eBook - ePub

School Climate

Measuring, Improving and Sustaining Healthy Learning Environments

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Like a strong foundation in a house, the climate of a school is the foundation that supports the structures of teaching and learning. This book provides a framework for educators to look at school and classroom climates using both informal and formal measures. Each chapter focuses on a different aspect of climate and details techniques which may be used by heads or classroom teachers to judge the health of their learning environment. The book sets out to enhance understanding of the components of a healthy learning environment and the tools needed to improve that environment. It also looks at ways to assess the impact of change activities in improving and sustaining educational excellence. The international team of contributors bring perspectives from the school systems in America, UK, Australia and Holland.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access School Climate by H. Jerome Freiberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Measuring, Improving and Sustaining Healthy Learning Environments

H.Jerome Freiberg and T.A.Stein

Why is Climate so Important to Learning?

School climate is the heart and soul of a school. It is about that essence of a school that leads a child, a teacher, an administrator, a staff member to love the school and to look forward to being there each school day. School Climate is about that quality of a school that helps each individual feel personal worth, dignity and importance, while simultaneously helping create a sense of belonging to something beyond ourselves. The climate of a school can foster resilience or become a risk factor in the lives of people who work and learn in a place called school.

A school’s climate can define the quality of a school that creates healthy learning places; nurtures children’s and parents’ dreams and aspirations; stimulates teachers’ creativity and enthusiasm, and elevates all of its members. It is about the special quality of a school that the voices of the children and youth (described in Freedom to Learn, Rogers and Freiberg, 1994) speak to when they explain why they love their schools:

“All my teachers show respect to all of the students in the classes, and so we show respect to them”.

“They treat you like family”.

“If I was you, I would come to this school because, well, it’s like family”.

“This is just really our home….”

“On a personal basis, they [the teachers] go to each individual and ask how you are doing…. It’s hard. You can tell by their faces at the end of the day…. Like they’re real tired, but they are still willing to help you out”.

“You have to start with the students. If you can somehow make them feel like they have a place in the world, then they would want to learn more about how to live in that world”.

“I think our freedom is more freedom of expression than just being wild and having no self-control. It’s like we have a purpose, and so our freedom is freedom to express ourselves”.

“Most of the teachers here really care about me. They help not just with the subjects they teach, but with other subjects and personal things. It is different than other schools where they tell you to get your mind off anything that is not their subject”.

“Most of the teachers want us to study and do well in school so that we can do well in life. If I dropped out of school, my teachers would be disappointed”.

“The teachers care about your grades; they care about the whole class. They help you out a lot…. You can go up to them, they listen to you, they support you. They do things out of the ordinary that teachers don’t have to do…. They just don’t teach you math, they find out how you are doing. If they have an off period, you’re welcome to come talk with them. Even, I mean, problems with your school-work or just problems like at home, they try to help”.

“She’ll give you a chance. When you do something wrong, she’ll let you do it over again until you get it right… [In] other schools you don’t get a chance, they would be yelling at you. They just tell you that you are suspended. They won’t even talk to you. You know, Ms. Jones, she’ll never let you give up”.

“When you are at regular school, you do something wrong, they’d either say, ‘You got detention,’ or ‘You have suspension,’ but at this school, they try to help you out with your problems. This is a school of opportunity”. (pp. 3– 16)

It is also about a seventh grade class, in an inner-city middle school, who feel the responsibility for their learning that they don’t need a teacher to supervise their actions. This is put to the test when their teacher is absent and the substitute did not show. A student journal reflects that day:

“I feel lucky today because the day has just started and we have already been trusted in something we have never been trusted on, being alone. It is 8:15 and everything is cool. Nothing is even wrong….”

When students become citizens of the school, they take responsibility for their actions and those of others. On the October day that Sergio wrote about, a student sent the attendance to the office, while another student reviewed the homework with the class and started classroom presentations scheduled for the day. When the substitute teacher finally arrived, the students were engaged in learning. They had been taking responsibility for the classroom operations since September and, in a sense, were being prepared for this experience. What occurred in the school or classroom before the event to create a climate that said it was all right to take the initiative to learn without an adult being present? What factors support the students’ decision to embrace a norm that encourages order rather than chaos, quality of work rather than the prevailing norm for doing the minimum? A program entitled Consistency Management and Cooperative Discipline (CMCD) (see Freiberg, Stein and Huang, 1995; Freiberg, 1996, 1999 for additional explanation of the program) had been in place for two years at the middle school. The CMCD program supported students being citizens of the learning environment rather than tourists— taking responsibility for their actions and the actions of others. The program changed the existing climate that was controlling and untrusting to one that was supportive and gave students opportunities for experiencing the skills necessary for self-discipline.

Climate as Metaphor

If I say “School climate, what is the first word that comes to your mind?” the usual word association from educators is “feel”, “well-being”, “health”, “learning environment”, “safety”, (both physical and psychological) “openness”, and “caring” within schools and classrooms. On the Internet searching the term “school climate” brings over five million matches. Narrowing those down with greater detail in the search will provide more than 145 sites that relate directly to the topics presented in this book. The number of sites has tripled in the last few years. When defining the climate of a school we tend to use metaphors similar to the descriptions listed above. A school is not an organic being in the biological sense but it does have the qualities of a living organism in the organizational and cultural sense. The physical structure of schools can have direct influences on the health of individuals who work and learn there. The amount of light, noise, chemicals, and air quality are part of most work environments—schools are no different. Beyond the physical nature of schools there are other elements that reflect the way people interact and this interaction produces a social fabric that permeates the working and learning condition.

Climate: Organizational or Cultural?

School Climate: Measuring, Improving and Sustaining Healthy Learning Environments, takes both an organizational climate and cultural view of schools with the former more predominant in the book. Hoy, Tarter and Kottkamp (1991) distinguish between climate and culture in how schools are viewed, with school or organizational climate being viewed from a psychological perspective and school culture viewed from an anthropological perspective. School Climate derives its knowledge from both fields of inquiry. Some authors within the book provide perspective and climate measures that can quantify elements of school organization through validated survey instruments, while other authors examine the school culture and use stories, discussions, cases, student drawings, teacher and student journals, interviews, video and ambient noise check lists to describe what is occurring in schools and classrooms.

This book provides more than one pathway to help those most directly involved in schools to determine the health of the learning environment. If one believes in continuous improvement, then a healthy climate for learning is best determined by those in the environment who can draw from multiple sources of data and feedback, using measures or approaches that reflect the values and norms of the near and far school community and respond to pressing issues and questions.

National School Climate Report Cards

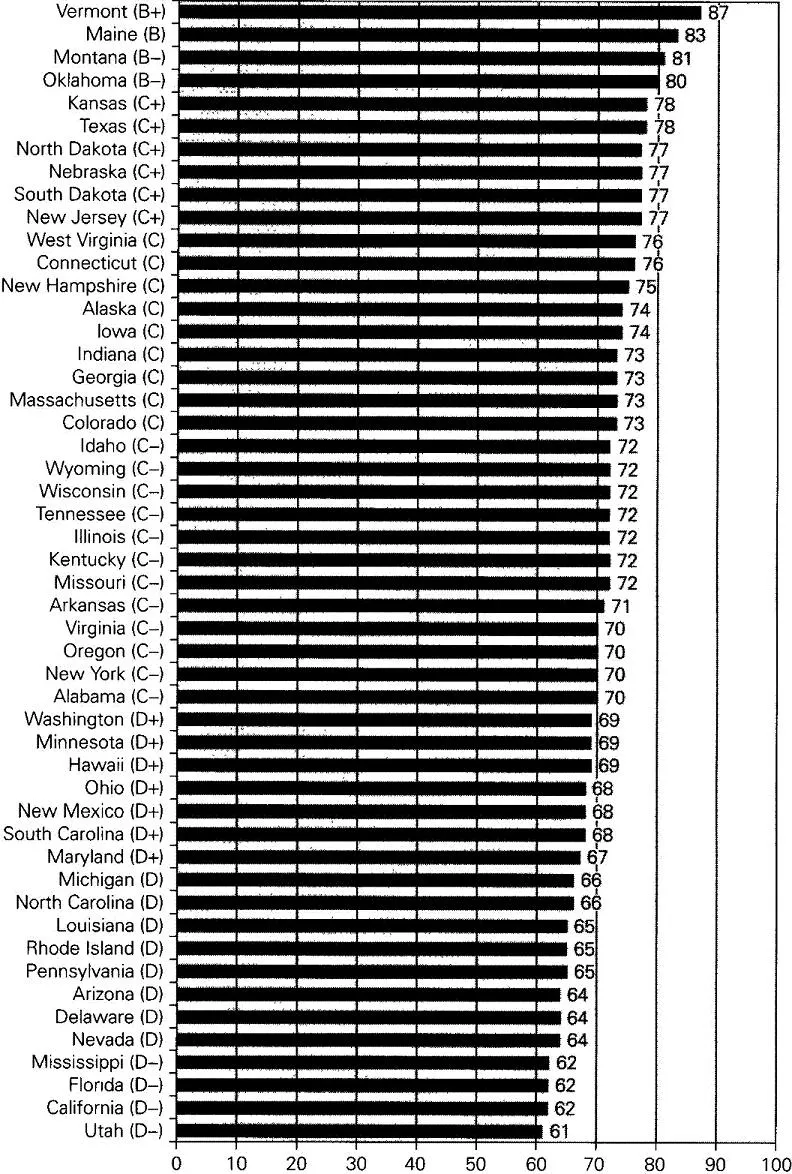

The issue of school climate has been catapulted to national educational prominence. As the world moves into the information age, then knowledge more than manufacturing becomes the driving force behind educational policies. The chairman of the State Board of Education in Texas described how a two fold increase in oil prices would bring an additional 26 billion dollars into the state. However, if every high school graduate in the state added four years more of education, they would also bring 26 billion dollars into the state. The learning environment of students emerges as a much more significant economic as well as social and educational issue for the new millennium. Moving beyond high school to higher education requires a different learning environment and needs to start very early in a child’s schooling experience. Figure 1.1 shows the ratings and rankings by Education Week (1997) of the schools in each state in the United States. They used class size, ratio of pupils to teachers in secondary schools, school organization and school safety as criteria for giving a grade from A to F on how positive the climate was. Of the larger states, Texas with a score of 78 was ranked in the top six of all states, with California being ranked near the bottom with a score of 62. The state with schools with the best climate was Vermont (87) and the worst was Utah (61). Teacher Magazine (1998) reported another climate “report card” using class size and student engagement (student absenteeism, tardiness, and classroom misbehavior) criteria. Maine scored at the top of this list with a score of 81, Vermont was fifth with a score of 77. Texas was given a score of 75 and California a “failing” grade of 51. No state received a score of 90 or better in either report card.

State Policy and School Climate

Many of the factors identified by the two report cards (class size and teacher/ student ratios) are beyond the control of many local schools as they are determined by state policy based on per pupil funding. Policy and funding issues at the state level can influence the climate of schools at the local level. Texas in the late 1980s, for example, began to “roll-out” reductions in class size to 22:1, beginning at the kindergarten and first grade levels (5–6 year olds) and expanded this reduction in class size each year until grade four (10–11 year olds). After a decade of smaller classes, changes in class size which occurred over several years, allowed for the orderly hiring of teachers and building of additional classrooms. In 1998, California which has suffered under nominal support for schools owing to taxing limitations, mandated a reduction in class size in one year. It will take several years to make the transition in construction and hiring from large classes (35–40 students) to smaller, 22 students per class. The change in California also comes at a time when demographics of an ageing teaching profession are resulting in higher levels of retirements, resulting in shortages of teachers. This problem will only grow, as it is estimated by the US Department of Education that nearly two million new teachers will be needed in the United States during the next fifteen years. This problem is not unique to the United States. The ageing teaching population throughout Europe and Japan will result in a transformation of the teaching profession. The climate of a school may be affected by many factors.

Source: ‘Quality counts’: A supplement to Education Week. Jan. 22, 1997 Vol. XVI

Figure 1.1 State by state: School climate grades

Given the trend in the United States and other nations to quantify everything, one has to be somewhat cautious that these “report cards” do not become another source of stress for school-based educators. However, with some persistence and care, these state-by-state comparison reports cards could become a positive source for improving some climate factors in states that need significant reductions in school and classroom size and teacher to student ratios. There is a tendency for those in education and the larger community, to seek one solution, one definition and one approach to a problem. School climate is a multifaceted endeavor and how one sees a problem also shapes its definition.

Research on School Climate

During the last twenty years there has been extensive research on identifying the factors that comprise the quality of a school (see Brookover, Beady, Flood, Schweitzer and Weisenbaker, 1979; Rutter, Maughan, Mortimore, Ouston and Smith, 1979; Lightfoot, 1983; Hoy, Tarter and Kottkamp, 1991; Teddlie and Stringfield, 1993; Rogers and Freiberg, 1994; Fashola and Slavin, 1998). The research has been guided by many different voices. These range from talking about schools as if they were akin to factories, identifying the characteristics of the inputs necessary to obtain the desired outputs, to talking about schools as if they were akin to families, stressing the dynamics of caring which ground the kind of positive familial relationships which lead to healthy growth.

If stories and student and teacher perceptions form the spirit of climate, then research methodology known as meta-analysis, in which findings...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Measuring, Improving and Sustaining Healthy Learning Environments

- Chapter 2: The Role of School and Classroom Climate In Elementary School Learning Environments

- Chapter 3: Using Informal and Formal Measures to Create Classroom Profiles

- Chapter 4: Using Learning Environment Assessments to Improve Classroom and School Climates

- Chapter 5: Organizational Health Profiles for High Schools

- Chapter 6: Organizational Climate and Teacher Professionalism: Identifying Teacher Work Environment Dimensions

- Chapter 7: Perceptions of Parents and Community Members As a Measure of School Climate

- Chapter 8: The Teachers’ Lounge and Its Role In Improving Learning Environments In Schools

- Chapter 9: The Impact of Principal Change Facilitator Style On School and Classroom Culture

- Chapter 10: The Phoenix Rises from Its Ashes Doesn’t It?

- Chapter 11: Three Creative Ways to Measure School Climate and Next Steps

- Notes On Contributors