- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

About this book

This compact yet complete guide to the diagnosis and treatment of endocrine and metabolic disorders combines the advantages of a short text book with those of an atlas, and provides thorough discussion of each disease supported by a wealth of images. Each topic is covered by a specialist contributor. While reflecting the great advances in biochemic

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism by Pauline Camacho in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Endocrinology & Metabolism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Thyroid disorders

Jason L. Gaglia

Jeffrey R. Garber

Normal thyroid

Thyrotoxicosis

Graves’ disease

Hypothyroidism

Thyroiditis

Louis G. Portugal

Alexander J. Langerman

Thyroid cancer

Normal thyroid

ANATOMY

During development, the thyroid gland originates as an outpouching of the floor of the pharynx. It grows downward, anterior to the trachea, with the course of its downward migration marked by the thyroglossal duct. The thyroid sits like a saddle over the trachea with the two lateral lobes of the thyroid connected by a thin isthmus, which sits just below the cricoid cartilage. Normally, each lobe is pear shaped, 2.5–4 cm in length, 1.5–2 cm in width, and 1–1.5 cm in thickness; the gland typically weighs 10–20 g in an adult depending upon body size and iodine supply. A pyramidal lobe may extend upward from the isthmus on the surface of the thyroid cartilage and is a remnant of the thyroglossal duct.

The thyroid gland has a rich blood supply with the two superior thyroid arteries arising from the common or external carotid arteries, the two inferior thyroid arteries from the thyrocervical trunk of the subclavian arteries, and a small thyroid ima artery from the brachiocephalic artery at the aortic arch. The venous drainage is via multiple surface veins that coalesce into superior, lateral, and inferior thyroid veins. Blood flow is about 5 mL/g/min but in hyperthyroidism this may increase 100-fold. Other important anatomic considerations include the relative proximity to the parathyroid glands and the recurrent laryngeal nerves.

HISTOLOGY

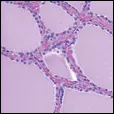

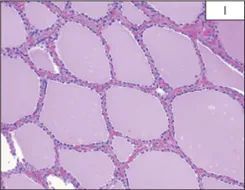

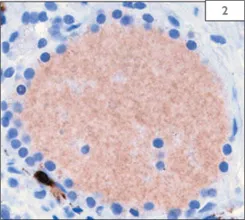

The thyroid gland consists of a collection of follicles of varying sizes. These follicles contain a proteinacous material called colloid and are surrounded by a single layer of thyroid epithelium (1). These follicle cells synthesize thyroglobulin which is extruded into the lumen of the follicle. The biosynthesis of thyroid hormones occurs at the cell–colloid interface. Here thyroglobulin is hydrolyzed to release thyroid hormones. In addition to the follicular cells are other light appearing cells, often found in clusters between the follicles, called C-cells (2). These cells are derived from neural crest via the ultimobranchial body and secrete calcitonin. In adults, the C-cells represent about 1% of the cell population of the thyroid.

THYROID HORMONE

Thyroid hormone synthesis requires iodide, the glycoprotein thyroglobulin, and the enzyme thyroid microsomal peroxidase (TPO). Synthesis involves several steps including: (1) active transport of I– into the cell via the Na/I symporter; (2) iodide trapping with oxidation of iodide and iodination of tyrosyl residues in thyroglobulin catalyzed by TPO, forming moniodotyrosine (MIT) and diiodotyrosine (DIT); (3) coupling of iodotyrosine molecules to form triiodothyronine (T3) from one MIT and one DIT molecule and thyroxine (T4) from two DIT molecules; (4) proteolysis of thyroglobulin; (5) deiodination of iodotyrosines with conservation of liberated iodide; and (6) intrathyroidal 5’-deiodination of T4 to T3, particularly in situations of iodide deficiency or hormone overproduction.

Thyroid hormones are transported in the serum bound to carrier proteins. It is the much smaller free fraction that is responsible for hormonal activity (typically 0.03% for T4 and 0.3% for T3). The three major thyroid hormone transport proteins are thyroxine-binding globulin, albumin, and transthyretin (thyroxine-binding prealbumin), which carry 70%, 15%, and 10% respectively. A number of conditions and medications can affect carrier protein concentration or binding (Table 1). Peripheral deiodinases convert T4 to the more active T3 or inactive reverse T3.

The production of thyroid hormone is normally controlled by the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) produced in the hypothalamus reaches the thyrotrophs in the anterior pituitary via the hypothalamic–hypophysial portal system and stimulates the synthesis and release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH acts upon the thyroid to increase thyroid hormone production. Negative feedback, primarily via T3 (which may be locally generated from T4 via type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase), inhibits TRH and TSH secretion.

1 Normal thyroid. The thyroid gland consists of a collection of follicles where thyroid hormones are produced and stored. Each follicle consists of central colloid surrounded by one layer of follicular cells. (Courtesy of Dr. James Connolly.)

2 C-cell is demonstrated in the classic parafollicular location with calcitonin staining in brown. (Courtesy of Dr. James Connolly.)

Table 1 Factors influencing total thyroid hormones levels |

Increased binding globulin • Congenital • Hyperestrogen states (pregnancy, ERT, SERMs, OCPs) • Illness: acute hepatitis, hypothyroidism (minor) |

Decreased binding globulin • Congenital • Drugs: androgens, glucocorticoids • Illness: protein malnutrition, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, hyperthyroidism (minor) |

Drugs affecting binding • Phenytoin • Salicylates • Mitotane • Heparin (via increased free fatty acids) |

ERT: estrogen replacement therapy; OCP: oral contraceptive pill; |

SERM: selective estrogen receptor modulator. |

Thyrotoxicosis

DEFINITION

Thyrotoxicosis occurs when increased levels of thyroid hormone lead to biochemical excess of the hormone at the tissue level. Increased levels of thyroid hormone leading to thyrotoxicosis may result from the overproduction of thyroid hormone (termed ‘hyperthyroidism’), leakage of stored hormone from the gland, or exogenous thyroid hormone administration.

ETIOLOGY

Many cases of thyrotoxicosis are from autoimmune antibody-mediated stimulation (Graves’ disease), gland destruction (thyroiditis), or autonomous nodular disease. Other less frequent causes of thyrotoxicosis include stimulation of the TSH receptor by high human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels, TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas, pituitary-specific thyroid hormone resistance, struma ovarii, functional metastatic thyroid carcinoma, thyrotoxicosis factitia, neonatal Graves’ disease, and congenital hyperthyroidism.

Iodine containing drugs such as iodinated contrast agents or iodine rich foods such as kelp may precipitate thyrotoxicosis in susceptible individuals, especially in iodine deficient areas, and is termed Jod–Basedow disease. Amiodarone may precipitate thyrotoxicosis via iodine excess (type 1) or a drug-induced destructive thyroiditis (type 2).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Common symptoms of thyrotoxicosis include palpitations, nervousness, shakiness, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, irritability, emotional lability, increased appetite, heat intolerance, fatigue, weakness, exertional dyspnea, hyperdefecation, decreased menses, and brittle hair. Although weight loss is more typical, approximately 10% of affected individuals gain weight likely due to a mismatch between increased metabolic demand and polyphagia. Due to changes in adrenergic tone, older individuals with thyrotoxicosis may lack many of the overt symptoms seen in younger individuals and instead present with what has been termed ‘apathetic thyrotoxicosis’. Often weight loss, fatigue, and irritability are the major complaints in this age group. They may be depressed and have constipation rather than frequent stools. Atrial fibrillation, crescendo angina, and congestive heart failure are also not uncommon in this population.

Signs of thyrotoxicosis include tremors, warm moist skin, tachycardia, flow murmurs, hyperreflexia with rapid relaxation phase, and eye signs. Lid retraction or ‘thyroid stare’ may be seen with any cause of thyrotoxicosis and is attributed to increased adrenergic tone. True ophthalmopathy is unique to Graves’ disease and may include proptosis, conjunctival injection, and periorbital edema. Patients with Graves’ disease also typically have a goiter and may have a thyroid bruit from increased intrathyroidal blood flow, while patients with autonomous adenoma(s) frequently have palpable nodule(s).

DIAGNOSIS/INVESTIGATIONS

Measurement of serum TSH followed by free T4 or T4 index are the initial laboratory studies when thyrotoxicosis is suspected. If free T4 (or T4 index) is normal and TSH is undetectable, a T3 level should be checked to evaluate for T3 thyrotoxicosis. Other laboratory findings that may be associated with thyrotoxicosis include mild leukopenia, normocytic anemia, trans-aminitis, elevated alkaline phosphatase (particularly from bone, but liver alkaline phosphatase may also be elevated), mild hypercalcemia, low albumin, and low cholesterol. A number of medications including dopamine and corti-costeroids may decrease TSH but should not be confused with thyrotoxicosis as the free T4 and/or T3 are not elevated.

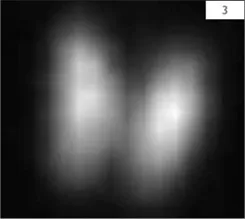

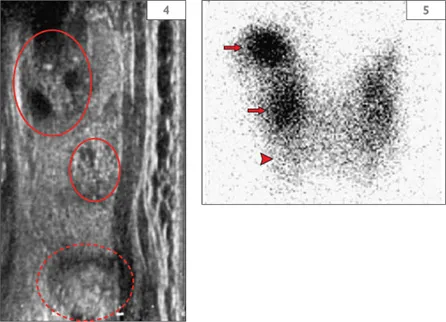

Once biochemical thyrotoxicosis is confirmed, the underlying etiology is usually determined by clinical findings or functional and/or structural assessment of the gland. Quantitative assessment of functional status may be obtained with radioactive iodine uptake. An inappropriately high uptake (uptake should normally be suppressed in the setting of a suppressed TSH) confirms hyperthyroidism while a low uptake may be seen with the thyrotoxic phase of thyroiditis, exogenous thyroid hormone ingestion, or thyroid hormone production from an area outside of the neck. A scan with I123 or 99mTc pertechnetate can be used to obtain further functional information with images depicting the distribution of trapping within the thyroid gland. Uniform distribution in a hyperthyroid patient most often suggests Graves’ disease (3). Activity corresponding to a nodule with suppression of the rest of the thyroid suggests a toxic adenoma. A patchy distribution may be seen in toxic multinodular goiter. Structural information may be obtained with physical examination and thyroid ultrasound (4,5). This should be correlated with functional data to ensure that another concurrent process such as thyroid cancer is not overlooked.

3 I123 scan showing increased and homogenous uptake of radioiodine in Graves’ disease.

4, 5 Right sagittal thyroid ultrasound (4) and I123 scan (5) correlation. The superior and middle nodules (circled) on ultrasound correlate with the areas of increased uptake on the scan (arrows) while the inferior nodule (dotted circle) corresponds to a relatively photopenic area and warrants further evaluation (arrowhead). (Courtesy of Dr. Susan Mandel.)

Although the cause of thyrotoxicosis can usually be determined by history, physical examination, and radionuclide studies, in unclear situations the measurement of circulating thyroid autoantibodies may be helpful. A low thyroglobulin level may be useful in differentiating thyrotoxicosis factitia from other etiologies.

MANAGEMENT/TREATMENT

Complications of untreated hyperthyroidism may include atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, and osteoporosis. Regardless of etiology of the thyrotoxicosis, beta-blockers, most commonly propranolol, may be used for heart rate control and symptomatic relief. Rate control is particularly important in individuals who have developed an arrhythmia or a rate-related cardiomyopathy. Once a euthyroid state is achieved, the bet...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- A Color Handbook of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- CHAPTER 1 Thyroid disorders

- CHAPTER 2 Diabetes mellitus

- CHAPTER 3 Metabolic bone disorders

- CHAPTER 4 Hypothalamic–pituitary disorders

- CHAPTER 5 Adrenal disorders

- CHAPTER 6 Female and male reproductive disorders

- CHAPTER 7 Lipid disorders

- CHAPTER 8 Multiple endocrine neoplasia, neuroendocrine tumors, and other endocrine disorders

- Further reading and bibliography

- Index