![]()

chapter one

What are Plastic Cameras?

Welcome to the exuberant world of plastic cameras! Beginning with the legendary Diana, to one of today's favorites, the Holga, these lightweight, simple-to-use, and inexpensive cameras conjure up an atmosphere of joy around image-making, create intriguing photographs, and make photographers as well as their subjects smile. Even better, the images you make can proudly take their place alongside photographs made with the most sophisticated cameras and lenses. Once you've mastered the art of photographing with a plastic camera, the possibilities of what to shoot and where to share, exhibit, or publish images are endless. Some might pick up one of the many varieties of plastic cameras for the first time and think “This can't be a real camera ”or“ How can this possibly produce good photographs?” And yet, images from these inspiring toys are being used in a wide range of commercial and noncommercial settings, from gallery exhibitions to magazines, newspapers, and advertising campaigns to fundraising for nonprofit causes. While we aficionados might still draw stares and exclamations of disbelief from digital camera users, for those of us who've been magically drawn into the world of these delightful image-making toys, there's often no going back.

Photographic technology has continually marched forward since its inception in the mid-1800s. While the advances made have been extraordinary, the basics of photography are still relevant, and even very old cameras can still function today. Like these relics, our plastic cameras totally ignore all the current camera features, but instead of this hurting their appeal, they are in fact gaining in popularity. Holga cameras, vintage Dianas, and new creations, such as the “Blackbird, Fly” and Diana +, lack meters, autofocus, auto film advance, adjustable shutters, and, of course, digital sensors. In an age when just about everyone has a digital camera and most people upgrade regularly to take advantage of the newest version's capabilities, it's astounding that anyone would choose a camera made of flimsy plastic, has a little spring for a shutter, and requires taping to keep the back from falling off. And yet, both experienced and novice photographers alike continue to adopt these toys as serious picture-making tools and as an important part of their collection of cameras.

The ways plastic cameras have managed to infiltrate the world of photography over the past 40 years have surprised even their champions. Since their discovery by American photographers in the late 1960s, they've been used by teachers at varied levels to simplify teaching the basics of photography. The ingenuity of their users has kept them from getting stuck in the realm of artist's toy though, and in the 21st century, professionals regularly use Holgas and other toys for serious photojournalism, commercial and editorial photography, portraiture, and weddings, often without even identifying their published images' humble origins.

Plastic cameras can be a surprisingly inexpensive way to get into photography. Although Holgas aren't the $ 17 they once were, they can still ring in at an affordable $ 30. Vintage Dianas are now collector's items, and newer creations tend to be priced at a premium. But with the most basic Holga 120N and some 120 film, you're ready to roll. The 120 Holgas and Dianas are a great introduction to medium-format photography, but 35 mm versions are also gaining in popularity, especially as processing options for 120 film become harder to find.

Another reason photographers love these cameras is the positive side of their flimsiness — they are lightweight. Medium-format cameras and film and digital SLRs will weigh you down far more than a 7-ounce Holga. With the proliferation of tiny digital point-n-shoot cameras, weight is less of a concern, but plastic cameras have other draws that set them apart.

Shooting with a Holga, Diana, plastic 35 mm, or even toy digital camera is a very different experience from using a “real” camera, for both photographers and their subjects. Giving a portrait subject my Holga to hold for a moment is a great way to break the ice and get them to smile, as they register with surprise that the camera weighs so little. Their experience of being photographed will always be different when the tool is a toy versus being accosted with an intimidating, complex piece of equipment. The cameras' affordability also makes them accessible for programs and classes that serve groups of youths, both in the United States and elsewhere.

Of course, the core reason for using any particular camera is the way the images will look in the end. Each camera and lens interprets the world in its own way, and the photographer needs to find the ones that complement his or her artistic vision. Negatives created with a Holga or Diana plastic lens are very distinctive; in fact, it's often possible to identify which camera made a particular image. The newer cameras and accessories are opening up even more avenues for photographers to explore their artistic vision and discover unique styles.

So -called reverse technology also has the power to bring people together, almost the opposite of the often competitive world of photography. Communities have sprung up among plastic camera aficionados, resulting in a multitude of projects, from group exhibitions, web sites, and forums to World Toy Camera Day, involving photographers from across the globe.

Since I first held a Holga in 1991, the demise of their popularity has been repeatedly predicted, but they have continued to grow in popularity to a degree that no one could have imagined. In recent years, the toy camera experience has attracted enormous numbers of people worldwide. These include both experienced photographers and novices, drawn in by the cameras' simplicity and cuteness, the perceived rebellion against more complex and expensive digital equipment, and the love of being part of a movement. The camera manufacturers have cultivated this movement and built on it. By releasing more types of cameras, colored and souped-up versions of old classics, and lots of accessories, they create choices for their widening demographic.

As long as these cameras and film are available, no one need ever be without an image-making device. In this era of more complexity, more megapixels, and more money — for some — all-manual plastic cameras provide a lifeline to pure photographic pleasure, a creative outlet for inspired artistic vision, and an antidote to the tyranny of technology.

Boarding School, 1965, © Michael Kenna. Taken with Kenna's first camera, a Diana, at age 13 while at St. Joseph's College, Upholland, Lancashire, England.

WHERE DID THEY COME FROM?

How did such unassuming toys turn into invaluable tools for serious photographers? Diana cameras first appeared in the United States in the late 1960s. They were manufactured by the Great Wall Plastics Company in Hong Kong and sold for anywhere between 69 ¢ and $ 3.00. With three apertures, one shutter speed, a difficult-to-control bulb setting, and three pictographic focus settings, the Diana barely held together and only almost kept light out. Originally stumbled upon in drugstores by curious photographers, Dianas were also discovered by educators at university photography programs, including Jerry Burchard at the San Francisco Art Institute and Arnold Gassan at Ohio University. By adopting the Diana in their beginning photography classes, they immediately leveled the equipment field for their students. Using these simple cameras, students learned the same skills in composition and creative vision that they would have learned with more expensive cameras, without the distraction of having to make complex camera adjustments. Because both the cameras and the film were cheap, students were encouraged to shoot with abandon. Dianas in hand, students and faculty alike loosened up.

This early history is discussed by those who were part of it in “$ 1 Toy Teaches Photography” by Elizabeth Truxell of Ohio University in the January 1971 issue of Popular Photography and in several issues of SHOTS Magazine during the 1990s (see Resources). Dianas appeared on the scene at a time when photography was expanding its reach, just beginning to be accepted in the academic and fine art worlds. The cameras fit in with the cultural explosion of the times, and photographers came at their imagery from a broad range of perspectives and experiences. The first work to be recognized by the fine art world was Nancy Rexroth's series Iowa, which was shown at the Corcoran Museum in 1971, excerpted in Aperture's 1974 publication The Snapshot, and published by Violet Press in 1977 as the first monograph of images made with a plastic camera.

In 1977, Popular Photography published two extensive articles devoted to the Diana camera written by Don Cyr. Included in special issues of the magazine, these must have opened up a whole new audience to the joys of the Diana. In 1979, the Friends of Photography put together The Diana Show, a juried exhibition that attracted more than 100 entrants. A catalog of the show, the first published collection of toy camera imagery, featured the essay, “Pictures through a Plastic Lens,” by David Featherstone, which became the classic treatise on the subject. Diana cameras weren't manufactured for very long; Featherstone mentions that they had already stopped being made before The Diana Show catalog was published. The Arrow, Banner, Dories, and several dozen other Diana clones continued to be made, usually in a shade of blue similar to the Diana, but in varying degrees of quality. The last of the line, the Lina, ceased to be made in the late 1980s, but for the photographer willing to troll yard sales or eBay, there are still many Dianas and her kin floating around.

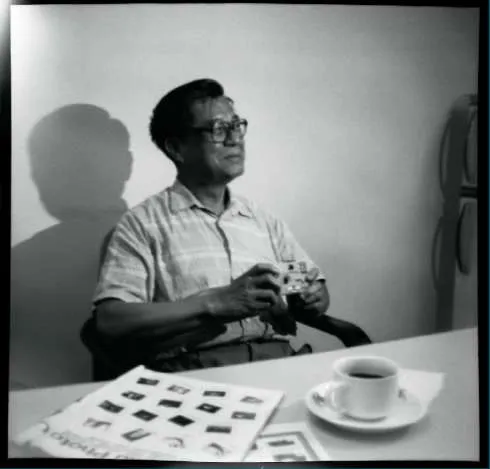

Without knowing about the legacy of the Diana, Mr. T. M. Lee ushered us into the Holga dynasty. Invented in 1982 for his Hong Kong company Tokina Corporation, part of Universal Electronics, Holgas were meant to feed the vast Chinese market for affordable medium-format cameras. The name Holga came from the Cantonese term hol-gon, meaning “very bright.” Shifted a little, for easier English pronunciation, the word resulted in Holga. Within a few years, 35 mm film took over, and the Chinese demand for the larger format fizzled. The Holga's saving grace was the United States market, where

T. M. Lee, Inventor of the Holga, © Skorj. This portrait was taken with a Fujipet camera during a visit to the Universal Electronics factory by Tony Lim and Skorj in 2005 for an interview for Lightleaks Magazine, Issue 2.

Holga soon found a new realm of popularity with American photographers. In the early 1980s, Holgas were introduced at the Maine Photographic Workshops (MPW; now Maine Media Workshops), where they took the place of Diana and Dories cameras as low-tech educational tools for the workshops' students. Holga's availability at MPW and through their store, The Resource, made them accessible to photographers at large, and word spread quickly throughout the photographic community. As their popularity grew, imports increased, surprising even their manufacturers. Sales soon topped 10,000 per year in the United States and currently about 200,000 Holgas are sold per year worldwide. Well over 1,000,000 Holgas have made their way into the hands of adoring photographers.

Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern, 1995, © Sylvia Plachy, photographed for the Village Voice. Antiquarian book dealers and companions. “We still end each other's sentences. Together we look to the future — to our next find, to our next book, to our next adventure.” Holga camera with Tri-X film and flash.

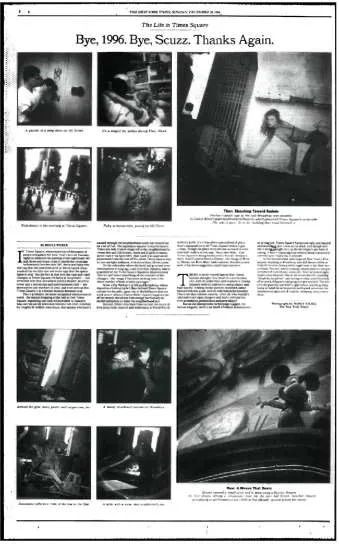

In 1986, Dan Price launched SHOTS Magazine, and introduced an entire generation of fine art photographers to Diana and Holga imagery. In the 1980s and 1990s, some established professional photographers started using plastic cameras in their work. The breakthrough into the editorial realm came with the publication of Sylvia Plachy's images in the Village Voice. In 1996, Nancy Siesel convinced editors at her employer, the New York Times, to take a chance, publishing a full-page article with 10 of her Diana camera images illustrating an article on the changing landscape of Times Square. Since then, acceptance of nontraditional images has spread into magazines, newspapers, advertising, and even videos worldwide.

21ST-CENTURY PLASTIC

These past few years are leading us into the true heyday of the Holga and plastic cameras in general. Their appeal has spread far outside beyond the

Bye 1996. Bye Scuzz. Thanks Again, © The New York Times, December 29, 1996. All rights reserved. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of the Material without express written permission is prohibited (www.nytimes.com). Ten image photo spread. Diana camera photographs by Nancy Siesel, article by Bruce Weber.

photographic community, and the demand has spurred new innovation and interest. It seems the more we are all overwhelmed by digital technology, the more popular throwbacks become, including plastic cameras, which are accepted both as serious photographic tools and as funky cultural objects. Their ever-burgeoning popularity has spawned the creation of more styles of plastic cameras, as well as other tools that create imagery reminiscent of their low-tech look, but within the digital realm.

In the early 1990s, Lomographic Society International began its bid to introduce the world to low-tech cameras with the Lomo LC-A. While neither plastic nor cheap, the simplicity and gaudy, contrasty color rendition of the LC-A endeared it to the Austrian students who stumbled upon it. They then decided that everyone should adopt their Golden Rules of Lomography, creating “Lomographers” who “shoot as many impossible pictures as possible in the most impossible of situations from the most impossible of positions.” Their main tag line is “Don't think, just shoot,” gifting photographers with a liberating manifesto. While the original LC-A is no more, now Lomographic makes the LC-A+, in addition to the Action Sampler, Super Sampler, and other multi-lens cameras. Lomographic's newest creation is the Diana+, along with its entire line of accessories. The huge success of this reinvented classic has converted many thousands of people worldwide into plastic camera enthusiasts.

To keep up the interest of those who buy their products, and to win new converts, the Lomographic Society has created a new angle on the natural congregating that tends to happen among toy users. Since 1994, the society, based in Europe, has thrown parties and events all over the world, including the LomOlymPics. LC-A, Holga, and Diana+-crazed photographers are sent out on missions o...