- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As with a number of specific areas in the medical professions, the field of personality disorders has experienced a period of rapid growth and development over the past decade. This volume is designed to offer the student, practitioner and researcher with a single source for the most up-to-date research and treatment writing on a variety of specific areas within the field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Personality Disorders by James Reich, M.D., MPH in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Research

Chapter 1

State and Trait in Personality Disorders

Key Teaching Points

- Personality disorders (PDs) are currently defined as disorders where the personality pathology is constant and long lasting.

- There is evidence that there are situations where personality pathology may not be enduring and long lasting. This includes remissions with treatment of an Axis I disorder and longitudinal studies of severe personality disorders where some disorders show considerable improvement.

- Proposed is the concept of state personality disorder (SPD), a disorder characterized by fluctuating personality pathology.

- This disorder has been identified in two separate populations, has been distinguished from its near neighbor disorders, and has a possible biological marker.

- State PD may be clinically important as there is less suicidal ideation in state PD than in trait PD. Identifying state PD would therefore help clinicians better identify patients at risk for suicide.

- State PD may also be clinically important in its effect of worsening the outcome of comorbid Axis I disorders such as anxiety and depression.

Introduction

Personality has in the past been considered to be stable, or at the very least, something that changes slowly over time. However, all clinicians can think of a case where there was personality change on a seemingly more rapid basis. Sometimes this is in relation to treatment, sometimes not. It is to this phenomenon that this chapter addresses itself. I propose the concept of a state personality disorder (SPD). An SPD would be analogous to the concept of state anxiety, a set of symptoms that appear under certain circumstances and that may remit, perhaps in rapid fashion. In state anxiety these are anxiety symptoms, whereas in state personality these would be symptoms we usually think of as being personality symptoms.

Current Status of the Definition of Personality Disorders

Personality disorders have been conceptualized in different ways by different schools of thought. There is not space here to review all the different conceptualizations of personality disorder, but I will mention two of the current major definitions. The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) (DSM-IV) diagnosis of personality disorder is “An enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture” (American Psychiatric Association, 1994 and 2000, pp. 630, 681). The pattern is manifested in two or more of the following areas: cognition, affectivity, interpersonal functioning, and impulse control. The pattern is inflexible and pervasive across a broad range of situations, has an early onset, is stable, and leads to significant distress or impairment.

Personality disorders, according to the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (ICD-10) diagnostic guidelines (World Health Organization, 1992a),

comprise deeply ingrained and enduring behavior patterns, manifesting themselves in inflexible responses to a broad range of personal and social situations. They represent either extreme or significant deviations from the way the average individual in a given culture perceives, thinks, feels, and particularly, relates to others. Such behavior patterns tend to be stable and to encompass multiple domains of behavior and psychological functioning. They are frequently, but not always, associated with various degrees of subjective distress and problems in social functioning and performance.

The DSM-IV does not allow for the possibility of an SPD. The ICD-10 allows for a personality disorder to be created by stress. An enduring personality change is defined as

a disorder of adult personality and behavior that has developed following catastrophic or excessive prolonged stress, or following a severe psychiatric illness, in an individual with no previous personality disorder. There is a definite and enduring change in the individual’s pattern of perceiving, relating to, or thinking about the environment and the self. The personality change is associated with inflexible and maladaptive behavior that was not present before the pathogenic experience and is not a manifestation of another mental disorder or a residual symptom of any antecedent mental disorder. (WHO, 1992a, 1992b).

The ICD-10 definition does not allow for a stress-created personality disorder to reverse itself.

It is clear that much of the current nomenclature does not have a place for the concept of state and trait personality. (Trait personality or trait PD would be the form of personality dysfunction that is stable over time.)

Some Arguments for the Possibility of an SPD

The two official definitions of personality cited above emphasize the concept of the level of personality functioning being stable over time. However, there is no question that measures of personality characteristics can be elevated if measured when the patient is acutely ill with an Axis I disorder. These measures then return to baseline after resolution of the Axis I disorder (Hirschfeld, Klerman, Clayton, Keller, McDonald-Scott, & Larkin, 1983; Ingham, 1966; Kerr, Schapira, Roth, & Garside, 1970; Reich, Noyes, Coryell, & O’Gorman, 1986; Reich, Noyes, Hirschfeld, Coryell, & O’Gorman, 1987; Reich & Noyes, 1987b; Reich & Troughton, 1988). Although the studies just cited vary in their details, the findings are remarkably similar over several decades and in different populations. That is, that patients who are acutely depressed and patients who are acutely anxious score higher on the same measures of personality than when they are not acutely depressed and not acutely anxious. This would represent one possible model for an SPD. These would be symptoms of personality dysfunction which increase or remit in relatively short periods of time. It certainly demonstrates that clinicians can see more rapid changes in personality than would be expected by current definitions of personality disorder.

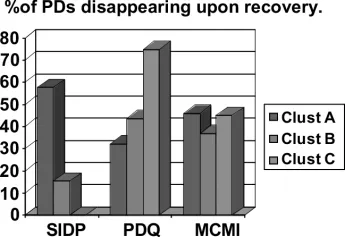

An example of this can be seen in Figure 1.1. Here the prevalence of personality disorders in depressed and recovered patients is used (Reich & Noyes, 1987a; Reich & Troughton, 1988). Personality measures in patients were taken when they were acutely ill and from this was subtracted the prevalence when they were in remission from depression. This results in a picture of the personality disorders that have “disappeared.” As can be seen in the figure for three different personality instruments the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ), the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Personality Inventory (MCMI), and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Personality Disorders (SIDP) (Reich, 1987, 1989) the amount of personality pathology that disappears is large.

Figure 1.1 Effect of state. Clusters A, B, and C refer to personality disorders in the DSM Personality A, B, and C clusters. The first cluster, cluster A or the Schizoid cluster, includes the Schizoid, Schizoptypal and Paranoid personality disorders. The second cluster, cluster B or Impulsive cluster, includes Borderline, Histrionic, Antisocial, and Narcissistic PDs. The third cluster, cluster C or the Anxious cluster, consists of the Avoidant, Dependent, and Compulsive PDs. MCMI, PDQ, and SIDP refer to three different personality instruments, The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ), the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Personality Inventory (MCMI), and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Personality Disorders (SIDP) (Reich 1987, 1989).

One must consider the possibility that this seeming remission of Axis II symptoms with the treatment of an Axis I disorder is a measurement artifact. If this were the case, traits distorted by the presence of an Axis I disorder would have no clinical value (i.e., they would just be “noise” confusing the clinical picture.) However, if the evidence was that SPD can be reliably distinguished from its near neighbors and has important clinical implications, it would clearly be more than noise in the system. The evidence does seem to indicate distinction from near-neighbor disorders and clinical relevance (see sections in this chapter titled “The Disorder Should Be Distinguishable from Its Near-Neighbor Disorders,” and “The Concept Should Have Clinical Relevance”)

Numerous research reports indicate the phenomena of personality pathology being less than life long. Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk (2003) reported a follow-up of patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Thirty-four and a half percent met criteria for remission at 2 years, 44.9% at 4 years, 68.6% at 6 years, and 73.5% over the entire follow-up. Paris and Zweig-Frank (2001) in a long-term follow-up of 64 borderline patients found that for the 15-year follow-up only five met the criteria for borderline personality disorder. In a 7-year follow-up of borderline patients, Links, Heslegrave, & van Reekum (1998) found that only 47.4% still met the criteria for borderline at the end of the study. In a longitudinal study of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive compulsive personality disorders, the majority did not remain at the diagnostic threshold after 12 months (Shea et al., 2004). Seivewright, Tyrer, & Johnson (2002) in a 12-year follow-up of 202 personality disorder patients also came to the conclusion that the assumption that personality characteristics do not change over time is incorrect. The weight of the empirical evidence is that what we have traditionally diagnosed as personality disorders are clearly not as stable as was once thought.

Other Literature Relevant to the State Personality Concept

Other researchers have speculated about the possibility of state-induced personality disorders. As far back as 1968, Leonhard (1968) theorized about this concept. Mischel (1986) examined the issue and found that while high levels of personality traits could predict behavioral response much of the time, when the personality trait was present at lower levels there was more variability in response. Some of this variability was presumed to be environmental. This conceptualization would fit the concept of stress-induced personality disorders. The high trait (trait PD) would be more predictable in their dysfunctional responses, the very low trait (no PD) would have the greatest adaptive flexibility, and the intermediate group (state PD) would be in between. After a review of the literature on personality and anxiety and depressive disorders, Bronisch and Klerman (1991) concluded that an SPD was a reasonable concept. They referred to the concept as “personality change.” They postulated five different areas where fluctuations in personality might occur: mood and affect, impulse control, attitudes toward self, attitudes toward the world, and social and interpersonal behavior.

Other researchers have approached the subject of personality from dimensional and genetic perspectives. Livesley, Jang, Jackson, & Vernon (1993) examined the heritability of personality traits in twin pairs. They found personality traits had varying levels of heritability, some high and some low. They did not see discrete categories of personality, but rather personality traits behaving as dimensionally distributed attributes in the population. For most personality dimensions the best-fitting model specified additive genetic and unique environmental effects. In this model the state personality group would be the middle rank in those who responded to environmental stress. They would be between those who responded maladaptively to minor environmental stress (trait PD) and those who were relatively resilient to environmental stress (no PD.) Although this model would not give clear categorical boundaries, the state personality group would still be of clinical interest.

Tyrer and Ferguson (2000) and Tyrer and Johnson (1996) in the United Kingdom developed an empirically based personality disorder system measured by an instrument called the Personality Assessment Schedule. This system categorizes no personality disorder, subthreshold personality disorder, complex personality disorder, and severe personality disorder. In this system the state personality group might be considered somewhere near the border of subthreshold and the simple personality disorder (Tyrer, personal communication).

Requirements for Validating the Concept of State and Trait Personality Disorders

There are no completely accepted criteria for validating a new psychiatric disorder (Beals et al., 2004). However, the development of diagnostic criteria from other disorders can give us a rough guide. We should be able to distinguish it from near neighbor disorders. We would want it to be associated with an independent measure linking the disorder to its area of hypothesized content. It is useful to have biological, family study, or family history markers. Ideally it should be empirically identified in two or more populations. It should also have clinical relevance.

The Disorder Should Be Distinguishable from Its Near-Neighbor Disorders

No disorder can be considered separate unless it can be distinguished from other disorders with at least some degree of reliability. The ultimate test of this is whether it can be distinguished from its near-neighbor disorders. This does not mean that it does not share symptoms with other disorders, merely that there can be a good differentiation. For example, bipolar disorder and major depression look identical when patients are in the depressed state; however course can distinguish them. Many of the individual personality disorders diagnosed under the DSM system share criteria, but are still considered different constellations of symptoms.

For SPD to meet these criteria it would be necessary to identify groups of patients where there were relatively brief personality fluctuations, and to distinguis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Editor

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I: Research

- Part II: Treatment

- Part III: Trends for the Future

- Index