- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The 1992 American election saw more women running for office, at both local and national level, than ever before. The number of women elected increased by 50% in the House of Representatives and by a staggering 300% in the Senate. This book describes these key races, revealing the underlying tales of voter and institutional reactions to the women candidates and highlights the unprecedented levels of support garnered on their behalf.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Year Of The Woman by Elizabeth Adell Cook,Sue Thomas,Clyde Wilcox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why Was 1992 the "Year of the Woman"? Explaining Women's Gains in 1992

Clyde Wilcox

In many elections since the mid-1970s, journalists have written of a possible "Year of the Woman" in which record numbers of women would be elected to public office (Duerst-Lahti 1993). In 1990, when Republicans nominated a number of women to run for Senate seats, many anticipated the breakthrough election that would finally merit the label, but only incumbent Senator Nancy Kassebaum won.1 In the months leading up to the 1992 general election, journalists again began to write of a coming "Year of the Woman." A record number of women had run for and won their parties' nominations for election to the House and Senate, and polls showed that several women candidates were running competitive Senate campaigns.

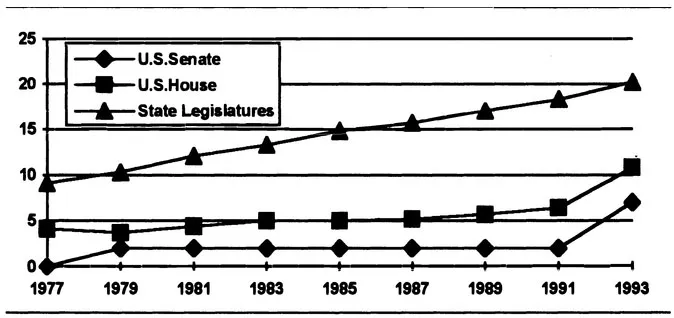

The 1992 elections proved markedly different from earlier ones. Four women won new Senate seats, and one woman incumbent easily won reelection, tripling women's representation in the upper chamber. Twenty-four new women were elected to the House, raising the number of women in that body from twenty-nine to forty-seven. Women continued to increase their numbers in state legislatures as well, to 20 percent of all seats.

After the election, the media proclaimed that 1992 had indeed been the Year of the Woman, A number of feminists and scholars objected to the label, however.2 First, to declare a "year" of women might suggest that woman had gained political parity, although the 103rd Congress would still be overwhelmingly male. That Congress remains a male bastion was evident when Carol Moseley-Braun sought a congressional identification card, and was initially issued one labeled "spouse."3 Women would need more than ten "Years of the Woman" to attain parity in the Senate, and more than seven "Years of the Woman" to reach equality in the House of Representatives. Moreover, the "year" of the woman ignores the two decades of steady progress and efforts by women who sought election to the state legislatures or to Congress, and of women who sought to elect them. The year of "the" woman suggests that the story is about successful women candidates, ignoring the role of women voters in primary and general elections, of women contributors who gave unprecedented amounts to help fund women's campaigns, of women activists who volunteered their time and skills, and of women's organizations which mobilized support for women candidates.

Commentators also noted that 1992 was not the "year of all women candidates." Some women incumbents were defeated by male challengers. Mary Rose Oakar of Ohio lost, at least in part because of the House bank scandal, and Elizabeth Patterson of South Carolina lost to a Republican backed by the Christian Coalition.4 Nearly all women who challenged House or Senate incumbents lost, often by large margins.

The 1992 election was not the "year of all woman candidates" in another sense. Almost all of the women who won new seats in the House, and all new women in the Senate, were Democrats. Most Republican women who sought to win an open seat or to unseat an incumbent in the House or Senate were defeated. Some Republicans argued that a better phrase would be the "year of the liberal, Democratic woman." The successes of Democratic women were particularly galling to those Republicans who had worked hard to nominate women in their party, especially in light of the lack of success of several highly qualified Republican Senate challengers in 1990.5

Despite these important caveats, the term "Year of the Woman" does point to one important fact: women's gains in Congress were unprecedented. Figure 1.1 shows the percentage of women who served in the Senate and in the House in each term from 1977 through 1993, and the percentage of state legislative seats held by women in each year. The 1992 election brought a sharp increase in the numbers of women in both the Senate and the House. The increase of women in the U.S. Congress from 1991 to 1993 was the largest gain during this period. The gains in state legislatures, however, were part of a steady incremental pattern of increasing numbers.

FIGURE 1.1 Percent of Women in American Legislatures, 1977-1993

Explaining Women's Gains in 1992

Why did 1992 produce the large gains in women's representation that had been expected in so many previous elections? A number of factors combined to elect more women at the national level. These factors can be divided into three types: those that relate to the behavior of candidates, those that relate to the responses of political elites, and those that relate to the behavior of voters. Record numbers of women ran for the House and Senate in 1992, in part because of the opportunities presented by an unusually large number of open seats in the House, and in part because of special circumstances that motivated women to seek election to the Senate. Political elites responded to these candidates. PACs and party committees funneled large sums of cash to women candidates, allowing them to run competitive campaigns. Finally, the 1992 election hinged on issues such as education, health care, and unemployment—issues on which women have generally been perceived as more competent than men. The issues of the campaign, combined with an electorate interested in political change, resulted in increased votes for women candidates.

Women Candidates in 1992

Research suggests that women who seek election to the U.S. Congress do not face discrimination in the funding of their campaigns, nor do they face discrimination from voters. In an analysis of women candidates for open-seat primaries in the U.S. House, Barbara Burrell reported that women candidates in these races do as well as men. She concluded that "The fact that women hold few seats in the House is primarily due to the scarcity of their numbers in these races" (Burrell 1992: p. 507).

Part of the explanation for the record number of women elected to Congress in 1992 is that record numbers of women chose to run. Burrell (1993) reported that 218 women ran in their party's primary, a substantial increase from the previous record of 134 in 1986. Fully 108 women won their party's nomination for House elections, and eleven won nomination for a Senate candidacy. Why did so many more women seek election to the U.S. House and Senate in 1992? The explanations appear to differ for the House and Senate.

Throughout the 1980s, women continued to increase their numbers in state legislatures, city councils, and county commissions. Many of these women were anxious to run for national office whenever conditions were ripe. Dolan and Ford (1993) report that women elected to state legislatures in the 1980s were more ambitious than those women elected in previous years (but see also Freeman and Lyons 1992). Women and men with this kind of electoral experience are the most likely to win a seat in Congress: throughout the 1980s, most newly elected members of the House (both men and women) have previously held elected office.6 By 1992, there existed a ready pool of ambitious, skilled women with solid political bases who were ready to seek election to Congress.

Jacobson and Kernell (1983) have argued that skilled politicians wait for the best year to mount a candidacy for the House of Representatives. A state legislator or county commissioner faces long odds in winning a House seat against an incumbent, and by mounting a challenge she frequently gives up her current office. She has a far better chance to win the seat if the incumbent has retired. If it seems likely that the incumbent will soon retire or seek higher office, many skilled politicians wait to run for the open seat. If it seems likely that the incumbent will continue to run for the House in the future, skilled politicians generally wait to run in a year in which political conditions favor their party, or until a scandal weakens the incumbent's political base.

The 1992 election provided an excellent opportunity for women (and men) in state legislatures and other state and local offices to seek election to the U.S. House. Redistricting forced many incumbents to campaign in areas they had never represented, and occasionally changed the partisan balance of the district to allow a more competitive election. Many incumbents were vulnerable because of their involvement in scandals, because they had voted for an increase in their own salaries, or because of a general electoral mood that favored change. Finally, a general anti-incumbency mood was evident in the early months of 1992, suggesting that even popular incumbents might be more vulnerable than in previous elections. Thus, strategic politicians who planned to run against an incumbent found 1992 a good year to mount their challenge. However, in 1992, most women who chose to challenge incumbents lost.

More importantly, redistricting created a number of new, open districts, and a record number of retirements brought on by redistricting, scandal, and campaign finance laws (Groseclose and Krehbiel 1993) created even more open seats. Fully fifty-two House incumbents retired in 1992, thirteen sought higher office, and two died prior to the election. Combined with newly drawn districts and incumbents who lost in party primaries, there were ninety-one open seats in the House in 1992, a far larger number than in most recent elections. For experienced women politicians who lived in these open districts, 1992 was likely to be their best shot for many years at a House seat. This was especially true for Democrats, for President Bush's popularity continued to drop during 1992, and the recession lingered. These conditions would normally lead experienced Democratic candidates to seek election to Congress, and 1992 was no exception. Redistricting allowed ambitious Democratic women and men to read these signals and declare relatively late candidacies.7

Thus, the candidacies of many of the women who sought election to the House were part of a normal pattern in politics, in which experienced politicians seek higher office in years in which national and/or local conditions maximize their chances for success. The 1992 elections provided a better opportunity than had most previous elections, and a record number of women responded to these conditions. Women's gains in the House in 1992 were due to the existence of opportunities, and of a large pool of skilled women politicians ready to exploit those opportunities.

Yet the record number of female House candidacies were also due in part to circumstances unique to the 1992 elections. As Robert Biersack and Paul Herrnson report in Chapter 9, the political parties made aggressive efforts to recruit women candidates in 1992, in part because polling data convinced party elites that these candidates would be especially attractive to voters. In addition, Roberts (1993) has reported that women's PACs made special recruitment efforts in 1992.

Because there are only thirty-three or thirty-four Senate elections in most election cycles, efforts to explain candidacy decisions frequently involve more idiosyncratic elements. Opportunities to seek election do not occur in every election in every state, and frequently prospective candidates must wait a number of years for the best opportunity to run. Most successful candidates for the U.S. Senate are those who have held important state office (e.g., governor), who have served in the U.S. House, or who have held executive office in the largest cities of the state. Like state legislators, these former state officeholders or incumbent House members generally bide their time, waiting for the best chance to challenge an incumbent or to run for an open seat.

Some of the Senate candidacies by women in 1992 fit this pattern. Dianne Feinstein had been a powerful and popular mayor in San Francisco, and she had lost a very close election for governor two years earlier. She had name recognition throughout the state, a ready list of volunteers to help her campaign, and recent experience in raising money for an expensive election. Barbara Boxer had served in the House for many years. Both women fit the normal profile of U.S. Senate candidates, and both women found 1992 a promising year to run for the Senate because of unique opportunities in their state. Feinstein took on an appointed incumbent who did not have the enthusiastic support of the conservative wing of his party, and Boxer sought election to an open seat created by the retirement of an incumbent. The 1992 election therefore posed the best opportunity to seek a Senate seat in California in several years. Had these opportunities occurred in an election a few years earlier or later, it seems likely that both women would have run.

Similarly, Geraldine Ferraro and Elizabeth Holtzman would have been strong candidates for the Senate in any year. As Craig Rimmerman notes in Chapter 6, Holtzman had narrowly lost a previous Senate bid primarily because a third candidate siphoned off some of her support, and Ferraro had been the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in 1984. Because New York has one incumbent Democratic senator, the chance to challenge the Republican incumbent Alfonse D'Amato only occurs every six years, and 1992 appeared to be a particularly good year because D'Amato had been politically damaged by scandal.

Thus, the New York and California candidacies fit a pattern of "normal politics," by which I mean that the women who sought to win Senate seats in 1992 did not appear to have been motivated by any special circumstances, but rather seized opportunities that happened to occur in 1992. As Sue Tolleson Rinehart notes in Chapter 2, however, once these women became active candidates their election campaigns were anything but "normal politics," because the media, the voters, and even the candidates interpreted their candidacies through the prism of gender. Similarly, the primary election battle between Ferraro and Holtzman was perceived differently by most observers because the two candidates were women.

Yet other women candidates for the Senate in 1992 had not served in Congress or as mayors of large cities. These women might not have been expected to run for the Senate, at least until later in their political careers. They claimed to be motivated by factors unique to the 1992 election—specifically by the Hill-Thomas hearings. The October 1991 confirmation hearings of Supreme Court nominee ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Why Was 1992 the "Year of the Woman"? Explaining Women's Gains in 1992

- 2 The California Senate Races: A Case Study in the Gendered Paradoxes of Politics

- 3 Patty Murray: The Mom in Tennis Shoes Goes to the Senate

- 4 Carol Moseley-Braun: The Insider as Insurgent

- 5 Lynn Yeakel Versus Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania: Why She Lost

- 6 When Women Run Against Women: Double Standards and Vitriol in the New York Primary

- 7 Women and the 1992 House Elections

- 8 Women in State Legislatures: One Step at a Time

- 9 Political Parties and the Year of the Woman

- 10 Women's PACs in the Year of the Woman

- 11 Political Advertising in the Year of the Woman: Did X Mark the Spot?

- 12 Voter Responses to Women Senate Candidates

- 13 Gender and Voting in the 1992 Presidential Election

- 14 Increasing the Number of Women in Office: Does It Matter?

- About the Book and Editors

- About the Contributors

- Index