![]()

Chapter 1

Learning, Motivation and Performance

Introduction

The study of learning and motivation is important because it seems to be fairly certain that the majority of sportsmen in general and tennis players in particular, fail to fulfil their potential ability. The barrier to progress seems to be a psychological one—a classical example being the attempts to break the 4 minute mile in the early 1950s. This psychological barrier is largely determined by a player's own expectations of the standards he will reach. A number of principles and strategies are advanced for motivating young sports people to continue to develop their skill. The importance of an individual approach is emphasized because of the varying needs of particular players who really need to be treated often in quite different ways. Thus, if a coach is to help motivate a player he must really come to know him as a person.

In this chapter the relationship between success and failure and motivation is examined together with how this influences levels of aspiration or of expectancy of future success. The effect of praise and criticism on the motivation of players is also discussed.

The coach's expectation of a player's potential can be a very powerful factor influencing the motivation to continue to practise. With respect to his match and tournament performance an individual will very often fulfil the expectations of his coach, tending to do well if these are high and optimistic and tending to do badly if these expectations are low and pessimistic. There is, in fact, much research ouside sport, particularly in the education field, concerning the powerful influence which the expectations of ‘significant others’ has on an individual's own motivation and expectations. By ‘significant others’ is meant the people who are regarded by the player as being important. In tennis this is likely to be the coaches and the selectors of the representative teams and training squads.

Considerable attention is given to the relationship between the intensity of motivation or level of arousal and performance in the competitive match situation. Generally people play best at moderate levels of arousal and there is, in fact, an optimum level of arousal for maximum performance for each player. It is at the two extremes of high and low levels of arousal that individuals do least well.

Individual differences in levels of intensity between people before competitive events mean that to perform at their best some players will need to be ‘psyched up’ and others to be ‘psyched down’ to use the American expressions. Care must be taken to see that young competitors do not become over-aroused, excited and agitated resulting inevitably in a deterioration in their performance. As is the practice with the managers of some professional football clubs, for example, exhorting highly aroused players to show still greater effort is counterproductive, bringing some of them to a state of near hysteria. They are effectively ‘psyched out’ before the game even starts. This is evidenced by the number of goals which are missed when it should have been much easier to have scored.

Ways in which motivation can be enhanced are discussed and the final section of this chapter is concerned with a very serious discussion of the intensity of arousal and performance and the implications for the coach who has a crucial role to play.

Reaching international level in any major sport involves a long, arduous course of practice and training extending over many years. Progress rarely takes a uniform path and the way to the top is characterized by ups and downs in performance interspersed by periods when no improvement or apparent improvement is taking place.

Learning

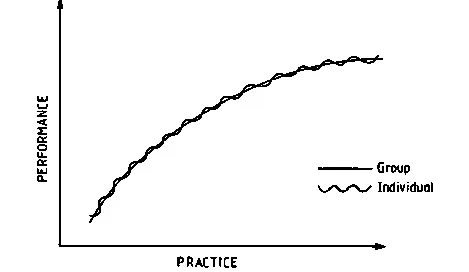

Progress towards becoming efficient in any athletic activity can be represented graphically by a learning curve. In plotting such a curve or progress chart the horizontal axis measures the number of successive trials or practice sessions and it is usual for the vertical axis to measure performance although sometimes it will measure time or the number of errors. If performance is measured the curve rises with increasing practice; if time or the number of errors is measured the curve falls. A learning curve reveals the rate of improvement and also changes in this rate. As we would expect most curves show variations in the rate of improvement. Curves measuring learning for most sports (Figure 1) are generally negatively accelerating, that is to say they show the fastest rate of gain in the early stages of practice and the slowest rate as an individual approaches the limits of his ability. Such a curve tends to occur when the activity is relatively easy and when people become bored with the sport and begin to lose interest. Sooner or later all learning curves will show a slowing down in the rate of improvement. This is because part of the practice sessions will be spent in merely maintaining the gains already achieved. As learning advances this tends to be true to a progressively greater extent with players

FIGURE 1: Idealized learning curve

having to spend progressively more and more time in practice merely to maintain the level of efficiency already achieved. Then too, as a player begins to approach the limits of his ability it takes more effort and more time to improve still further. Other factors, such as fatigue, a sense of sufficiency, the lack of desire for further advancement and inappropriate practice in the form of the needless repetition of basic skills and routines which have already been thoroughly mastered and which players see as being quite pointless.

The message of this for the aspiring sportsperson is that he cannot expect the same improvement as previously from the same amount of practice. It is important for people to know that this is almost inevitable and that younger competitors will be seen to be ‘catching up’ as they need less practice to improve at their lower level of skill.

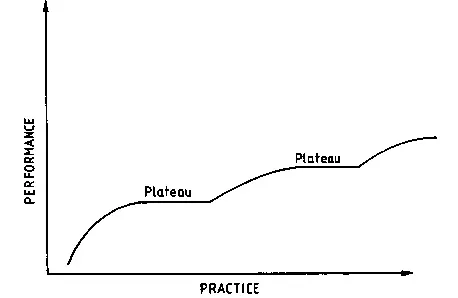

Plateaux are a common feature of most learning curves. These are graphically represented by a horizontal stretch in the curve indicating a phase when little or no measured change takes place (Figure 2). Plateaux can appear at various stages in the learning process and generally indicate only a temporary halt to improvement. A plateau in a learning curve does not necessarily mean that learning is not taking place. It may be that various aspects of a player's game, skill or technique are undergoing improvement which are not reflected in overall performance. Once these have been integrated and consolidated the learning curve will rise again. In

FIGURE 2: Idealized learning curve with plateaux

more simple terms latent or ‘hidden’ learning could be taking place over the span of the ‘plateau’ as it is indicated by performance scores.

Plateaux can be discouraging for players trying to improve upon their performance, and from the motivational point of view they are best avoided. The coach can be of considerable help at this stage by giving encouragement and support. He/she should point out that everybody is beset with such periods in their development when it seems that the standard of play has become more or less static.

Composite scores for a group of players as they are represented on a graph can provide the coach with valuable information. Apart from indicating the general course of progress any pronounced dip or sudden rise is likely to reflect a potent factor which is common to the group or squad of players. For young sportspeople, as with workers in industry, the graph can be a powerful motivational device in that it presents a graphic, objective description of improvement.

Smooth curves of learning, such as in Figure 1, only occur for large groups of people and result from the averaging out of individual performance scores. For a single individual a learning curve seldom rises smoothly for successive practices. Whilst a general upward trend can frequently be seen, individual learning curves are characterized by a great deal of zigzagging. In the course towards becoming a highly skilled sportsman there are inevitable fluctuations in performance and there are periodic surges and setbacks. Fluctuations in performance occur because of the numerous factors such as motivation, health, concentration among others which serve to influence learning. Some factors facilitate skill acquisition whilst others inhibit improvement. These factors can operate in various ways from one practice session to another and from one match to another. Fluctuations in performance therefore arise because of variations which occur in the factors involved and the way they may interact with each other. On some days a games player for example, feels confident, is seeing the ball and everything is going well for him/her. On other days he/ she may not be concentrating so well, his/her attention wanders and he/she becomes anxious and depressed about his/her play. These temporary mood swings occur for most players at some time and their cause is not always easy to ascertain.

Motivation is discussed at length in the following section but the use by the coach of individual learning curves can be of considerable motivational value. They provide graphic, objective and measurable evidence of a player's progress. Any progress which a player makes is there for him/her to see and this information is a powerful incentive to continue his/her efforts in trying to develop his/her ability. Charts of progress also provide the opportunity to use a good motivational technique which is to compete against oneself. That is to say a player can compete against his/her previous performances. Charts are a source of valuable information for they enable the player to relate his/her performance to his/her preparation for that performance. In this way he/she is able, with experience, to select the most effective approach to make. In tennis graphs can be drawn up to indicate progress with the service and other strokes in terms of their accuracy, control and consistency. Graphs of test results from physical fitness measures can also be outlined.

Generally, it is the results of matches which are taken as being the measure of a player's progress. This can be a very inaccurate yardstick and there are several reasons for this fallibility. In many cases the margin between a win and a loss can be very close indeed as is evidenced by matches which are won on the tie-break in tennis. Again parts of a player's game may be undergoing improvement but this improvement has still to be reflected in match and tournament performance in terms of results. Further tennis players, for example, can be winning at junior level with the sort of game which will certainly not succeed at senior international level which has been a characteristic of the game in this country for decades. Players who take a long-term view and go for big powerful strokes and a generally ambitious game may lose out at junior level but if they have the courage of their convictions, with increasing mastery they will do best in the end. Through lack of early success, however, they may become despondent and give up. Charts which provide valid measures of progress in terms of skilled performance measures should encourage them to continue.

Motivation

Motivation can be defined as being aroused to action, to directed purposeful behaviour although this may not necessarily be either efficient or effective. The study of motivation is important because it seems fairly certain that with the exception of the few champions in sport the majority of young players seldom fulfil their potential. Given the opportunity most young players could do much better. This is true for all sports and not just tennis and arises in the main from motivational problems.

In sportsmen as in other spheres of skill acquisition improvements in performance tend to decrease as the limits of ability are approached. This is partly due to the fact that there is a slowing down in the rate at which people are able to continue to improve. At moderate levels of ability progress can readily be seen and is sometimes quite marked. At the higher levels of performance, however, much of the time spent in practice will be spent solely in maintaining these levels. As players continue to improve this tends to be true to a progressively greater extent with more and more of a player's practice time being spent in maintaining standards. Thus at relatively high levels of play it takes more effort, more time to improve further and it becomes increasingly difficult to make progress. Indeed once champion players drop out of any sport for any length of time the old adage: ‘They never come back’ holds true for most. In so many cases a return to the game is at a lower standard than formerly.

For the aspiring player the problem sooner or later becomes largely one of motivation. In many cases there is the belief that further improvement is simply not possible. If a player now perceives that this is also the belief of the coach then it is highly likely that these expectations of his limits will be confirmed. As we have noted earlier, the coach's expectation of performance is a powerful factor determining performance levels and has led to much research outside sport concerning the so-called self-fulfilling prophecy. Generally a person's performance tends to confirm the expectations of ‘significant others’ or those who are perceived as having some credibility. Thus an optimistic approach by a coach or teacher tends to arouse higher motivational levels and expectations in the player and a pessimistic approach to result in a lowering of motivational levels and of expectations.

Many players experience periods when they become convinced that they have reached the limits of performance and that further improvement is simply not possible. An optimistic, insightful and supportive coach has a crucial role to play in encouraging the player to persist at such times and to tackle difficulties in a positive way. Players can be helped if it is pointed out that temporary halts to progress are not uncommon in the acquisition of skill in sports. The coach can point out that latent learning can be taking place which is not immediately reflected in performance measures.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and a combination of these two are the only forms which motivation can take. Extrinsically motivated people are engaging in a particular activity or sport for the rewards which go with success. They are playing for the status of being in a team or squad or they are playing for the medals, cups or the financial rewards which can be obtained. On the other hand, when a person is intrinsically motivated he/ she is engaging in the sport for its own sake, for the satisfaction, for the sheer enjoyment that it brings. Many of the top players in sport get tremendous satisfaction from having complete mastery over a skill and being able to perform it in expert fashion. They are not satisfied with moderate standards and go to great lengths to become perfectionists for the personal satisfaction which this brings. They enjoy the challenge of the pursuit of excellence. Intrinsic motivation is generally associated with greater persistence and greater commitment. For people who are essentially extrinsically motivated to play sport that is, they are concerned mainly with the rewards which accompany achievement, then if the rewards become difficult to achieve or unobtainable they may well lose interest. The real danger also exists that where people are encouraged to play by being offered rewards they may sense that they are being manipulated, that other people are controlling their behaviour. It does happen that people who were initially intrinsically motivated lose this interest on being offered rewards and prizes. On the other hand a reward could be perceived by a person as increasing the importance of a particular achievement so that it becomes more prestigious than formerly. With greater feelings of personal competence intrinsic motivation is likely to be enhanced.

The following example illustrates how the introduction of rewards can cause a change from intrinsically to extrinsically motivated behaviour.

An old man lived alone on a street where boys played noisily every afternoon. One day the din became too much, and he called the boys into his house. He told them he liked to listen to them play, but his hearing was failing and he could no longer hear their games. He asked them to come around each day and play noisily in front of his house. If they did, he would give them each a quarter. The youngsters raced back the following day and made a tremendous racket in front of the house. The old man paid them, and asked them to return the next day. Again they made noise, and again the old man paid them for it. But this time he gave each boy only 20 cents, explaining that he was running out of money. On the following day, they got only 15 cents each. Furthermore, the old man told them, he would have to reduce the fee to five cents on the fourth day. The boys became angry, and told the old man they would not be back. It was not worth the effort, they said, to make a noise for only five cents a day.

(Casady, 1974)

Contrary to popular belief young players place great importance on being really good at a sport and not just on winning. It is important, therefore, that situations are created which give the young player the opportunity to develop his ability to pursue excellence. In the section which follows strategies for enhancing the intrinsic motivation of players are outlined.

How to Motivate Young Sports People

Several well-established motivational strategies can be employed to encourage young people to persist with their practice and training over extended periods of time. People differ markedly in their personalities, abilities and past experiences to the extent that they just cannot be treated all in the same way. Differences in personality, for example, mean that harsh criticism might be accepted by...