1 The vision of Taiwan new documentary1

Kuei-fen Chiu

This chapter discusses an alternative mode of filmmaking in Taiwan that was born about the time Taiwan New Cinema was coming into being: the Taiwan new documentary. There is a close connection between the rise of this new documentary practice and mass movements in the 1980s because both are concerned with “giving a voice to the voiceless.” With this theme underlining contemporary Taiwan documentaries, the filmmakers went a step further to forge rather sophisticated film languages in order to express the problem of giving a voice to the voiceless.

Three Taiwan documentaries are chosen for study to illustrate contemporary themes of “giving a voice to the voiceless.” I will discuss the ethnographic documentary Voices of Orchid Island (Lanyu guandian, 1993), the lesbian film Corner’s (Si jiaoluo, 2001), and Viva Tonal – The Dance Age (Tiaowu shidai, 2004), which resurrects historical memories of early modernity in colonial Taiwan. All three are highly acclaimed documentaries in Taiwan. I will discuss how the first two films highlight the notion of “performativity” in addressing issues of the politics of representation and interviews in documentary filmmaking. These two films exemplify Taiwan documentary filmmakers exploiting the reflexive mode to underscore the complexity of giving a voice to the voiceless. I will then analyze how the representational mode of Viva Tonal implies a new historical imaginary that substitutes the notion of cultural flows for the logic of the wounded to redefine the position of Taiwan in transnational circuits.

The Taiwan New Cinema

Usually taken to be a landmark year in Taiwan film history, 1982 was the year in which the watershed In Our Time (Guangyin de gushi) was released. Along with The Sandwich Man (an omnibus adaptation of Huang Chunming’s nativist stories, including Son’s Big Doll (Erzi de da wan’ou) by Hou Hsiao-hsien), In Our Time marked the debut of Taiwan New Cinema. These were hailed as a breakthrough in the Taiwan film industry not only because of their stylistic innovations but also because of their attempt to bring on screen “realistic images of contemporary Taiwan.”2 As described by the influential critic Zhan Hongzhi, Taiwan New Cinema revealed the young directors’ struggle for a reconnection with Taiwanese society by drawing inspiration from the realist tradition.3 Many features of Taiwan New Cinema are seen to reflect this realist penchant: the use of nonprofessionals instead of established stars, the abandonment of popular martial law-era genres for realistic portrayals of contemporary Taiwanese society, avoidance of melodramatic scenes, and, most of all, the use of dialog in Taiwanese – the language used by the majority of the people but suppressed under the Mandarin-only policy in the postwar period.4 The rise of the New Cinema may therefore be regarded as an attempt by the young generation to render their vision of Taiwan on film.

It is noteworthy, however, that Taiwan New Cinema was not “a cinema of or for the masses.”5 Critics charge that New Cinema directors eschewed contemporary controversial social issues; moreover, a large number of films by these directors were bildungsroman stories based on the directors’ or scriptwriters’ childhood memories.6 In the eyes of its harshest critics, New Cinema was the product of Western (read: American) cultural imperialism, for most of the promoters of New Cinema, including film directors and film critics exploiting the media to make New Cinema a spectacular success, drew heavily upon the film language and cultural heritages of Western film tradition in formulating Taiwan New Cinema’s achievements.7 The rise of Taiwan New Cinema was seen to be tied closely to the rise of the bourgeois class in postwar Taiwan which tried to affirm its identity through a (film) language distinguishable from the official (film) language propagated by the state apparatus.8 In this view, the box office failure of New Cinema betrays tellingly the rupture between its directors’ bourgeois esthetic outlook and Taiwanese society in general.

To some extent, critics of Taiwan New Cinema are right in pointing out the close connection between Taiwan New Cinema’s rise and the ascending power of a new bourgeois class, although the charge of New Cinema’s complicity with American cultural imperialism requires more careful handling.9There is indeed a fundamental difference between Taiwan New Cinema and xiangtu (nativist) literature of the 1970s to which Taiwan cinema has been regarded as a storied heir. While giving a voice to the voiceless was a top priority in xiangtu writers’ social and cultural vision, it was dropped in Taiwan New Cinema’s “reformation” agenda. To look for the type of film motivated by a kindred social vision that gave the impetus to xiangtu literature, we turn to a “grassroots” form of film production that was set in motion about the time Taiwan New Cinema was emerging: independent documentary film in the early 1980s.

Taiwan documentary and its social vision

With the arrest of several distinguished writers, xiangtu literature debates were brought to a sudden, premature halt. But calls for democratization continued, and waves of street demonstrations seemed unstoppable. To counter official TV news reports moderated by the government, demonstrators resorted to on-the-spot documentary filming to produce news reportage from the “people’s” perspective.10 If In Our Time set the tone for Taiwan New Cinema, the stress on eyewitnesses and grassroots vision used by a group of documentary filmmakers calling themselves “lüse xiaozu” (the Green Group) initiated new styles that would have a tremendous impact on documentary production in later decades. To boost the credibility of their eyewitness representations, the Green Group took full advantage of the indexical value of documentaries by using unsteady camera movement to underscore the “authenticity” and “reliability” of their filmic representation.11 This led to a strong emphasis on realist, “noninterfering” styles, eschewing the esthetic aspiration that marked Taiwan New Cinema. Playing a crucial role in social movements of all kinds – including the aboriginal movement, the women’s movement, and the workers’ movement that took to the streets – this new type of documentary production often took on the responsibility of giving a voice to the voiceless.12 It was self-consciously and conspicuously grassroots.

Like Taiwan New Cinema, Taiwan documentaries of the 1980s can be regarded as a landmark in Taiwan’s film history. But if New Cinema was informed by a bourgeois outlook, the new documentary was marked by its inclination to represent the marginalized and the suppressed. This was probably the first time that subordinated classes gained access to the power of mass media in Taiwan. Documentary filmmaking in Taiwan started as early as 1903 when the Japanese filmed the colony for news reportage. In 1907 a documentary of Taiwan aiming to demonstrate the efficiency and colonial achievements of the Japanese on the island was produced.13 From then on, the documentary continued to be exploited mainly as a genre of propaganda by official authorities until the early 1980s when documentary shooting was turned into a subversive tool by participants in street demonstrations. More than Taiwan New Cinema, people celebrated the documentary as something capable of disrupting the government’s tight media control.

Considered this way, it is this new type of documentary filmmaking, rather than Taiwan New Cinema, that shares xiangtu writers’ social vision. As the genre evolved in the post-martial law period (from 1987), giving a voice to the voiceless increasingly became a problem since the notion of the documentary as an objective representation of the world was questioned by new generations of filmmakers. Documentary filmmakers realized that documentaries, just like feature films, involved fiction-making.14 This is not simply because camera shooting, footage screening, and the process of editing inevitably modify and transform the raw material, but also because interviews, a prominent feature of the documentary, are highly performative.15 There is often a tension in well-made documentary films between the filmmaker’s point of view and the interviewees,’ so the subjective dimension of the discourse and methods of the documentary cannot be ignored.16 In spite of the documentary’s problematic claim to giving a voice to the voiceless, documentary filmmakers’ interest in the voice and perspective of the common people did not subside. But the representational style that dominated the 1980s declined. In place of documentaries that stressed exclusively their informational capacity, films characterized by a strong sense of reflexivity began to appear.

Reflexivity and contemporary Taiwan documentary

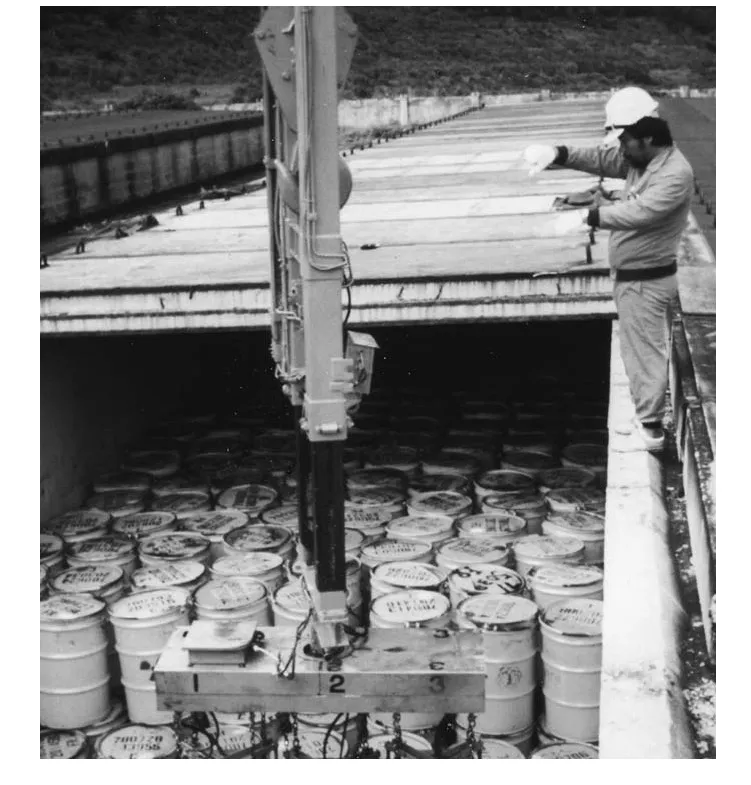

I have discussed elsewhere how the heightened sensitivity to problematic representational politics in the documentary yielded sophisticated film language in two contemporary works – namely, Voices of Orchid Island (1993) by ethnographerdirector Hu Taili and Corner’s (2001) by lesbian director Zero Chou. 17 I will venture to refine my argument here. In these two acclaimed documentaries, the filmmakers underscore the performativity of the camera to overcome the thorny problem of the camera holder “speaking for” the voiceless filmed subjects. Taking the aborigines on Orchid Island (a small island of the southeastern coast of Taiwan) as its central subject, Voices of Orchid Island is an ethnographic documentary that tackles the issue of encounters between the aborigines and the socially dominant group outside the island and the complications that ensue. The film is celebrated as a milestone in the history of visual ethnography in Taiwan, for if traditionally aborigines are subject to the ethnographic gaze, the film deliberately unsettles the ease with which the ethnographer gazes at, films, and studies aboriginal subjects. Highly conscious of the danger of “speaking for” her aboriginal subjects, Hu deliberately abandons voice-overs and interviews with on-camera experts interpreting the subjects’ lives. The conventional device of talking heads, however, is preserved. If “voice-overs” suggest the authority of the director’s voice, talking heads are often taken to convey the “true” voice of the filmed subject(s). The careful choice of conventional devices reveals the ethnographer-director’s awareness of the pitfalls of “speaking for” the aborigines. 18 However, this does not mean that the director’s voice is absent. The aborigines in front of the camera voice their anger at tourists’ exploiting gaze, but it is the juxtaposition of shots of these interviews with those of tourists’ inept behavior toward the aborigines that brings out the full force of the filmed aboriginal subjects’ protest (Fig. 1.1).

Instead of using voice-overs that suggest the unquestionable authority of the voice of the film director, Voices of Orchid Island employs a film language that implies the director’s response to what the filmed subjects say. In some of the most powerful moments in the film, reflexive comments on the inappropriateness of the director’s camera are delivered in a tour de force. For example, the film begins with shots of aboriginal interviewees protesting the gaze of outsiders. Interestingly, just as this message is being delivered to the audience through interviews of several aboriginal subjects, the camera is “roaming” around, capturing at random people and the island landscape. The ease of camera movement is disrupted when an aboriginal child suddenly turns to the camera with a loud protest: “Don’t shoot!” Throughout the film, the camera movement is accompanied by shots that explicitly or implicitly speak against its presence. If the documentary has a history of serving as a tool to bring exotic others under the scrutiny of dominant groups19 and therefore produce a combination of scopophilia (the pleasure in looking) and epistephilia (the pleasure in knowing) for viewers at the expense of subjects,20 Orchid Island asks sharp questions about the production of this viewing pleasure.

Thus, outsiders’ exploiting gaze is made an issue from the very beginning of the film. But later in the film, aborigines are shown willingly posing for photographs in exchange for money. How should we treat this exploitation of to-be-looked-at-ness by the victims themselves, which raises the question of what Rey Chow calls “the Oriental’s Orientalism”?21 The validity of the interviewees’ vigorous protest is here implicitly doubted. The ethnographer-director’s bewilderment at the contradiction between what subjects say and what they do in regard to the issue of to-be-looked-at-ness is conveyed through careful editing of the footage, which alerts the audience to the “performative” dimension of documentary interviews.22 With such deft treatment of the politics of interviews, Voices of Orchid Island, true to its title, displays voices in collision. It creates a Bakhtinian space of heteroglossia, where often two or more voices are mixed in a single utterance.23 In the process, the ethnographer’s rejection of a monologic production of meaning is fully revealed. The film ultimately is a product of collaboration between the filmmaker and her filmed subjects, who are equals in producing the complex messages of the film. The dialogic relationship between the director’s voice and filmed subjects’ voices certainly points to the full complexity of giving a voice to the voiceless.

Figure 1.1 Voices of Orchid Island: a nuclear waste dump site for Taiwan, courtesy of the director

Orchid Island is thus marked by the position of the director as an outsider to the group whose voice(s) she tries to represent in the film. In contrast, Zero Chou’s Corner’s approaches the issue of giving a voice to the voiceless from the angle of an insider of the subordinated group. Herself a lesbian, Chou faces another set of problems in producing this documentary that presents and comments on gay culture from the perspective of a gay group. While the filmmaker of Voices of Orchid Island confronts dangers of “speaking for” the voiceless, Chou deals with the difficult task of representing gay culture without subjecting her subjects to the peeping Tom pleasure of straight audiences. As in Voices of Orchid Island, the presence of the camera provokes ambiguous implications. The camera is an indispensable tool in bringing out the voice/p...