia, called the Texas Medley Quartet (actually an octet of male voices), in late 1894 or early 1895. There is no record of the group’s touring schedule, but it may be assumed that their travels took them as far as New York and Texas, because Joplin s first published music came from these states during this time. First there were two songs, issued in Syracuse, New York, in 1895; then three instrumentals (two marches and a waltz), published in Temple, Texas, in 1896. There is no hint of brilliance in these early works. The songs are sentimental period pieces, no more musically interesting than a hundred others of their kind. Joplin’s first instrumental, “The Crush Collision March,” is a curious piece of program music, depicting two trains crashing into each other. The score is noted as describing “noise of the trains while running at the rate of sixty miles per hour,” the “whistle before the collision,” and the collision itself.

Back in Sedalia after the octet’s tours, Joplin became a sometime member of the town’s Queen City Cornet Band, but he left this band to form his own. He added to his income by giving piano lessons. One of his students was Arthur Marshall, the teenage son of the family with whom Joplin was boarding. Another was a young man named Scott Hayden. Both of these students would become their teacher’s friends and collaborators. Although the college records are lost, it is believed that both Joplin and Arthur Marshall attended Smith College for a year or so in 1896 or 1897. At any rate, Joplin was becoming a Sedalian.

Late in 1898 The Maple Leaf Club, a new social club for blacks, opened in a second-floor room at 121 East Main Street. Scott Joplin was the “house man” there, and he was billed on the club’s business card simply as “The Entertainer.” The Maple Leaf Club was not as raunchy as most of its Main Street neighbors, but it was noisy enough for local black pastors to disapprove of it (they called it a “loafing place” in an open letter of protest sent to the Sedalia papers).

As a result of his new job, Joplin was becoming a specialist in ragtime. He wrote a handful of rags (perhaps including the one that would become known as “Maple Leaf Rag”) and showed them at the office of A. W. Perry & Sons, a Sedalia publisher. When Perry passed on them, he took them to the Carl Hoffman Music Company in Kansas City. Hoffman’s clerk and arranger, Charles N. Daniels, liked one of the pieces, and in March 1899 Hoffman issued Joplin’s “Original Rags.” Although it was Joplin’s first published rag, it is the work of a composer who knew precisely what he was doing. “Original Rags” is effortlessly melodic, and it is highly sophisticated in its use of syncopations.

In the summer of 1899, John Stark, a white man who owned a Sedalia music store, heard “Maple Leaf Rag” and decided to publish it. Arthur Marshall said that Stark dropped into the Maple Leaf for a beer and heard Joplin playing it; Stark’s son and partner, Will, said that Joplin demonstrated the rag for Stark at their music store. Will’s version seems more likely, but, however it happened, Stark bought the rag and issued it in September. Each was new at the game, so Joplin had the temerity to ask for a penny-a-copy royalty agreement, and Stark knew no better than to give it to him. Because of this dual investment in the work, the success of “Maple Leaf Rag” would change the lives of its composer and its publisher.

The first buyers of “Maple Leaf Rag” were, of course, people in the Sedalia area who had heard Joplin play it. This was always the way with regional publications, and the story usually ended there. There would be a few dozen local sales—rarely more than a hundred or so—and then nothing. “Maple Leaf Rag” reversed the pattern by selling more and more as time went on. After many of the initial printing of four hundred copies were destroyed by a fire in the Stark storeroom in October 1899, Starks perpetual series of reprints began. By 1905, it was selling three thousand copies a month, and it was well on its way to becoming the world’s most popular rag, the one that would stay in print and be recorded in every decade after its publication.

“Maple Leaf” is an exhilaration to play as well as to hear. It is extraordinarily pianistic, masterful in its structure and rhythmic invention, and loaded with devices to make the listener smile and tap the feet. The first of its four sixteen-measure strains is a short course in ragtime all by itself. Forgoing the conventional four- or eight-bar introduction, a one-note pickup begins the piece. Syncopation leaps out from the very first measure, and a parade of raggy rhythms is under way. Measure 9 begins with a marchlike, on-the-beat figure that can’t wait for measure 10 (DA-DA-DA-da-DAA), and this pounce across the bar line moves American music from old-fashioned to newfangled in the blink of an eye. The second strain bubbles with joy, and the third builds excitement with a two-note Charlestonlike figure that is raised by a tone when it recurs. The fourth strain has a strutting, “going home” feel that is enormously satisfying. “Maple Leaf” became the rag that every player wanted to learn, and it has remained the one that listeners have never tired of hearing.

John Stark, at age fifty-eight, found himself the surprised owner of the hottest copyright in ragtime. The adrenaline produced by the sales of “Maple Leaf Rag” flew through its composer and his publisher. Although he was completely unmusical, John Stark honestly loved ragtime, and he decided to commit himself to this new music, to specialize in its publication. In a daring leap, he moved his company and his family to St. Louis in the summer of 1900, eager to swim in the larger pond of commercial music there. Scott Joplin, seeing a bit of financial security in the offing, asked the widowed sister-in-law of his student Scott Hayden to marry him. Belle Hayden accepted the proposal, and the Joplins, joined by Scott Hayden and his wife, Nora, followed Stark out of Sedalia to St. Louis. The two couples shared a rented house at 2658A Morgan Street (now Delmar Boulevard), on the northwest edge of Chestnut Valley.

Joplin returned to St. Louis to find the city aroar with ragtime, and to find himself, as the composer of “Maple Leaf,” a local hero. Tom Turpin’s new Rosebud Bar was the center of the action, and piano playing

JOPLIN’S ST. LOUIS HOME.

was a blood sport there. Day and night Louis Chauvin, Sam Patterson, and Joe Jordan spelled each other at the Turpin piano, in ferocious displays of noise and speed. Joplin knew better than to compete in such company. He had earned his living at the piano for years, but this kind of fierce, show-off playing was beyond him. Others could embellish his “Maple Leaf,” play it hotter and faster, but he was the one who had composed it. The young players of St. Louis venerated him.

Although he had only the small royalties from “Maple Leaf” coming in, along with the fees he received from his handful of other publications, Joplin became choosy about his projects, and he chose to get off the treadmill of bar jobs. He wanted to write and to encourage the young talents around him to write. The first two Joplin rags published by Stark in St. Louis (Joplin’s first ragtime works after “Maple Leaf”) were collaborations with his Sedalia students: “Swipesy,” written with Arthur Marshall in 1900; and “Sunflower Slow Drag,” written with Scott Hayden in 1901. Joplin’s own “Peacherine Rag” came next, also published in 1901. If Joplin’s admirers were expecting a romping follow-up to “Maple Leaf,” “Peacherine” must have shocked them with its simplicity. It is a strolling rag, serene and sunny, with a rustic air about it, nothing like Joplin’s rambunctious hit. (After Joplin acquired some of the professional pop writer’s acumen, he would rework “Maple Leaf’s” devices in later rags, such as “Leola,” “Gladiolus,” and “Sugar Cane.”)

Soon after moving to St. Louis, Joplin felt ready to try something beyond the four-theme rag form, but, to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHORS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PRELUDE

- Introduction TOM TURPIN AND THE BIRTH OF RAGTIME

- Chapter One SCOTT JOPLIN

- Chapter Two EUBIE BLAKE

- Chapter Three LUCKEY ROBERTS

- Chapter Four JAMES P. JOHNSON

- Chapter Five WILLIE THE LION SMITH

- Chapter Six FATS WALLER

- Chapter Seven JELLY ROLL MORTON

- Chapter Eight LOUIS ARMSTRONG

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX OF MUSIC TITLES

- GENERAL INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS