- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Investment - in both facilities and know-how - is essential for growth. Economists try to understand the forces that determine investment, but investment behaviour is unruly; often the term animal spirits is used to explain the resulting volatility. This volume presents studies to explain international investment behaviour and assess its impact on growth and jobs. The authors also examine policy measures to reverse the climate of low investment that has characterised recent decades.

The contributors examine how well standard models of investment work, the role of finance constraints, the effect of risk and uncertainty, the impact of alternative forms of corporate governance, the forces shaping the adoption of new technology, the impact of foreign direct investment, the effect of investment on the NAIRU and the causal structure of investment and growth. Editors introductions to the different sections of the book provide comprehensive overviews of the main theories of investment, the impact of investment on growth and employment and examine the main questions raised for policy makers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Investment, Growth and Employment by Ciaran Driver,Paul Temple in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The determinants of investment

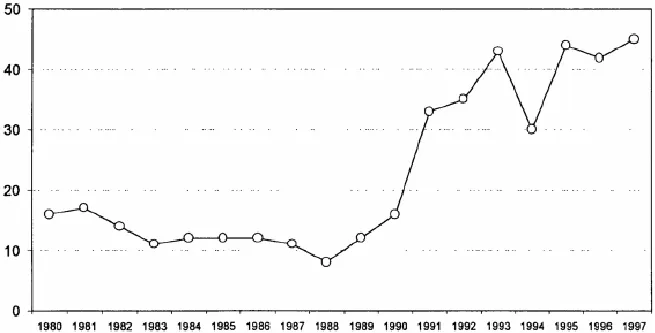

Figure 1.1 Investment articles counted.

Source: Social Science Citation Index.

Source: Social Science Citation Index.

1

Overview

A survey of recent issues in investment theory

Ciaran Driver and Paul Temple

Introduction

Interest in capital investment has risen sharply in the 1990s after stagnating at a low level during the 1980s as may be seen from the international count of relevant journal articles in Figure 1.1.1 The preceding low level of interest may have something to do with the difficulty of breaking out of the narrowly defined ‘modern’ approach to investment, originating in Abel (1980). By contrast in the 1990s we have seen a divergence in approach, which has widened the scope of enquiry not only in respect of the causes of capital investment but also its consequences. In this first overview we deal with the determinants of investment. The overview for Part II addresses the consequences, while that for Part III considers some key issues for economic policy.

Understanding investment

Despite the rise in research activity shown in Figure 1.1, there has been no breakthrough on the empirical front; the ability to forecast investment expenditures seems as elusive as ever. The average root mean squared errors one year ahead for seven forecasting models is four times larger for non-residential real fixed investment as it is for GDP growth (Granger 1994). In some ways this should not surprise given the volatility of investment expenditure which entails a stock adjustment. Nevertheless, the forecasting performance of consumer durables, which has an even higher volatility than investment is rather better. This discrepancy may perhaps be due to the long-lived nature of capital equipment and structures or to the complex interactions between firms which characterise the investment decision.

These complexities may be illustrated by listing some of the information requirements of an investment appraisal. These include:

- Construction of forecasts and sensitivities in respect of macroeconomic variables, industry demand and market share, including conjectures of rival responses, public policy, effect of investment on existing activity and availability of complementary inputs.

- Estimation of option values associated with acting (or not), including the technological and market positioning of the firm.

- Construction of a financial view including forecast cost of capital and long-run hurdle rates; conceptualisation of a market-based or managerialist philosophy on risk and liquidity constraints.

In the absence of a social context there would almost certainly be huge variation in the way in which firms assess the future. In practice, although there is variation, it tends to be tightly contained. One explanation of this is the way in which political and social influences generate a robust consensus on the external environment facing firms. These long-run expectations characterise the regime that firms face in carrying out investment decisions. When these expectations change there is unusually high uncertainty due to the possibility of a regime change. We may illustrate this idea by adapting the theory of Marglin and Bhaduri (1989) to construct the matrix of investment regimes shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Alternative investment regimes

The table illustrates a near-orthodox model of investment where the main determinants are demand and profitability with the role of demand crucial in translating current profit margins into expected profitability. Cooperative outcomes between labour and capital are possible where the likely influence of demand growth is to increase confidence in sustained profitability. In Kaleckian fashion, cooperative outcomes are unstable since they lead to a profit squeeze. The restoration of profitability tends to occur through a focus on profit-enhancing policies and accompanying destruction of demand. The resultant rise in profitability does not automatically entail cooperative growth as confidence may only be restored by a timely switch to a demand-led policy focus and a reduction in uncertainty. However, many economic variables—capital intensity, wage adjustment and expectations of inflation—adjust very slowly (Bean 1989; Wardlow 1994; Blanchard 1997). Public policy is also slow to adjust because credibility is related to policy consistency. These considerations limit the power of equilibrium analysis.

If such forces do in fact underlie the longer-term cycles in advanced economies it can readily be understood why the formal models of investment, despite their sophistication, tend to predict poorly in the medium term.2 Most theories of investment are, at bottom, simply dynamic versions of an equilibration between the expected marginal revenue product of capital and its expected marginal cost. But neither of these schedules are likely to evolve in easily predictable ways. In forming expectations about the marginal revenue product, the corporate players have to weigh up, as in the Marglin and Bhaduri model, the relative influence of current profitability and demand conditions—no easy task.

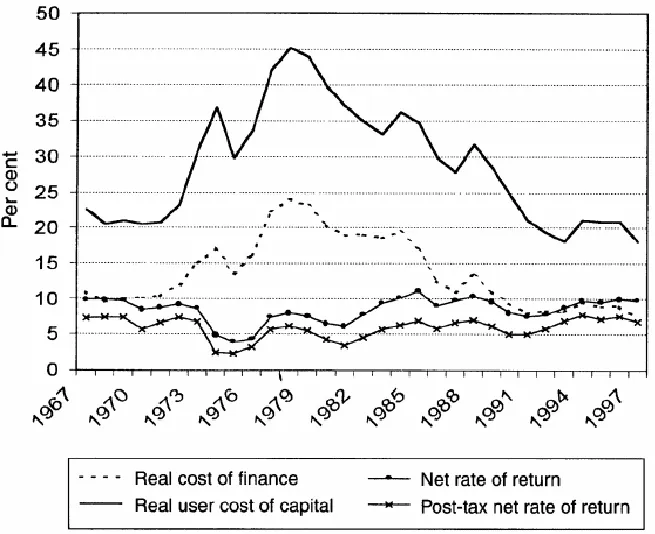

Certainly, the ex post realisations do not always bear out the simple story of equilibration between return and cost even in the medium run. In the UK, for example, as Figure 1.2 shows, the series for average profitability and average cost of investment have been diverging for over twenty years, suggesting the need for a disequilibrium analysis and the presence of constraints (Schultze 1987). At face value it might appear that the rising gap between the marginal revenue product of capital and the cost of funds should have produced an investment boom. The fact that this has most definitely not occurred needs to be explained. Possible candidates are measurement errors, the existence of constraints on investment or the occurrence of a regime shift. One important idea is that as capital flows have been liberalised, the opportunity cost of funds needs to be calculated as the rate of return on foreign assets (Young 1994; Cowling and Sugden 1996).3 If domestic investment has to meet a hurdle rate equal to this return, it could explain the coincidence of rising profitability and stagnant investment. Other explanations such as financial constraints or uncertainty are discussed in some of the chapters below.

In this overview we review some of the main aspects of modern investment theory before commenting on the individual chapters in the book. Among the most influential (and relatively recent) developments in orthodox theory have been:

- the development of dynamics and the testing of q-theories;

- the incorporation of constraints;

- models of investment under uncertainty.

In reviewing these topics we will use their simplest representative form and offer a flavour of intuition along with the formal structure of a model.

Figure 1.2 Rates of return and the cost of capital in the UK.

Source: Bank of England.

Source: Bank of England.

Dynamics

Much recent empirical work on investment follows the ‘adjustment cost’ approach which sees the investment decision as the optimal forward-looking tracking of a stochastic target. Earlier work—the flexible accelerator— stressed that there was a tradeoff between immediate adjustment to a target and the cost of rapid adjustment. The more modern version originating with Abel (1980) is in the same mould and can be simply described by a brace of equations obtained by differentiating the value of the firm (Vt) conditional on the previous period capital stock (Kt–1).

The value of the firm may be written in dynamic programming form as the current value of profits and the continuation value representing the expected value from time t+1. To save on notation we ignore depreciation and discounting and consider only the fixed factor K. Thus:

given the assumption of zero depreciation.

Differentiating Vt with respect to the ‘state variable’ Kt–1 gives the Euler equation:

The term on the left is the shadow value of one unit of capital. Repeated substitution gives the familiar condition that the shadow value of capital is the sum of the future marginal values of that capital.

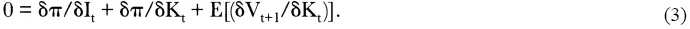

Differenting Vt with respect to the ‘control variable’ It gives:

Combining (2) and (3) gives

This states that the shadow value of capital is the marginal effect of investment (rate of change of capital) on current profits; this is the cost of investment. In a static framework that cost of investment is just the purchase price. In a dynamic framework, the right-hand side is the sum of the purchase price and an adjustment cost that is some convex function of investment, C(I).

Equations (1) to (4) offer a variety of approaches to estimating investment equations. Three basic models have been used

(a) First, equation (4) has been estimated directly by using stock market data to represent the left-hand term which is the shadow value of capital. The average valuation of the capital stock as a ratio of its replacement value (Tobin's average q) has been used to proxy the marginal value of q. If adjustment costs C(I) are assumed quadratic in the investment rate (I/K) so that marginal adjustment costs are linear, it is easy to obtain an equation from (4) which relates (I/K) log-linearly to q and to the real cost of capital.4

(b) An alternative method is to dispense with observed stock market data and to attempt to proxy marginal q by an auxiliary equation which sums future marginal values of capital. This can be obtained by forecasting future marginal revenue products using an assumed representation for the production function and an estimated vector autoregression which links successive time periods (Abel and Blanchard 1986).

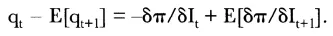

(c) A third method is to eliminate the shadow value of capital from the investment equation by using a differenced version of (4).

Using (2), the left side can be written as δπ/δKt.

Given a representation for marginal revenue product and the adjustment cost function, and using rational expectations to eliminate the expectation, this equation can be estimated without recourse to data on marginal q. However, it may pertinently be asked how account is taken of the under-utilisation of capital in this framework. With constant returns, perfect competition and stable prices for capital goods, the equation reduces to a condition relating adjustment cost now to that in the next period, i.e. investment is simply driven by the expected path of adjustment costs.

There has been some disagreement in the literature over the most promising approach. It seems generally agreed that the qtheory approach has disappointed empirically, either because of a failure of stocks to mirror fundamentals or for broader reasons of investment strategy (Blanchard et al. 1993; Chirinko 1993).5 As for the other approaches, Blundell et al. (1992) favour the Euler equation approach partly because it avoids the auxiliary assumptions that have been used to measure the shadow value of capital. It appears, however, that most estimated Euler equations do not satisfy their own theoretical restrictions and may be ‘mongrel’ relationships (Nickell and Nicolitsas 1996; see also Chirinko 1993, note 40).

A serious problem with much of the above theory is the reliance on restrictive functional forms, in particular the assumed convex quadratic form for the adjustment cost. While this makes the solution of the differential equation system tractable, deviations from it can render the solution unstable. Furthermore the a priori basis for it is thin (Rothschild 1971; Maccini 1987). Convex costs may be an element of firm behaviour, e.g. in the sense that rapid expansion induces managerial overload (Penrose 1959) or as in R&D projects where parallel rather than serial expenditures might reduce learning effects (Scherer 1986). More generally the model is explained in terms of disruption to production flow. But if these aspects of cost were binding constraints on investment at firm or business level we might expect there to be an extensive managerial discourse on the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The determinants of investment

- Part II The consequences of investment

- Part III The policy lessons