![]()

1

Theorizing and researching Islamophobia/Islamophilia in the age of Trump

Critical reflexivity: The personal is political

Parker (2005a) defines reflexivity as “a way of attending to the institutional location of historical and personal aspects of the research relationship” (p.25, emphasis in original). I am writing this book as an Egyptian-Polish-American academic living in the United States (US), but who was born and grew up in Cairo, Egypt. Being a “hybrid” (Bhabha, 1994) gives me the pretext to criticize the (post)modern “world-system” (Wallerstein, 2004) ruthlessly. My “secular criticism” is informed by this Saidian principle:

even in the very midst of a battle in which one is unmistakably on one side against another, there should be criticism, because there must be critical consciousness if there are to be issues, problems, values, even lives to be fought for.

(Said, 1983, p.28, emphasis added)

Although I am from North Africa, paradoxically I am not naturally filiated, but rather culturally affiliated with Arabs (Said, 1983). Having lived in Egypt, a Muslim-majority country, for a quarter of a century means that most of my friends are Muslim. As a secular (Coptic-Catholic-Buddhist) ally of Muslims, the question of ‘Islamophobia’ has both moral and political significance to me.

I wrote my book in 2018, in the context of Black History Month, but I started working on my book in 2015 in the context of the US presidential election of 2016, which was a charged environment, to say the least. I got interested in the topic of Islamophobia accidentally through my scholarly critique of the “War on Terror” (WOT) discourse, at which point I realized that I did in fact experience Islamophobia, even though I am not Muslim.

My most memorable experience of Islamophobia took place sometime in 2011 during a film class at Governors State University, Illinois. A fellow student said the following out loud upon seeing my image in a short video I was acting in. She said, “you look like a terrorist!” (cf. Fanon, 2008, p.84), then she started laughing. I could not believe what I heard her say or the way she was saying it, so I froze. But that experience, as I thought about it over time, made me understand how certain people see me; an awareness that is still with me to this day, unfortunately.

The first assumption in the statement mentioned above is that I look like an ‘Islamic’ terrorist. The signifier ‘Islamic’ structures the logic of that statement and functions as a “quilting point” even in its absence (Parker, 2010a, p.126). The second assumption is that terrorists ‘look’ a certain way—one can guess wherefrom that person learned to make this ‘free,’ or I should say costly, association. Finally, it is worth adding, in case it is not obvious, that there was nothing regarding the film’s content or style which is related to terrorism—except ‘my look,’ of course.

Thus, is a terrorist a terrorist because of his/her look, name, or the language s/he speaks? Or is s/he a terrorist because of his/her act(s) of (post)colonial violence? Based on that experience and multiple others, I know how it feels to be a problem (Du Bois, 1903/2003, pp.3–4). I am also familiar with what it is like to be the object of “othering” (Spivak, 1985). Nevertheless, I did not understand, as a non-Muslim, why I was racialized as an object of Islamophobia. Omi and Winant (2015) define racialization as “the extension of racial meaning to a previously racially unclassified relationship, social practice, or group” (p.111, emphasis in original).

In the foreword to The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois (1903/2003) characterizes the problem of the 20th century as “the problem of the color line” (p.xli). If that is the case, what then is the problem of the 21st century? I would argue that it is the problem of the color-blind, which goes by many names: new racism, neo-racism, cultural racism, etc. I conceptualize it as (post)modern oppression, based upon Žižek’s (1997) notion of “‘postmodern’ racism” (p.33). But I ground Žižek’s ideology critique in what Collins (2000) calls “systems of oppression,” a Black feminist analytic of “intersectionality” vis-à-vis the “matrix of domination” (p.18).

(Post)modern oppression, or oppression without oppressed (Balibar and Wallerstein, 1991, p.21), in brief, is a Liberal, multiculturalist, and tolerant variation on old-fashioned scientific racism/sexism/classism, which never really went away (hence the parentheses). (Post)modern oppression is not only “individual,” but also “institutional” (Ture and Hamilton, 1992). It can also be characterized as “everyday” (Essed, 1991), since it is both Imaginary, or “interactional,” and Symbolic, or “structural” (p.2). But what about the Real dimension of (post)modern oppression? This is the dimension this book explores. In short, Muslims are not a race, yet conceptual Muslims are racialized, gendered, and classed, and thus, oppressed. Conceptual Muslims are oppressed, even if they are White. For example, people from West Asia and North Africa are considered Brown, even though they are technically “White” according to the US Census Bureau (n.d.):

A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as ‘White’ or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Arab, Moroccan, or Caucasian.

Since I am neither a Muslim nor a scholar of Islam, yet I write about Muslims vis-à-vis Islamophobia/Islamophilia, I would like to preface by saying that I am well aware that intracommunal debates regarding “Islamic Reformation” date back to at least the 18th century (Zayd, 2006). Consequently, I am in agreement with both Hasan’s (2015) defense of traditional Islam and his rejection of the “Reformation analogy.” Here is the core of his argument:

Islam isn’t Christianity. The two faiths aren’t analogous, and it is deeply ignorant, not to mention patronising, to pretend otherwise – or to try and impose a neatly linear, Eurocentric view of history on diverse Muslim-majority countries in Asia or Africa … Don’t get me wrong. Reforms are of course needed across the crisis-ridden Muslim-majority world: political, socio-economic and, yes, religious too. Muslims need to rediscover their own heritage of pluralism, tolerance and mutual respect.

(Hasan, 2015, paras.7, 11, emphasis added)

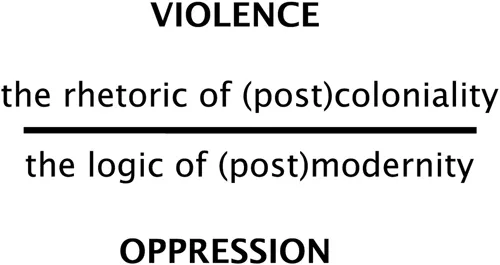

In what follows, I use psychoanalysis to critique “the other side of psychoanalysis” (Lacan, 1991/2007), that is, the ideology of (counter)terrorism-Islamophobia/Islamophilia as a “master’s discourse.” However, I enhance my Lacanian ideology critique with a decolonial reading of psychoanalysis “from the perspective and interests of the damnés” (Mignolo, 2007, p.458). Following Mignolo (2007), I engage in “critical border thinking” as part of an effort to “delink” the rhetoric of (post)colonial violence from the logic of (post)modern oppression (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Delinking the Rhetoric of (Post)colonial Violence from the Logic of (Post)modern Oppression.

Decolonial psychoanalysis

The theoretical backbone of this project is what I call decolonial psychoanalysis, wherein I radicalize Lacanian social theory by giving it a decolonial edge “from the borders” (Mignolo, 2007, p.8). Since I am not a Lacanian psychoanalyst, I am mostly engaging in what Bracher (1993) calls “a socially transformative psychoanalytic cultural criticism” (p.74). Hook’s (2008) “postcolonial psychoanalysis” is visibly a source of inspiration; other theorists informing my work include, but are not limited to, Jacques Lacan, Edward W. Said, Enrique Dussel, Walter Mignolo, Slavoj Žižek, and Ian Parker. I am also indebted to some feminist thinkers: Kimberlé Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, Sandra Harding, Deepa Kumar, Angela Davis, and Sara Ahmed. Next, I will try to describe my ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions.

A concern with “the link between language and action” (Parker, 2017, p.6), or with praxis, “theory linked directly with practice” (p.263), informs this book. I explore these links in a transdisciplinary fashion by drawing on different fields, such as: critical psychology, decoloniality, and critical terrorism studies. Lacan (1966/2006) himself was a transdisciplinarian who drew from linguistics, anthropology, and mathematics: “Must it be stated that we have to know [connaître] other bodies of knowledge [savoirs] than that of science when it comes to dealing with the epistemological drive?” (p.737, emphasis in original). With this in mind, I conceive of decolonial psychoanalysis as one theoretical resource for critical Islamophobia studies (CIS).

CIS is a radical research program that builds upon the excellent work done by the Islamophobia Research & Documentation Project, which organizes the Islamophobia Conference and publishes the Islamophobia Studies Journal. Also worth mentioning are the journal Human Architecture, which published numerous articles on Islamophobia using “the grammar of de-coloniality” (Mignolo, 2007, p.500), and the only other critical psychological research project on Islamophobia that I am aware of, that is, Marten’s (2010) Accounting for Islamophobia as a British Muslim: The centrality of the ‘extra-discursive’ in the discursive practices of Islamophobia.

CIS is politically radical (i.e., Leftist) and ontologically, epistemologically, and methodologically critical. According to Wallerstein (2004),

Radicals believe that progressive social change is not only inevitable but highly desirable, and the faster the better. They also tend to believe that social change does not come by itself but needs to be promoted by those who would benefit by it.

(pp.96–97)

If CIS had a subtitle, it would be “critical links,” (Parker, 1999) because CIS is a transdisciplinary “psychosocial praxis … the solidarity-forming consciousness of lived social contradictions” (Stevens, Duncan, and Hook, 2013, p.6, emphasis in original).

I situate CIS within the discursive turn, whose foundational theorists include: Sigmund Freud, Ferdinand de Saussure, Algirdas Julien Greimas, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, Louis Althusser, Ernesto Laclau, and Chantal Mouffe. Beginning with psychoanalysis, Freud (1900/2010), in The Interpretation of Dreams, provides us with many useful analytic tools. His “method of dream-interpretation” (p.128), for example, can be used as a method for text-interpretation. Perhaps, a text “is a (disguised) fulfilment of a (suppressed or repressed) wish” (p.183, emphasis in original). In his text-interpretation of Orientalism, Said (1978), for example, distinguishes between “manifest Orientalism” and “latent Orientalism” (p.206, emphasis in original). In other words, Said repurposes Freud’s (1900/2010) distinction between “manifest content” and “latent content” (p.295, emphasis in original) for a critique of coloniality/modernity. In the interpretation of one of his dreams, Freud (1900/2010) concludes that certain “elements” or signifiers:

[C]onstituted ‘nodal points’ upon which a great number of the dream-thoughts converged, and because they had several meanings in connection with the interpretation of the dream. The explanation of this fundamental fact can also be put in another way: each of the elements of the dream’s content turns out to have been ‘overdetermined’—to have been represented in the dream-thoughts many times over.

(p.301)

The Freudian notion of “nodal points” would appear in Lacan (1966/2006, p.419) as points de capiton, often translated as button ties or quilting points, and would also appear in Laclau and Mouffe (1985/2014, p.99). The concept of “overdetermination” would also be picked up by a number of researchers (e.g., Hook, 2013; Lapping, 2011; Malone and Roberts, 2010).

Moving on to structural linguistics, de Saussure (1916/1959) defined the “linguistic sign” as “the combination of a concept [signified] and a sound-image [signifier]” (p.231). Lacan (1966/2006) took up this formulation but emphasized the primacy of the signifier over the signified. Here is the central teaching of de Saussure (1916/1959): “The bond between the sig...