1

INTRODUCTION1

Geoffrey Parker and Lesley M.Smith

I

HISTORIANS AND THE ‘GENERAL CRISIS’

In 1642 John Goodwin, a pamphleteer, predicted that ‘the heate and warmth and living influence’ of the English House of Commons in their struggle with King Charles I ‘shall pierce through many kingdoms greate and large, as France, Germany, Bohemia, Hungaria, Polonia, Denmarke, Sweden and many others’. One year later Jeremiah Whittaker, a preacher, reassured the same assembly that it did indeed not stand alone in rebellion: ‘These are days of shaking and this shaking is universal: the Palatinate, Bohemia, Germania, Catalonia, Portugal, Ireland, England.’ In 1654, with the king executed and all his adherents defeated, John Milton imagined ‘that from the columns of Hercules to the farthest borders of India, I am bringing back, bringing home to every nation, liberty so long driven out, so long an exile’.2 Interest in international affairs by no means remained confined to those at the centre of the English Revolution. Between 1652 and 1664 Ralph Josselin, the vicar of the village of Earls Colne in Essex, often sat down on the eve of his birthday to record the ‘great actions’ of the previous year in both Britain and Europe. His survey on 25–6 January 1652 (to take but one example) reveals the speed with which the tremors of revolution abroad reached even a small community. Having summarized Cromwell’s successful campaigns in England, Scotland and Ireland, Josselin continued:

France is likely to fall into flames by her owne divisions; this summer shee hath done nothing abroad. The Spaniard hath almost reduced Barcelona, the chiefe city of Catalonia, and so that kingdome; the issue of that affair wee waite. Poland is free from warre with the Cossacks but feareth them. Dane and Suede are both quiet, and so is Germany, yett the peace at Munster is not fully executed: the Turke hath done no great matter on the Venetian, nor beene so fortunate and martial as formerly, as if that people were at their height and declining rather.3

Foreign observers showed equal awareness of the unusually widespread political instability of the mid-seventeenth century. Writing early in 1643 some friends of the count-duke of Olivares, the disgraced chief minister of Philip IV of Spain, noted a global context for the failures of their hero in the apologetic tract, Nicandro:

All the north in commotion… England, Ireland and Scotland aflame with Civil War… The Ottomans tearing each other to pieces… China invaded by the Tartars, Ethiopia by the Turks, and the Indian kings who live scattered through the region between the Ganges and the Indus all at each other’s throats.4

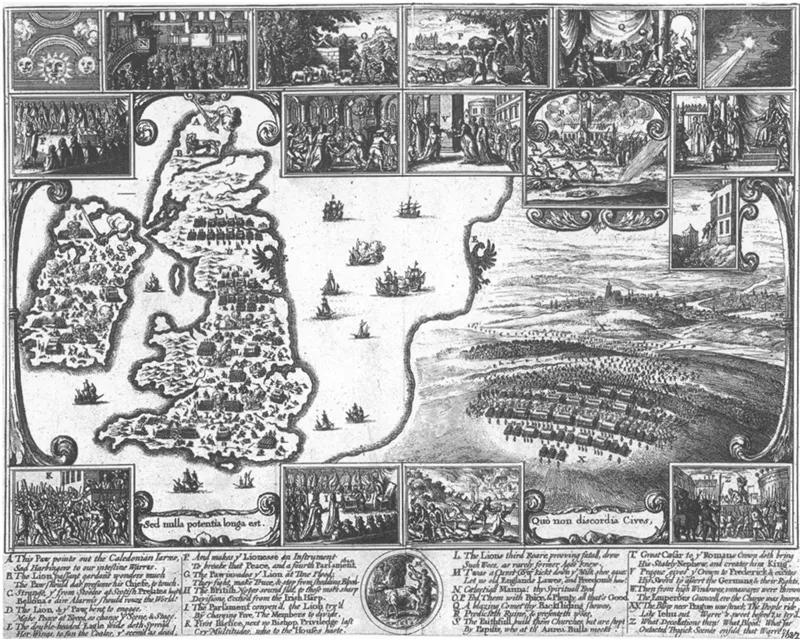

A few years later, a Scottish exile in France, Robert Mentet de Salmonet, prefaced his account of the English Revolution with the general statement that he and his fellow Europeans were living in an ‘Iron Age’ that would become ‘famous for the great and strange revolutions that have happen’d in it… Revolts have been frequent both in East and West.’5 Others attempted explicit comparisons: in 1642–3 the Czech Wenceslaus Hollar engraved ‘A comparison of the English and Bohemian Civil Wars’ (see Figure 1.1); in 1653 the Italian Giovanni Battista Birago Avogadro published a volume of studies that covered the uprisings in Catalonia, Portugal, Sicily, England, France, Naples and Brazil (based on information drawn from the reports published in newspapers such as the Mercure François); while in 1669 the Dutchman Lieuwe van Aitzema drew parallels between the Naples uprising of 1647 and the Moscow revolt of 1648. 6 By the 1660s, however, Thomas Hobbes could already see that the mid-century troubles, although memorable, remained isolated. His Behemoth, a personal account of the civil war, began with the words, ‘If in time, as in place, there were degrees of high and low, I verily believe that the highest time would be that which passed between the years l640 and 1660.’7

Voltaire, the philosopher, writer and all-purpose luminary of the French Enlightenment, was apparently the first person to see the events of mid-seventeenth- century Britain and Europe as part of a global crisis. In 1741–2 he composed a history book, Essai sur les mæurs et l’esprit des nations, for his friend, Mme du Châtelet, who was bored stiff by the past. The seventeenth century, with its numerous revolts, wars and rebellions, presented Mme du Châtelet with special problems of ennui and, in an attempt to render such anarchy more palatable, Voltaire advanced a theory of ‘general crisis’. Having grimly itemized the political upheavals in Poland, Russia, France, England, Spain and Germany, he turned to the Ottoman Empire where Sultan Ibrahim was deposed in 1648. By a strange coincidence, he reflected:

This unfortunate time for Ibrahim was unfortunate for all monarchs. The crown of the Holy Roman Empire was unsettled by the famous Thirty Years’ War. Civil war devastated France and forced the mother of Louis XIV to flee with her children from her capital. In London Charles I was condemned to death by his own subjects. Philip IV, king of Spain, having lost almost all his possessions in Asia, also lost Portugal.

Figure 1.1 A comparison of the English and Bohemian Civil Wars

Source: R.T.Godfrey, Wenceslaus Hollar: A Bohemian Artist in England (New Haven, CT, 1994), p. 92.

Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. (© British Museum)

The mid-seventeenth century, Voltaire concluded, constituted ‘a period of usurpations almost from one end of the world to the other’; and he pointed not only to Cromwell in Europe but also to Muley-Ismail in Morocco, Aurangzeb in India and Li Tsu-Ch’eng in China.8

This ‘world dimension’ lay at the centre of Voltaire’s whole Essai, and he returned to it later on, positing an almost organic theory of change.

In the flood of revolutions which we have seen from one end of the universe to the other, there seems a fatal sequence of events which dragged people into them, just as winds move the sand and the waves. The developments in Japan offer another example.

And so he continued, writing one of the earliest—and most readable—genuinely global histories ever composed.9

Voltaire perceived an important feature of the General Crisis that many subsequent writers have forgotten: the phenomenon did not remain confined to Europe.10 On the whole, his twentieth-century successors have proved less inclusive. Paul Hazard portrayed this period as one of fundamental change in his 1935 classic La Crise de la conscience européenne, but restricted his attention to Europe. Three years later the concept passed from the history of ideas to politics and economics in Roger B.Merriman’s Six Contemporaneous Revolutions (Oxford, 1938) but again only the major European upheavals of the 1640s featured. In 1954, E.J.Hobsbawm’s long article, ‘The crisis of the seventeenth century’ (Past and Present, V and VI, 1954), reviewed the problems of the European economy and postulated the existence of a ‘general crisis’ there too.However, Woodrow W.Borah’s New Spain’s Century of Depression (Berkeley, 1951) examined the economic crisis in seventeenth-century Mexico, and related it to developments in Europe; while Roland Mousnier’s Les XVIe and XVIIe siècles (Paris, 1954) characterized the history of the entire world between 1598 and 1715 as a ‘century of crisis’, with demographic, economic, political, diplomatic and intellectual manifestations affecting all the major civilizations.11

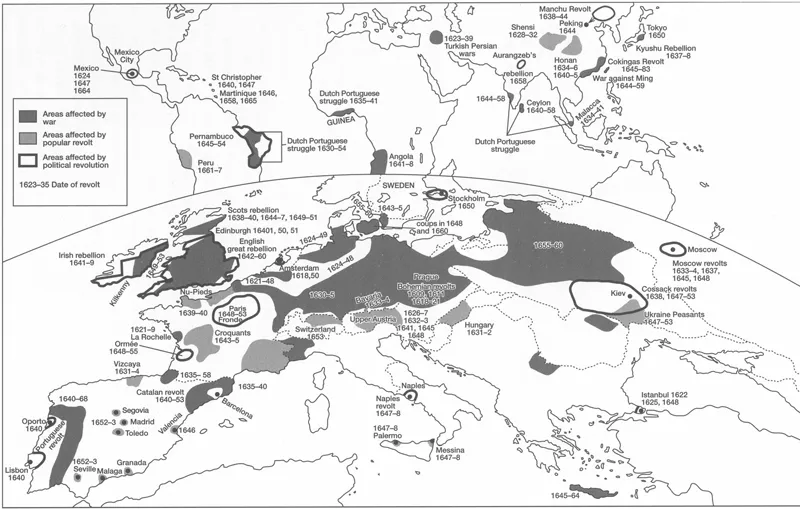

Hobsbawm’s essay stimulated a host of equally Eurocentric articles in Past and Present, most of them republished in T.S.Aston (ed.), Crisis in Europe, 1560–1660 (London, 1965). Then came a challenging survey by T.K.Rabb, The Struggle for Stability in Early Modern Europe (Oxford, 1976); a special issue of the journal Revue d’histoire diplomatique (Paris, 1978), containing eleven case studies; and an issue of the journal Renaissance and Modern Studies (Nottingham, 1982) on ‘“Crisis” in Early Modern Europe’, with eight more articles. Finally, at the 1989 meeting of the American Association for Asian Studies, four papers on ‘The General Crisis in East Asia’, published in 1990 in Modern Asian Studies, belatedly restored the world dimension to the General Crisis debate.12 For, as Figure 1.2 shows, upheavals and rebellions occurred in almost all areas of the Old World, and also in some parts of the New.

Figure 1.2 The ‘General Crisis’

In fact, simultaneous global unrest had happened before. About the middle of the second millennium BC several pre-classical civilizations of Eurasia (Minoan Crete, Mycenaean Greece, the Egyptian Middle Kingdom) collapsed; in the fourth and fifth centuries AD the main classical civilizations foundered almost at the same time (the Chin, Gupta and Roman empires); and in the fourteenth century, even before the Black Death, the leading states of the High Middle Ages either tottered or crumbled (the Yüan in China, the Minamoto in Japan, the Ghazni in India, the feudal monarchies in Europe).13 At least one more such ‘general crisis’ took place after the seventeenth century: between 1810 and 1850 (see p. 22).

This pattern of world-wide upheaval suggests that beneath the more obvious local precipitants lurked very basic global causes. The most plausible candidate is climatic change: a world-wide deterioration in prevailing weather patterns, leading to relative over-population and related food shortages, to mass migrations (perhaps armed) from poorer to richer lands, to swiftspreading pandemics, and to frequent wars and rebellions. However, for a climatic explanation to be valid, evidence of crisis must be apparent in many parts of the globe—at least over large parts of the northern hemisphere (where the bulk of the world’s population then lived)—and not merely in a small region such as Europe. The mid-seventeenth century seems to meet this criterion. The peasant revolts in Ming China between 1628 and 1644 resembled the simultaneous wave of popular uprisings in France under Richelieu; increasing military expenditure and court extravagance at a time of economic adversity characterized both societies; and both in Peking in 1644 and in Paris in 1648 ‘usurpers’ (to use Voltaire’s phrase) eliminated a sovereign of undisputed legitimacy. Disastrous plague epidemics also ravaged both countries—1639–44 in China; 1630–2 and 1647–9 in France—and numerous sources across Eurasia recorded climatic deterioration.14

Nevertheless, the transition from world economic crisis to individual political upheavals depended upon personal decisions, local conditions and unforeseen accidents to a degree that makes generalization hazardous. The General Crisis in fact comprised two related elements: on the one hand, a major hiatus in the demographic and economic evolution of the world which increased the probability that political tensions would escalate into violence; on the other, a series of political crises, some of which developed into revolutions while others did not. Since the links between the two were neither simple nor obvious, it is prudent to remember the advice of John Selden, the seventeenth-century wit, cynic and antiquarian, to those who were overzealous in bringing witches to trial: The reason of a thing is not to be enquired after,’ he warned, ‘’til you are sure the thing itself is so. We are commonly at what’s the reason of it? before we are sure of the thing.’15 In the case of the General Crisis, to ensure that we have understood the ‘thing’ aright, it is prudent to study the economic and political developments separately before examining the links between them.

II

AN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CRISIS

Most historians know about the ‘Little Ice Age’, once parochially described in English school textbooks as ‘the time the Thames froze’. The problem has always been to explain it. The work of an American astronomer, John Eddy, on the scarcity of sunspots during the late seventeenth century (the so-called ‘Maunder Minimum’) suggests an important new explanation for the phenomenon (see Chapter 11). The leading astronomers of the late seventeenth century—including Johan Hevelius (1611–87) in Poland, G.D.Cassini (1646– 1712) in France and John Flamsteed (1646–1719) in England—all recorded an almost complete absence of sunspots between about 1645 and 1715, while noting that their predecessors Galileo and Scheiner had observed them earlier in the century. These skilful European astronomers also failed to see either aurora borealis (northern lights) or a corona ...