- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Legal Framework of the European Union

About this book

The law of the European Union continues to increase in complexity, importance and momentum, and is having an increasing effect on the lives of every person living in Britain. This book provides a focus on EC Law.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Legal Framework of the European Union by Sukhwinder Bajwa,Leonard Jason-Lloyd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Historical Development

and Primary Sources of

European Union Law

The idea of a unified Europe arose in the aftermath of the horror and devastation of the Second World War.

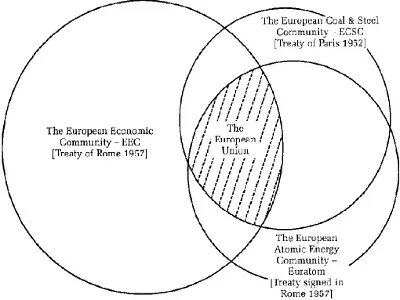

In order to avoid a repetition of such events, it made sense to pull together on a political and economic level in order to create a European community. The initial inspiration for a unified Europe came from a plan devised in 1950 by Robert Schuman (French Foreign Minister) and Jean Monnet, but it is generally accepted that the European Community’s most tangible origin was in 1952. It was during this year that a treaty was signed forming the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The participants in this agreement were France, West Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Italy. In 1957 these six nations formed two other mediums for economic co-operation, namely the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) and the European Economic Community (EEC). In effect, there are three European communities which now share the same basic institutional framework (see below).

In order to avoid a repetition of such events, it made sense to pull together on a political and economic level in order to create a European community. The initial inspiration for a unified Europe came from a plan devised in 1950 by Robert Schuman (French Foreign Minister) and Jean Monnet, but it is generally accepted that the European Community’s most tangible origin was in 1952. It was during this year that a treaty was signed forming the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The participants in this agreement were France, West Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and Italy. In 1957 these six nations formed two other mediums for economic co-operation, namely the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) and the European Economic Community (EEC). In effect, there are three European communities which now share the same basic institutional framework (see below).

The primary sources of law within the EC are contained within its treaties. The principal treaty is the Treaty of Rome 1957, which was the document that the original six nations signed on joining the EEC. The document covering membership of the European Coal and Steel Community was the Treaty of Paris, and another treaty signed in Rome instituted the European Atomic Energy Community. Since then a number of additional primary sources of law have been created; this is in addition to the treaties which have been introduced whenever new members join the community.

EXPANSION OF THE COMMUNITY

The first enlargement of the community took place in 1973 with the Accession Treaty, which was signed by Denmark, Ireland and the UK. After its return to democracy, Greece joined the European Community in 1981, followed by Spain and Portugal in 1986. More recently Austria, Sweden and Finland became members on 1 January 1995, expanding the community even further. Turkey, Malta and Cyprus have also applied for membership and it is likely that Malta and Cyprus will become members. Turkey’s position is, however, a little more problematic due to its lower level of economic development.

INTRODUCTION OF NEW TREATIES

Other additional treaties of importance include:

- the Merger Treaty 1965.

- the Single European Act 1986.

- the Treaty on European union, agreed in Maastricht on 11 December 1991 (which took effect on 1 November 1993).

The Merger Treaty

The Merger Treaty of 1965 was primarily responsible for establishing a single Council and a single Commission for all three communities. Previously, each community had its own institution. This later proved to be inconvenient and the Merger Treaty, which was implemented on 1 July 1967, combined the three institutions into one.

The Single European Act

The Single European Act was the first amendment to the EC Treaty. It came about as a result of pressure for greater union, and concern over increased competition from North America and the Far East. Its major amendments include:

- Changes in the powers of the Commission.

- Creation of a co-operation procedure, speeding up legislative procedure and giving enhanced legislative powers to the European Parliament.

- Co-operation in the field of foreign policy.

- Co-operation in economic and monetary policy.

- Common policy for the environment.

- Introduction of measures to ensure economic and social cohesion of the community.

- Harmonisation in the field of:

- Health

- Safety

- Consumer protection

- Academic, professional and vocational qualifications

- Public procurement

- VAT and Excise duties

- Frontier controls

- Lastly, it set 31 December 1992 as the target date for the completion of the internal market.

Treaty on European Union (Maastricht)

The Treaty on European Union is the most recent amendment to the EC Treaty. This Treaty creates a European union with three pillars including:

- Common foreign and security policy.

- Home affairs and immigration.

- Justice policy.

The Treaty on European Union (TEU) is responsible for the renaming of the European Economic Community as the European Union, thus reflecting the fact that the community is not just concerned with pulling together on an economic level but also intends to integrate on social and political issues. In addition, the TEU brings about important changes to the powers of the community’s institutions (see later chapters), and it sets out the procedure and timetable for creating economic and monetary union (EMU). The Treaty contains a number of opt-out provisions, and several member states have taken advantage of these. Denmark, Ireland and the UK have all opted-out of certain provisions; the UK, specifically, has opted-out from the third stage of the EMU programme.

The Treaty of Rome marked the beginning of the EC and it can also be broadly described as its constitution, since it contains the overall objectives of the community. However, this Treaty now has to be read in conjunction with the changes introduced by subsequent treaties, particularly the TEU.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF GENERAL PRINCIPLES IN EC LAW

The European Community and its legal system have no parallel either past or present, and as time progresses and new treaties are introduced the development of the EC engenders a sense of both excitement and uncertainty. There are two main sources of EC law:

namely, primary and secondary sources. Primary sources of EC law stem from the various treaties discussed above. Secondary legislation consists of regulations, directives and decisions. In addition, the EC has developed general principles which are used as a guide to help interpret EC law. These general provisions cannot, however, prevail over any provisions laid down in the treaties. Nevertheless, general principles have become an important tool to aid interpretation and challenges to EC law.

namely, primary and secondary sources. Primary sources of EC law stem from the various treaties discussed above. Secondary legislation consists of regulations, directives and decisions. In addition, the EC has developed general principles which are used as a guide to help interpret EC law. These general provisions cannot, however, prevail over any provisions laid down in the treaties. Nevertheless, general principles have become an important tool to aid interpretation and challenges to EC law.

The general principles include:

- Fundamental rights.

- Proportionality.

- Equality.

- Legal certainty.

- Procedural rights.

Fundamental Rights

Respect for fundamental rights now forms an integral part of the general principles of law. This concept of respecting fundamental human rights is closely associated with natural justice. The classes of rights that the European Court of Justice have recognised as fundamental include respect for property rights (Nold v. Commission 4/73 [1974] ECR 491), religious rights (Prais v. Council 130/75 [1976] ECR 1589) and the right to family life (Demirel v. Stadt schwabisch Gmund 12/86 [1987] ECR 3719).

Proportionality

This is based on the principle that the ‘punishment must fit the crime’. The key question posed is whether the same aim could have been achieved by a method which does not infringe EC law? If there are alternative routes available and these are not adopted, then the method used is disproportionate. If a result can be achieved by a route that does not infringe EC law, that route should be used, thereby making the measure proportionate.

Equality

This principle expects similar cases to be treated in the same way and if, for some reason, they are treated differently, there has to be an objective justification for the different treatment. The concept of equality is further recognised under treaty provisions. For instance, Article 7 of the EC Treaty prohibits discrimination on the grounds of nationality; Article 119 prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex, demanding equal pay for men and women for equal work; and, finally, Article 40(3) prohibits discrimination between producers and consumers within the community.

Legal Certainty

Legal certainty forms an important aspect of most legal systems. It operates with various subconcepts such as non-retroactivity and legitimate expectations.

Legitimate expectation is a concept derived from German law and basically it ensures that all matters relied on in good faith are respected. Therefore, Community measures must not violate the expectations of the parties concerned, unless such violation is necessary in order to protect the public interest. Thus, if the parties in question firmly believe a particular course of action will be followed and it is reasonable for them to do so, they may then rely on that expectation.

FIGURE 1 THE STRUCTURE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

The non-retroactivity principle applies to secondary legislation: namely, regulations, directives and decisions. It prevents a measure from taking effect before its publication. Retroactivity is allowed only if it is necessary to achieve particular objectives and provided individuals’ legitimate expectations are respected.

Procedural Rights

Certain procedural rights have been recognised by the EC which include:

- Right to a hearing (Natural Justice)—a concept adopted from English administrative law.

- The duty to give reasons (that is, reasons upon which the decision was made).

- The right to due process.

2

The Institutions of the

European Community

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION

This institution has been defined in many ways—as the executive of the Community and as its driving force and initiator. The Commission consists of 20 members who are appointed by the governments of the member states. France, Italy, Germany, Spain and the UK have two Commissioners and the other states have one each. The aforementioned five nations each have an additional Commissioner because they are the largest states within the EC in terms of population.

This factor also has significance when considering the number of seats allocated to each state in the European Parliament and weighted voting in the Council.

This factor also has significance when considering the number of seats allocated to each state in the European Parliament and weighted voting in the Council.

Although appointed by agreement of the governments of the member states, the Commissioners are under an obligation neither to seek nor take instructions from any government or from any other body. This is an obligation imposed by Article 10 of the Merger Treaty. Article 11 of the Merger Treaty states that Commissioners must be appointed by ‘common accord’. Each appointment must be agreed by all member states and, since the Treaty on European Union came into being, the European Parliament can now veto the appointment of Commissioners. A vital requirement of any Commissioner’s function is that

they must be prepared to act in the overall interests of the EC and be independent of their respective national governments. Partisan and national loyalties must, therefore, be subordinate to their function within the Commission.

Individual Commissioners can be required to resign on grounds of serious misconduct or the inability to perform properly his or her duties, and the entire Commission may be dismissed by the European Parliament on a two thirds majority provided that a minimum number of its members are present.

The duties of the Commission are numerous and varied. Each Commissioner also has responsibility for at least one subject area (a portfolio). Each subject constitutes an area of activity headed by one of 23 Director-Generals within the Community’s bureaucracy, which can loosely be compared to our civil service. The Commission in this respect may therefore be compared to its equivalent institution in Br...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- 1. THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT AND PRIMARY SOURCES OF EUROPEAN UNION LAW

- 2. THE INSTITUTIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

- 3. THE COUNCIL

- 4. THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

- 5. THE EUROPEAN COURT OF JUSTICE AND THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE

- 6. SECONDARY LEGISLATION

- 7. THE SUPREMACY OF EC LAW

- 8. EUROPEAN COMMUNITY LAW IN ACTION

- 9. FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS

- TABLE OF STATUTES

- TABLE OF CASES