1 Human emotions

Humans are, to say the least, highly emotional animals. We love and hate; we fall into suicidal depressions or experience moments of joy and ecstasy; we feel shame, guilt, and alienation; we are righteous; we seek vengeance. Indeed, as distinctive as capacities for language and culture make us, humans are also unique in their propensity to be so emotional. Other animals can, of course, be highly emotional, but during the course of hominid and human evolution, natural selection rewired our ancestors’ neuroanatomy to make Homo sapiens more emotional than any other animal on earth. Humans can emit and interpret a wide array of emotional states; and in fact, a moment of thought reveals that emotions are used to forge social bonds, to create and sustain commitments to social structures and cultures, and to tear sociocultural creations down. Just about every dimension of society is thus held together or ripped apart by emotional arousal.

These observations seem so obvious that it is amazing that for most of sociology’s history as a discipline, the topic of emotions was hardly mentioned. In recent decades, however, theory and research on emotions have accelerated in sociology and now represent one of the leading edges of inquiry in the discipline (see Turner and Stets, 2005; Stets and Turner, 2006, 2007 for reviews). There are now many theories, supported by research findings, that seek to explain emotional dynamics; and my goal in this book is to present yet another theory, although my approach attempts to integrate existing theories and research findings into a more global analysis of human emotionality.

What are emotions?

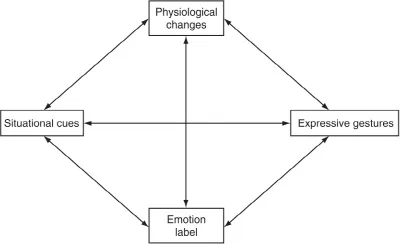

Surprisingly, a definition of our topic is elusive. Terms such as affect, sentiment, feeling, mood, expressiveness, and emotion are sometimes used interchangeably and at other times, to denote a specific affective state. For my purposes, the core concept is emotion, with other terms denoting varying aspects of emotions. What I propose, then, is a theory of human emotional arousal that seeks to provide answers to one fundamental, though complex, question: What sociocultural conditions arouse what emotions to what effects on human behavior, interaction, and social organization? Clearly, this one question is really a number of separate questions, each of which will be given a provisional answer in a series of abstract principles (see Chapter 9 for a summary). Still, I have not clearly defined by topic – emotions – nor will I be able to offer a general definition because depending upon the vantage point, the definition will vary. From a biological perspective, emotions involve changes in body systems – autonomic nervous system (ANS), musculoskeletal system, endocrine system, and neurotransmitter and neuroactive peptide systems – that mobilize and dispose an organism to behave in particular ways (Turner, 1996a, 1999a, and 2000a; as well as the appendix to Chapter 2). From a cognitive perspective, emotions are conscious feelings about self and objects in the environment. From a cultural perspective, emotions are the words and labels that humans give to particular physiological states of arousal. As Figure 1.1 outlines, Peggy Thoits (1990) sought to get around this vagueness by isolating four elements of emotions: situational cues, physiological changes, cultural labels for these changes, and expressive gestures. All of these are interrelated, mutually influencing each other, but simply denoting “elements” of emotions does not really provide a clear definition of our topic. For the present, then, a precise definition will have to elude us. We can get a better sense for the topic by outlining the varieties and types of emotions that are aroused among humans and that, as a consequence, lead them to think and act in particular ways.

Primary emotions

Primary emotions are those states of affective arousal that are presumed to be hard-wired in human neuroanatomy. There are several candidates for such primary emotions, as outlined in Table 1.1 where the lists of primary emotions posited by researchers from diverse disciplines are summarized (Turner, 2000a:68–9). Despite somewhat different labels, there is clear consensus that anger, fear, sadness, and happiness are primary; and indeed, humans probably inherited these not only from our primate ancestors but from all mammals as well. Disgust and surprise can be found on many lists, and we might consider these as primary as well. Shame and guilt can be found on several lists but, as I will argue shortly, these are not primary but, instead, elaborations of primary emotions. Other emotions like interest, anticipation, curiosity, boredom, and expectancy are less likely to be primary, and in fact, they may not even be emotions at all but, rather, cognitive states.

Figure 1.1 Thoits’s elements of emotions.

Humans have the capacity to arouse primary emotions at varying levels of intensity, from low- through medium- to high-intensity states. Table 1.2 summarizes my conceptualization of four primary emotions and their varying levels of intensity. As I will argue in Chapter 2, natural selection probably worked on the neuroanatomy of hominids and humans to increase the range of expression of these primary emotions. With this wider range, it becomes possible to expand further the subtlety and complexity of emotional feelings and expressions which, in turn, increase the attunement of individuals to each other. The terms in Table 1.2 are, of course, cultural labels and, as such, are part of an emotion culture, but in my view, these linguistic labels for variations in primary emotions are a surface manifestation of a basic neurological capacity. They are a kind of emotional superstructure to an underlying biological substructure; and what is true of variations in primary emotions is doubly true for combinations of these emotions.

Elaborations of primary emotions

First-order elaborations of primary emotions

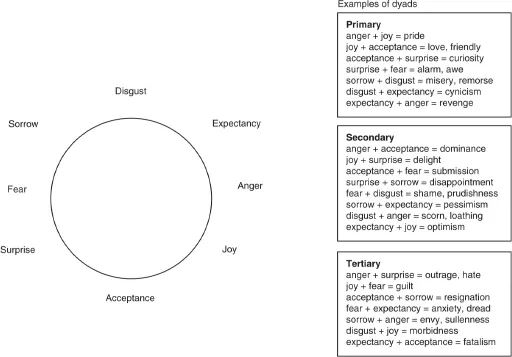

At some point in hominid and human evolution, natural selection worked on our ancestors’ neuroanatomy to create a new level of emotionality: the capacity to combine primary emotions. Plutchik (1962, 1980) was one of the first researchers to posit a way to conceptualize how emotions are “mixed” to produce new emotions. For Plutchik, primary emotions are much like primary colors and can be conceptualized on an “emotion wheel,” with the mixing of relatively few primary emotions generating many new kinds of emotions. The basic elements of his scheme are portrayed in Figure 1.2.

When emotions are combined, new kinds of emotions appear, just like mixing primary colors. I prefer to conceptualize this “mixing” as elaborations. Just how this elaboration is done neurologically is not so clear, but it probably involves the simultaneous activation of primary emotion centers in the subcortical parts of the brain in ways that produce new kinds of more complex emotions. In my conceptualization, a first-order elaboration of primary emotions involves a greater amount of one primary emotion “mixed” with a lesser amount of another primary emotion (in some unknown neurological way). The result is a new emotion that can further refine individuals’ emotional feelings, expressions, and attunement.

Table 1.1 Representative examples of statements on primary emotions

Figure 1.2 Plutchik’s model of emotions.

Note

Primary, secondary, and tertiary emotions are created by “mixes” of emotions at varying distances from each other on the wheel above. A primary emotion is generated by mixing emotions that are adjacent to each other,a secondary by emotions once removed on the wheel, and a tertiary by emotions at least twice removed on the wheel.

Table 1.2 Variants of primary emotions

Table 1.3 outlines the first-order elaborations for the four primary emotions outlined in Table 1.2 (Turner, 1996a, 1999a, 2000a). Thus, for example, a greater amount of satisfaction-happiness combined with a lesser amount of aversion-fear generates new emotions like wonder, hopeful, relief, gratitude, and pride (see top of Table 1.3), or a greater amount of aversion-fear mixed with a lesser amount of satisfaction-happiness generates emotions like awe, veneration, and reverence. Similar kinds of new emotions appear for all of the other combinations of primary emotions.

Table 1.3 First-order elaborations of primary emotions

Table 1.3 outlines the first-order elaborations for the four primary emotions outlined in Table 1.2 (Turner, 1996a, 1999a, 2000a). Thus, for example, a greater amount of satisfaction-happiness combined with a lesser amount

As I will argue in the next chapter, natural selection hit upon this solution to enhancing emotionality for two critical reasons. First, as evolved apes, humans do not have strong herding, pack, pod, or group “instincts” or behavioral propensities; tight-knit groups are not natural social formations for an ape (for monkeys, to be sure, but not apes; see Maryanski and Turner, 1992; Turner and Maryanski, 2005). Hence, by increasing hominids’ and then humans’ emotionality, a new way to generate stronger social bonds became possible; and once emotions proved to be a successful adaptation, natural selection continued to enhance this capacity.

Second, three of the four primary emotions are decidedly negative and work against increased social solidarity (and, if we add other primary emotions from the list in Table 1.1, the proportion of negative primary emotions only increases). Fear, anger, and sadness are not, by themselves, emotions that bind individuals together; and so, if emotions were to be used to forge social bonds among hominids and eventually humans, the roadblock presented by a bias of emotions toward the negative had to be overcome (Turner, 2000a). One “solution” hit upon by natural selection was to combine negative emotions with satisfaction-happiness to produce emotions that could work to create tighter-knit social bonds. For instance, wonder, hopeful, relief, gratitude, pride, appeased, calmed, soothed, relish, triumphant, bemused, nostalgia, hope, yearning, awe, reverence, veneration, placated, mollified, acceptance, and solace can all potentially forge social bonds and mitigate the dis-associative power in the negative emotions. However, other more dangerous emotions such as vengeance and righteousness are also generated by combinations of anger and happiness; and these emotions can fuel violence and disruption of social bonds. Another solution to the predominance of negative primary emotions was for natural selection to work on the neuroanatomy of hominids and humans to combine two negative primary emotions in ways that reduce the “negativity” of each of the two emotions alone and, as a result, produce new emotions that are less volatile. Still, as the combinations of two negative emotions in Table 1.3 reveal, many of these new kinds of emotions are also highly negative, although some call attention to another’s plight. For example, dissatisfied, sullenness, forlornness, remorseful, and melancholy are generated by disappointment-sadness combined with a lesser amount of fear or anger, and, perhaps, these emotions would encourage supportive behaviors to re-establish social bonds. Other combinations can be used to sanction negatively those who have broken social bonds and/or violated the moral order, thus turning a negative combination into an emotional response that has some potential for reestablishing the social order. Yet, many of these emotions such as wariness, envy, repulsed, antagonism, bitterness, betrayal, jealousy, suspiciousness, and aggrieved can also work to disrupt bonds.

Second-order elaborations of primary emotions

First-order emotions alone, then, could not fully mitigate against the power of negative emotions to disrupt the social order, and so I believe that natural selection further rewired the human neuroanatomy (and perhaps our immediate hominid ancestor’s) to generate what I term second-order elaborations that are a mix of all three negative emotions (Turner, 2000a). As Table 1.4 outlines, I see shame, guilt, and alienation as combinations of the three negative emotions. The dominant emotion is disappointment-sadness, with lesser amounts of anger and fear in different proportions. Shame is an emotion that makes self feel small and unworthy; and it generally emerges when a person feels that he or she has not behaved competently or met social norms for expected behaviors. Shame is mostly disappointmentsadness at self, followed in order of magnitude by anger at self, and fear about the consequences to self of incompetent behaviors. Shame is a powerful emotion for social control because it is so devastating, with the result that people try to avoid behaving incompetently and violating norms. Thus, shame operates to sustain patterns of social organization and gives negative sanctions “teeth” because such sanctions activate shame, thereby motivating individuals to change their behaviors.

Table 1.4 The structure of second-order emotions: shame, guilt, and alienation

However, shame is so negative that it often activates defense mechanisms and repression (see Chapter 4), with the result that the repressed emotions transmute into one or more of their constituent emotions – most often anger (Tangney et al., 1992) but at times deep sadness and high anxiety or fear. These transmutations of shame can, in turn, disrupt social bonds. Still, with shame as an emotional response, people will generally monitor their own behaviors and act in ways to avoid experiencing such devastation to self.

Guilt is an emotion that combines disappointment-sadness with fear about the consequences to self and anger at self for violating moral codes. Unlike shame, guilt tends to be confined to specific actions and, unless chronic, does not attack a person’s whole self (Tangney and Dearing, 2002; Tangney et al., 1996a, b, 1998). People see that they have committed a “moral wrong” and are generally motivated to change their behavior so as to avoid experiencing guilt (Turner and Stets, 2005). Yet, if guilt is chronic and is activated in violation of powerful moral codes, such as the incest taboo, it too may be repressed, thereby making it more likely that one of its constituent primary emotions will surface – typically in the case of guilt, intense fear and anxiety but also depression. Still, guilt like shame mitigates the power of each of the three negative emotions from which it is built and, in fact, creates an emotion that makes people aware of moral codes and willing to abide by them in order to avoid experiencing guilt.

Alienation is the third of these second-order elaborations and is, once again, mostly disappointment-sadness, anger at a situation or social structure, and fear about the consequences of not meeting expectations in this structure. Alienation does not promote high sociality, but it does transform negative emotions into a withdrawal response, reducing the level of commitment to, and willingness to participate in, social structures. Such an emotion does not promote solidarity, to be sure, but it does reduce the disruptive power of anger and, hence, is less disruptive than anger alone. Alienation is, as we will see, an important emotion in understanding how commitments to social structures and cultural codes are lowered.

Just when hominids could experience shame, guilt, and alienation is impossible to know. The evidence suggests that chimpanzees, with which we share 99 percent of our genes, do not experience guilt and shame as humans do (Boehm, n.d.(a)), and so these emotions may be relatively late evolutionary arrivals and, hence, may be uniquely human. These are particularly important emotional capacities for several reasons. First, as noted above, they mitigate against the power of any one of the three negative emotions to disrupt social relations and, in fact, transform these negative emotions in ways which, if not repressed, increase social solidarity. Second, they cause individuals to self-monitor and self-sanction themselves when they behave inappropriately and/or violate moral codes. Third, they operate as a motive force behind individuals’ efforts to repair breaches of social relations or violations of moral codes. And, fourth, they plug individuals into the culture of groups – its norms and its moral codes – and thereby provide the emotional energy behind efforts to conform to these moral codes. Without shame and guilt, social control would be difficult for a weak-tie primate, but once shame and guilt emerge as emotional responses, individuals become more attuned to each other, to the demands of social structures, and to the dictates of culture (Turner, 2000a). Indeed, without guilt and shame, human sociopaths would be far more common, and the viability of social structure and culture to control human behavior would be reduced.

By reading across and down Tables 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4, the words denote the range of human emotions.1 While we cannot precisely define what an emotion is, at least in generic terms, we can be highly specific about the affective states that are aroused by human neuroanatomy. Humans can experience this complex of approximately one hundred emotions with relative ease. If you doubt this, turn off the sound on a movie or television drama and, in most cases, you will be able to read the emotions expressed in face as well as body countenance, movement, and juxtaposition to keep track of the story line. If you add to this the inflections, fillers, and pitch of voice (as would be the case if you watched a movie in a language that you did not know), you would do even better in understanding what was going on. As I will argue in Chapter 2, the first hominid language was that of emotions. Emotions reveal both phonemes and syntax, and like a spoken language, the “language of emotions” unfolds in terms of phonemes strung together by a grammar. Some of this grammar is hard-wired because certain emotional expressions seem universal, particularly those marking primary emotions (Ekman, 1973a, b, 1982, 1992a, b, c; Ekman and Friesen, 1975; Ekman et al., 1972). Once we move to first-order and second-order elaborations, however, culture probably has a greater effect on the expression of emotions, just as it does for spoken language (since the vocabulary and grammar of languages differ). Yet, the earlier and more primal “language of emotions” is hardwired. We learn the language of emotions long before spoken language, and like spoken language, humans learn it within a window of neurological opportunity that passes by the age of 11 or 12. Once this window is closed, individuals will have difficulty reading the emotions of others or expressing their states of physiological arousal through auditory or body language.

Explaining human emotional responses

The study of the biology behind human emo...