![]()

Chapter 1

Structural change

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The development of an economy is characterised by changes in the structure of economic activity. Some sectors of the economy grow faster than others so that over time there are marked changes in their relative importance. The causes of such change are complex but include: changes in the pattern of demand; the invention of new products and processes; the different opportunities across sectors for technical progress and factor substitution; the changing importance of the role of government in economic activity, and the changing patterns of international competitiveness.

This chapter first considers, in section 1.2, certain systematic changes that tend to occur in the sectoral distribution of activity as economies develop, and draws attention in particular to the long-run growth in services. It then goes on in section 1.3 to consider some important implications of the tendency for productivity growth in many areas of service activity, especially the caring and nurturing services such as health and education, to lag behind that in the rest of the economy. This is followed in section 1.4 by an examination of trends in manufacturing activity, and addresses such questions as why manufacturing activity has declined in importance so much more in the UK than in the other major industrial countries, what the importance is of this relative decline, and why it has happened.

1.2 LONG-TERM CHANGES IN SECTOR SHARES

In the following discussion there will be frequent references to ‘industry’, ‘goods’ and ‘services’. These categories of activity are defined as follows. Industry is made up of mining and quarrying; manufacturing; gas, electricity and water; and building and construction. These plus agriculture, forestry and fishing make up the goods sector of the economy. The service sector includes all other activities—transport and communications; distribution; insurance, banking and finance; professional and scientific services; hotels and catering; central and local government; and miscellaneous services.

One general feature which seems to fit the historical experience of all developed economies is a movement of resources out of agriculture into non-agricultural activities, followed by a shift from industry into services. In somewhat more detail the following main stages may be identified. In the first stage of development a high proportion of employed labour is attached to the land. As development proceeds there is a movement out of agriculture into industry and services but especially into the former. Service activity also expands because of the linkages between industry and services—most obviously transport, distribution and finance. Both industry and services will therefore tend to increase in relative importance. Eventually industry’s share of total employment stabilises but services continue to expand in relative importance at the expense of agriculture. The final stage is when an economy reaches maturity. During this phase of development the service sector’s share of activity continues to expand but now at the expense of industry, which declines in relative importance. If services are to continue to expand in relative importance then, in the absence of growth in the total employed labour force and with agricultural employment reduced to a very low level, this expansion can occur only at the expense of industry.

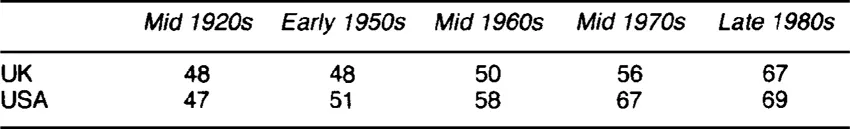

There is an abundance of empirical evidence to support these general structural changes that accompany development. Take for instance agriculture’s share of total employment. In the UK of the 1850s this stood at around 20 per cent; by the 1920s it had fallen to less than 10 per cent and today it stands at around 2.5 per cent. For the USA the approximate figures for the same periods were 60 per cent, 20 per cent and 3.5 per cent respectively. Turning to the division between goods and services we find that the share of employment in the service sector has displayed a long-term upward trend, as is shown by the figures for the UK and USA given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Service sector share of total employment, UK and USA (%)

Sources: Kuznets (1977); OECD, Labour Force Statistics, Paris, 1988

Even though all developing economies may in the fullness of time experience similar long-term changes in employment patterns, at a particular point in time they are likely to be at a different stage in the development process, This may be due to the fact that industrialisation started earlier in some countries than in others or because countries spend different periods of time in a particular stage of development. Take, for instance, the position in the mid 1960s. At this time the UK had less than 4 per cent of its employed labour force in agriculture and the USA less than 6 per cent. This compares with about 10 per cent for West Germany, 17 per cent for France and over 20 per cent for Japan and Italy. There was much less scope in the UK and USA therefore for industry to benefit from a transfer of labour out of agriculture than was the case for the other countries. This would be a matter for concern if the performance of the economy depended to a significant extent on an increase in the supply of labour to the industrial sector; we return to this argument later. Another interesting feature of the UK economy in the mid 1960s is that the service sector’s share of employment had changed little since the 1920s, while in the USA services had grown steadily in relative importance. In the UK the goods sector’s share of employment remained at a relatively high level for a longer period of time than was the case in the USA. The slower movement of manpower into services in the UK over the 40-year period up to the mid 1960s may in part be explained by the greater effect on the UK of industrial reconstruction following the two world wars. It is also likely to be due in part to the slower rise in living standards in the UK and also in part to the poor productivity performance of UK industry.

To the underlying secular forces affecting sector shares must be added shorter-term influences which may reinforce or weaken the underlying trend. These influences often come in the form of severe shocks to the economy. For instance, during the interwar years the high level of unemployment was a factor accounting for an increase in the proportion of UK labour employed in services. Some of the surplus labour of this period was taken up as underemployed labour in low-paid services industries—not only as low-wage employees but also as low-paid self-employed workers. During the war and immediate postwar years however these manpower movements were reversed. Again, the shock to the manufacturing sector resulting from the macroeconomic policies of the incoming Thatcher administration in 1979 served to strengthen the underlying movement of manpower away from industry into services.

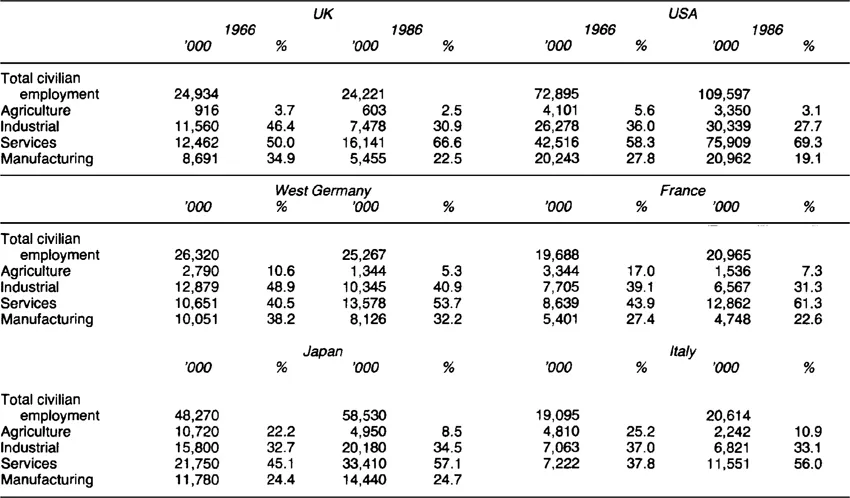

Whatever the nature of the short-run movements in sector shares, the underlying long-term trends are inescapable. Two of the clearest of these trends are the decline in manufacturing and the growth of services. A summary of these trends for six major industrial countries over the period 1966–86 is given in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Civilian employment, UK and USA, 1966 and 1966

Source: OECD, Labour Force Statistics, Paris, 1998

What economic explanation can be offered for these long-term movements? Both supply—and demand-side factors are at work. Consider first the decline in the relative importance of agriculture. On the supply side, big gains in productivity have been made as a result of increased mechanisation, improved transportation, the greater use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, and a general improvement in scientific knowledge and farm-management techniques. The productivity performance of the agricultural sector compares favourably with that of industry. For instance, over the period 1959–74 the volume of agricultural output in the UK increased by about 56 per cent, the same increase as in manufacturing. Over the same period employment declined slightly in manufacturing but by a substantial amount in agriculture, indicating that labour productivity increased faster in agriculture over this period than in manufacturing. No problem of labour reallocation would arise if these supply-side changes were counter-balanced by an increase in the demand for agricultural produce. However, as income per head rises so the income elasticity of demand for food declines. A combination of good productivity performance and falling income elasticity of demand tends over time to generate surpluses. As a result, farm prices and profitability and the wages of farm labourers fall relative to those elsewhere in the economy thus inducing a shift in resources. Alternatively, or in addition, the labour market adjustment mechanism may take the form of labour being forced to move away from agriculture because of few job opportunities at the going wage rates.

The growing importance of services can also be explained by a combination of supply—and demand-side factors. Early explanations placed the main emphasis on demand: the high income elasticity of demand for services as compared with goods at high levels of real income per head means that as an economy becomes more prosperous an increasing proportion of additional income tends to be spent on services. However, subsequent research on US data suggested that only a small part of the growth of service sector employment could be attributed to these demand-side forces, estimates of income elasticities of demand being rather similar for many kinds of goods and services. On reflection this is hardly surprising since many goods and services are closely linked. The growth in importance of travel, leisure and entertainment, for instance, involves expenditure on goods as well as services.

The main explanation for the growing importance of the service sector must therefore be found on the supply side. Here the main force accounting for changes in the pattern of employment is the difference between sectors in long-run productivity performance. On average, the rate of increase in labour productivity tends to be lower in services, both because of fewer opportunities for replacing labour with capital and because of a lower rate of technical change. As a result the service sector’s share of employment must increase. It is worth noting that a lower rate of productivity growth for services implies that the prices of services will tend to increase more quickly than those for goods. This will offset part of any tendency for the demand for services to rise more quickly because of a higher income elasticity of demand. Overall, therefore, there may be even less of a difference in the growth rates of demand in the two sectors than might be suggested by a comparison of income elasticities of demand alone. All this suggests that changes in sector shares should be more noticeable in terms of employment than in terms of the volume of output.

Another supply-side explanation for the growth of services relates to shifting comparative advantage in international trade. The reasoning here is that, as industrial wages increase with the level of prosperity, comparative advantage in production switches to low-wage underdeveloped countries. In the richer countries, comparative advantage moves in the direction of professional services which, though intensive in labour are intensive in labour of high skill and expertise, which is lacking in the less developed countries. One problem with this explanation is that it may underestimate the extent to which any such tendency for comparative advantage to shift can be offset by the continual introduction of new products and processes which are also intensive in the skilled labour which is lacking in less-developed economies. The emergence of new industrialising countries may, that is, result in an overall expansion of world trade with little or no adverse effects on industrial employment in advanced countries. However, if the new industries which replace the old are less labour intensive, a net loss of labour will occur. Empirical work in this area suggests that the net displacement effect on labour in the advanced countries is small.

1.3 SERVICE SECTOR PRODUCTIVITY

The previous section pointed to the relatively low average productivity growth rate for service activities as a major factor explaining this sector’s growing share of employment. It is important to note, however, that this is an average result and that within the service sector there are wide variations in productivity performance, and that productivity gains in some service activities may exceed those in manufacturing. This is most likely in areas such as communications, banking, insurance and finance, where there is substantial scope for technical progress and factor substitution.

In other areas, such as hotels, catering, health, education and public administration, productivity gains are more difficult to achieve. One problem to be noted at the outset is that of obtaining reliable productivity indices for many of these service activities and in particular of finding reliable indicators of output. As will be suggested later, some of the available productivity indices are at best incomplete and may be quite misleading for judging performance. It is with these service activities of low measured productivity growth that this section is mainly concerned.

One possible reason for poor productivity performance is of course that labour is used inefficiently. This is a serious possibility because many services, especially those in the public sector, do not face the competitive discipline of the market place. Some exposure to competitive forces or, where this is not feasible, the discipline of periodic efficiency audits may have beneficial effects. But the main point to emphasise is that, even if there is no noticeable inefficiency, labour productivity will still lag behind that of the rest of the economy because of fewer opportunities for labour-saving investment and technical change. Take for instance the caring and nurturing services—health and education. Over the period 1974–85 the average rate of growth in output per person employed for the UK as a whole was 2.5 per cent per annum. In education and health, on the other hand, various crude measures of labour productivity showed a decline. The pupil—teacher ratio fell slightly and health productivity indicators such as the number of new outpatients per medical staff member also declined.

Although productivity growth in these services lags behind the rest of the economy, the same is not true, or at least not true to the same extent, of wage and salary movements. Over the long run, wages and salaries must keep broadly in line with those on offer elsewhere if labour is to be kept and additional labour attracted as the services expand. This has important cost and financial implications.

Low productivity growth, and wages which tend to keep in line with those offered elsewhere in the economy, mean that unit costs will tend to increase faster in services. A widespread response to rising relative costs has been to reduce direct contact between suppliers of services and their customers. The clearest examples of this are self-service and self-selection in retailing and driver-only bus services, but similar pressures exist in health and education. These developments draw attention to the inadequacy of commonly used productivity indices. Because of the difficulty referred to earlier of measuring output, they fail to take account of an important dimension of output—the quality of service. Crude productivity indices may show an increase at the same time as the quality of service is deteriorating. In hospitals, for instance, the number of patients discharged per consultant may increase but at the cost of discharging patients too quickly because of a shortage of beds. Some of these patients may have to be readmitted for further hospital treatment, which would further improve the crude productivity indicator. Another factor to mention is that the cost savings may reflect not greater efficiency, in the sense of reduced inputs of labour or capital, but merely lower wages for the workers concerned or harder work for the same pay.

In the public sector, low productivity growth and escalating costs explain why the provision of services has placed an increasing financial burden on central and local government. One response has been an attempt to increase efficiency by measures such as competitive tendering. This may lead to improvements in efficiency without any ...