![]()

1 Introduction

Microbial plant pathogens – oomycetes, fungi, bacteria, phytoplasmas, viruses and viroids – infect crops, weeds and wild plants in all agroecosystems. Microbial plant pathogens induce various types of symptoms, the severity of which may depend on the levels of susceptibility/resistance of the cultivar, virulence of the pathogen species/strains/varieties/isolates, and prevailing environmental conditions. Microbial plant pathogens may be disseminated predominantly via seeds/propagules, soil, irrigation water and wind. Soilborne microbial plant pathogens commonly cause damping-off, stem rot, crown rot and root rot in planta and soft rot in tubers and other storage organs. Sheath blight, foliar or flower blight symptoms may be induced, when infected by the spores released from infected plant debris left in the soil after harvest. Transmission of some soilborne pathogens may also occur through seeds/propagules finding their way rapidly even to distant locations.

1.1 ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF DISEASES CAUSED BY SOILBORNE MICROBIAL PLANT PATHOGENS

Soilborne microbial plant pathogens generally infect hypogeal (belowground) plant organs – crowns and roots, stems, storage organs like tubers and pods in some pathosystems. When the root system is damaged, transport of water and nutrients to the epigeal (aboveground) plant organs is reduced to a different extent, depending on the growth stage of the plants at infection, levels of susceptibility/resistance of the plants, and virulence of the pathogen species, and prevailing environmental conditions. The formation of characteristic lesions on the affected parts and necrosis of the vascular tissues and the ultimate death of the infected plants are commonly observed. Thus, the extent of losses depends on several major factors such as host responses to pathogens, and presence of other pathogens acting synergistically. The term ‘pathometry’, as introduced by Large (1966, refers to the measurement of disease, based on reliable methods of assessment of crop losses, since the magnitude of losses is directly related to disease severity. Disease severity represents the extent of pathogen invasion in the host plants and the amount of host tissues destroyed or made nonfunctional/less functional by the pathogen, resulting in reduction in crop productivity to varying degrees. When soilborne pathogens such as Fusarium oxysporum, Verticillium spp. and Rhizoctonia solani infect the roots, discoloration of leaves (foliage) and loss of flaccidity are observed, indicating the adverse effect on photosynthesis and absorption of nutrition and water and translocation of photosynthates to storage organs. Injury to the crop may be defined as the visual or measurable symptoms induced by pathogens (Gaunt 1995). Disease assessment provides quantitative information required for determining the effectiveness of disease management strategies, surveys for losses and breeding programs to develop disease resistant cultivars.

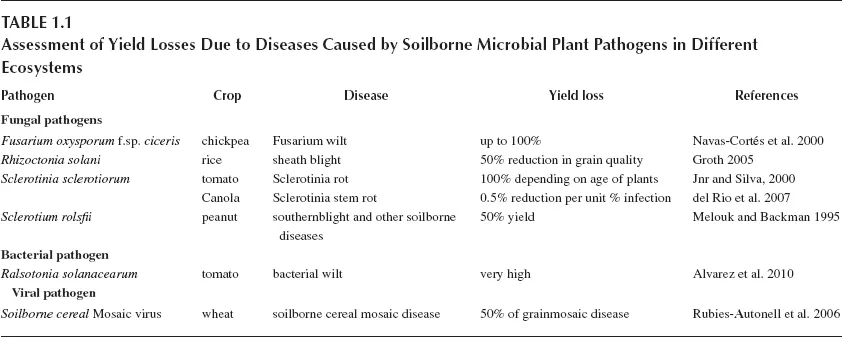

Assessment of losses caused by rice sheath blight (induced by R. solani) and sugar beet rhizomania (caused by Beet necrotic yellow vein virus) was taken up in the earlier years (Cu et al. 1996; Henry 1996). Assessment of losses due to diseases caused by soilborne microbial plant pathogens is generally made by determining the percentages of plants infected out of total number of plants examined. Methods have been developed to assess the disease incidence and severity quantitatively in certain pathosystems. The severity of root damage due to Phytophthora fragariae var. fragariae in strawberry plants was assessed based on the percentage of invaded root tissue (PIRT) showing rotting symptoms, using the light microscope. Based on disease severity assessments, the levels of resistance of strawberry cultivars and genotypes were also determined (Van de Weg et al. 1997). Among the soilborne bacterial pathogens, Ralstoinia solanacearum is more widely distributed and capable of infecting more than 200 plant species. R. solanacearum causes enormous losses in several crops including banana, potato, tomato, groundnut (peanut) and tobacco (Alvarez et al. 2010). Incidence of banana Xanthomonas wilt caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum was observed in 60% of the sites, where banana was grown in 35 districts in Uganda between 2001 and 2007. Production loss was estimated to be about 53% over a ten-year period amounting to between two and eight billion dollars (Tripathi et al. 2009). Different techniques such as image analysis, remote sensing technology and molecular methods have been employed to quantify the extent of tissue damage by soilborne microbial pathogens (Narayanasamy 2002, 2011). The effects of infection by soilborne pathogens have to be assessed using specialized procedures, since the interactions are very complex. It has been found to be difficult to determine the contributions of different factors to disease development. Invasive methods are commonly followed to assess the intensity of root lesions and crown infections by taking samples at different intervals after challenge inoculation. Yield losses have been estimated in various pathosystems to help the taking of appropriate preventive/curative activities to lessen the losses to the extent possible (see Table 1.1).

1.2 CONCEPTS AND IMPLICATIONS OF INFECTION BY SOILBORNE MICROBIAL PLANT PATHOGENS

Soilborne fungal plant pathogens infecting belowground plant organs are classified as root inhabitants or soil inhabitants. Root inhabitants are considered as ecologically obligate parasites. On the other hand, soil inhabitants can exist as saprophytes in the absence of susceptible host plants. The nature of invasive force of the pathogen was redefined and the term ‘inoculum potential’ was suggested as the energy of growth of a parasite available for infection of a host, at the surface of the host organ to be infected. The energy of growth implies the infective hyphae of one sort or other are actually growing out from the inoculum. Root-infecting fungi may be of two types. Unspecialized root-infecting fungi are usually characterized by wide host range, which confers the advantage of abundance and wide distribution upon the parasite. In contrast, specialized parasites have evolved in such a way as to cause minimum possible damage to the functioning of host plant. They may be host-specific and they have discarded the ability to continue as competitive saprophytes. The growth rate of specialized parasites seems to have been much reduced in the absence of susceptible plants. Damping-off and root rot diseases are caused by Pythium spp. and R. solani, which can exist as saprophytes for longer periods on organic matter and become parasitic, when susceptible crops are planted. Vascular wilt fungi F. oxysporum and Verticillium spp. are specialized soilborne pathogens. Saprophytic survival of these pathogens is more due to the formation of sclerotia or chlamydospores remaining viable in soil for long periods (Garrett 1970). The soilborne microbial pathogens are able to infect annuals, as well as perennials. Fungal pathogens infecting annuals may have different modes of survival in the absence of crop hosts: (i) pathogens that survive as sclerotia have a wide host range; (ii) pathogens surviving as resting spores have restricted host range; and (iii) pathogens surviving as mycelium in crop debris may have a somewhat restricted host range. Among the fungal pathogens, Phytophthora spp., Pythium spp., F. oxysporum, Verticillium spp., R. solani and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum have worldwide distribution and are responsible for total crop loss, when susceptible cultivars are grown in large areas and favorable environmental conditions prevail. Bacterial pathogens causing soilborne diseases are less numerous and they include Ralstonia solanacearum, Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicum, Pectobacterium spp. and Streptomyces scabies. Viruses, except for a few, cannot remain infective in a free state in the soil environment. They have to be protected in the body of the vectors. These viruses, transmitted by soilborne fungal or nematode vectors, have been found to be responsible for considerable losses in cereals, vegetable and fruit crops.

As the soils are opaque, examination of the pathogens in situ is not possible and hence, special biological and molecular techniques have been applied for detection of their presence and quantification of their populations. Bait tests, isolation-based methods are useful to detecting and quantifying viable populations of the pathogens, but they require a long time to yield results. On the other hand, molecular methods are more sensitive and rapid in providing results. Distribution of the soilborne microbial pathogens is not uniform and variations in population may be significantly influenced by soil depth, pH, soil moisture, temperature, and organic matter composition and content. The soil is a heterogenous medium consisting of many microhabitats that vary in size, microbial activity, nutrient availability and presence of toxicants at different concentrations. Soil microorganisms mask the pathogen population due to their ability to survive saprophytically and proliferate more rapidly. In addition, following initiation of infection, the pathogen multiplies to the required level in the host plant and expression of disease symptoms occurs after completion of the required incubation period. Symptoms on the roots and the crown of infected plants can be observed directly only after destructive sampling. At the time of symptom expression, it may be nearly impossible to save infected plants, as the pathogen would have already well established itself in the internal plant tissues. However, constant and concerted research efforts taken up in different countries yielded useful results that are applicable under different agroecosystems. The pathogens may reach the soil via infected seeds/propagules, irrigation water and farm equipments. Once the pathogen reaches the soil, it is very difficult to disinfest the soils, making the field unsuitable for the cultivation of susceptible crop(s). These factors form formidable limitations and make the investigations more difficult, compared with those meant for pathogens infecting aerial plant organs.

1.3 NATURE OF SOILBORNE MICROBIAL PLANT PATHOGENS CAUSING CROP DISEASES

1.3.1 Pathogen Biology

It is essential to have a basic knowledge of soilborne microbial plant pathogens – oomycetes, fungi, bacteria and viruses. Different techniques may be employed to detect, identify, differentiate and quantify the populations of the pathogens in plants, seeds/propagules, soil and waterbodies, based on their morphological, biochemical, immunological and genetic characteristics. The usefulness of various techniques that can be applied to soilborne fungal pathogens is discussed in Chapter 2. The biological properties such as production of various kinds of spores formed during different stages of the life cycle of fungal pathogens, survival structures produced in the plant tissues or soil for overwintering during the absence of crop (primary host) plants, host range and process of infection and disease development (pathogenesis), variability in virulence and sensitivity due to chemicals and changes in the soil environment are described in Chapter 3. Various biological and molecular methods available for detection, identification and quantification of bacterial pathogens are presented in Chapter 4 for selecting suitable techniques for application in the investigations on these cellular pathogens. Bacterial pathogens show variations in the pathogenic potential (virulence) and phenomenon of pathogenesis, host range, ability to survive under different adverse environments prevailing in the soil, as discussed critically to facilitate development of disease management systems for containing bacterial diseases caused by soilborne bacterial pathogens in Chapter 5. Viral pathogens, ultramicroscopic and smallest of the soilborne microbial pathogens, are pathogenic to a variety of crop plants grown under different environmental conditions. Most of the viruses cannot exist in a free state in the soil, and they need fungal or nematode vectors for transmission from infected to healthy plants. As they cause frequently asymptomatic infections in plants, especially in asexually propagated plant materials, highly sensitive methods have to be applied for their detection, differentiation and quantification in plants, soil and irrigation water. They may have either restricted or wide host range including crop plants, weeds and wild plants that can serve as sources of inoculum for crops, when they are planted in the next season. Variations in their virulence and transmission specificity by vectors are highlighted in Chapter 6.

1.3.2 Ecological and Epidemiological Perspectives

Soil, formed from different parent materials, provides minerals and organic materials needed for plant growth and the development of all organisms, including soilborne microbial pathogens. The activities of microbial pathogens are greatly influenced by the host plant and other biotic and abiotic agents. Soil microbial communities interact with plants and also compete among themselves for the available nutrients and niches for establishment in the rhizosphere/rhizoplane. Root exudates of plants significantly influence the structure and composition of microbial community in the rhizosphere. Soils may be either conducive or ...