- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 1978. In the case of slow learners the first and most critical thing to do is to recognise that children are individuals and then to break the circle of failure they expect to tread. All the ideas and suggestions in this book, therefore, are governed by this belief. Each chapter is self-contained in so far as it can be read by itself and as a reference if a teacher or parent is meeting a particular difficulty in that field. Some chapters are pertinent to both primary and secondary school teachers, some, more to one age group than another, but all are related. The appendices are itemised separately so that their information may be used on its own. All the materials, ideas and suggestions, are from practising teachers and have been, or are being at the present time, used in schools.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Slow Learners by Diane Griffin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

THE NEEDS OF SLOW LEARNERS AS INDIVIDUALS

What is a slow learner?

Any book about slow learners must first try to define what a ‘slow learner’ is. The term ‘slow learner’ is generally regarded in a derogatory sense. Slow to learn what? In most cases the slow learner is so described because he fails to learn at the same rate as the majority of other pupils learn. He fails to learn, in an academic setting, what teachers feel he should learn. He is not slow at covering up a depressing home situation, or a particular learning difficulty, or the fact that his father is in prison. It is usually the reverse. He is very adept at covering up things of that nature.

Most teachers have had experience of slow learners at some time or another, and the new teachers are warned before they begin of the terrible problems that they will encounter with ‘slow learners’, or ‘Newsom Children’ or ‘Rosla Children’ or the ‘Backward Class’. This group of pupils, rarely seen as individuals, but lumped together in uncomplimentary terms as though some particular breed, are of course individuals. They are individuals who need even greater care and understanding than most. They should not be thought of or treated as third-class citizens to be tolerated and occupied, or even worse, ‘to be held in check and tightly controlled’.

The only thing they have in common is that by the time they reach secondary school they are all seen, by themselves, by their parents, by teachers and by other students as failures. The cause of their failure may be due to many reasons; an apparent or non-apparent physical handicap; a congenital defect; a disruptive and stressful home situation; material or emotional deprivation; a serious conflict with school or a teacher early in their school career; or intellectual lethargy. Whatever the cause, the slow learner has become accustomed to failure. Indeed he expects to fail.

Breaking the circle of failure

The expectation of failure is a vicious circle. Most slow learners, because they see themselves as failures, don’t really try hard. After all, whatever they do will be of no use, so why bother to do anything? The most important problem to solve when dealing with slow learners is to find a way to overcome their negative attitude to themselves and their feelings of lack of self-worth. The only way to do this is to foster individual relationships and to cater for the needs of each student as an individual: to know and to care—to recognise the problems—to encourage and persuade—to find a way towards a solution, and mutually rejoice at success.

What are the objectives? Where do we start?

The most we can hope to do is to help every individual to realise all his potentialities and become completely himself. (Aldous Huxley)

Before the teacher can begin to do anything to help the slow learners he must analyse their needs in an honest and realistic way —the needs that they have now, and those they will have in the future. Is it desirable, or necessary, for them to cover the same, or a watered-down version of the syllabus of the rest of the school? Will an end-result of a grade 5 C.S.E. be worth the effort? Will that kind of learning give them the ability to work at a problem and be able to solve it? The future is uncertain for all of us. Attitudes and demand are changing rapidly. But we do know that whatever is in store, the slow learners, in common with everyone else, will have to think. They will have to understand, make judgments, make decisions. They will have to feel, cope with emotions, upheavals, love and hate. They will need a positive attitude to life. To accept these as their needs, means that we, as teachers, must be prepared to direct our teaching towards the needs of the individual pupil and the development of that pupil. “Help them to feel confident and they will become socially competent; help them to think and they will solve their problems; help them to understand and they will understand themselves.” (Kenneth J.Weber)

Motivation—a prime factor

One thing is certain. By the time the slow learner reaches secondary school, a prime factor in his learning will be ‘motivation’. The desire to learn to read or paint or sing or do experiments in science will depend very much on the pupil’s own wish to take part in an activity. This, in turn, wll depend on the degree of success he expects to achieve, and the relevance to his own life that he feels the task offers. Very often the only way of reversing the pattern of reluctance to attempt a task depends on the strength of a relationship. It is not possible for a teacher to go into a class and immediately establish a meaningful relationship. It is possible, however, to approach a class of slow learners without fear or prejudice. Some ‘bottom stream’ classes wait for the new teacher to indicate that he knows they are the ‘thickies’. They accept this as true themselves, so why shouldn’t the new teacher? It should not be surprising, therefore, if they act ‘thick’ either by passively showing no interest in anything or by behaving disruptively and noisily. Quite often they work hard to bring about what they feel is the normal state, the state of conflict!

What does a new teacher do when confronted with this situation? The only viable thing to do is to be honest, to say, ‘Look, I believe you are all individuals, all different and all important. I want to get to know you, to find out what you are good at and to learn with you.’ It is my experience that most pupils instinctively recognise a sincere teacher and do respond to that kind of approach.

Mutual trust

It is important, of course, for the teacher to then start proving that he genuinely cares and to begin to build an atmosphere of mutual trust. How can this be done?

- By being well organised, i.e., having planned and prepared a variety of suitable material whereby each pupil is certain of success.

- By showing a willingness to take the pupil’s own interests as a starting point.

- By acknowledging the cultural difference as present and important and welcoming whatever the pupil contributes.

- By taking careful notice of what the pupil produces and clearly indicating in some way, such as a fairly long written comment, or verbal discussion, that you have read and appreciated it. (B+, or Well done, or Improved, is meaningless.)

These are first steps in building up a relationship and are vital. The desire to please each other offers a strong motivational force. There must be empathy, trust and acceptance.

The role of the teacher

‘There is no such thing as competence without love.’ (John Dewey)

The role of the teacher is important. It would be wrong to read for ‘good relationships’, ‘putting up with anything’. The teacher who tries to fulfil every pupil’s whim, to sublimate his own desire completely, is setting up an unreal situation and preventing the development of the pupil. The relationship needs to be of the kind where neither the teacher nor the student has pre-eminence. It should be one where the roles are interchangeable, and each recognises the special position and value of the other. The teacher needs to act as a guide to the pupil, to help to direct his learning. This cannot be done successfully unless the teacher knows the pupils well and learns with them. In practice, this kind of role is much more difficult, if not impossible, if one teacher sees a pupil for specialist subjects and another teacher sees him for pastoral purposes. The two roles cannot be separated. Therefore, if a teacher is to establish a successful relationship he must spend a considerable amount of time with the same group of pupils. This can be done, as can be seen by looking at what happens in many infant and primary schools. Secondary schools, too, need to rethink their priorities.

If a relationship gets off to a reasonable start it can often be helped by getting out of the school environment. A swimming trip, a picnic, helping with a new garden, babysitting, a shared cinema visit, community work. All these activities reinforce the positive element of trust. They not only have the value of adding something to the relationship between pupil and teacher, but show to a peer group that the student can be trusted and successful and his company enjoyed; that teacher and pupil are learning together. It starts to make a chink in the circle of perpetual failure.

The role of the peer group

The role of the peer group also plays an important part in motivation. Usually a group has formed because of something they have in common. In the case of slow learners the thing they have in common is ‘failure’; academic failure, emotional failure, physical failure, quite often judged by others a failure to reach the same material standard. They cover up by being introverted, withdrawn; no one speaks much to them. Conversely they can be noisy and difficult; everyone is afraid of them; they are on the defensive and everyone is condescending towards them. They will tell you, ‘We’re the dummies. We’re the thickies.’ They reinforce in each other their own belief in their uselessness but a success or trust situation can counteract these feelings. They unconsciously think that if one of their number is trusted, is successful, then maybe they could be too.

The role of the parent

The parent of the slow learner can be placed into many categories: the over-protective, the over-permissive, the wilfully neglectful, or, in the case of handicapped pupils, bewildered, hurt and overworked. Some parents find it impossible to understand why their child is ‘slow’. Public attitudes are quickly conveyed to the parents of slow learners or ‘bottom stream pupils’. Tolerance and acceptance of people’s difficulties is still seriously lacking even with today’s more liberal attitudes. Parents are greatly affected by public attitudes and subconsciously reflect these feelings and project them towards their own child. The Plowden Report produces evidence to show that as much as 24 per cent variation in a child’s performance can be accredited to the amount of help or lack of help that parents contribute. In a summary of an experiment the Plowden Report shows that when attempts were made to influence parental behaviour, improvement was most marked among the least able children. It follows from this then, that every effort should be made to involve parents in any way possible.

It should be remembered and accepted that many parents of slow learners are themselves the victims of unhappy school experiences. If not actually anti-teacher, then they are ‘afraid of teacher’. It is highly likely that they bear a reluctance to come to school, especially on formal Parents’ Evenings, where they might be afraid of being an object of shame, or they might be just nervous. To counteract this, it is necessary for the teacher to go to the home, or the club or the pub. An anxious mother is far more likely to feel secure in her own home, thereby responding more openly to genuine discussion than she would if perched on the edge of a hard chair in the school library. Father will relax far more in his local over a pint of beer and therefore will be far more likely to commit himself to some kind of constructive help towards his child. Once the initial barriers have been broken down then it becomes easier to draw the parents into the school occasionally. When pupils are about to be transferred to a new school the opportunity arises to put into practice some kind of plan to set up good teacher/parent relationships. Some of the following could provide a basis:

- Getting to know the school—a preliminary visit and opportunity for the parent to meet the form teacher or tutor who will spend the greatest amount of time with a particular pupil.

- Open school—that is the kind of atmosphere whereby parents are always welcomed and feel able to drop in.

- Home visits for parents who are reluctant to come near the school.

- A newsletter or some other means whereby parents can be kept in touch with what is happening in the school. It is important that a newsletter for this purpose should be informal, friendly and easy to understand.

- Meaningful reports avoiding at all costs the Fair, Tried hard, B+, technique.

- Give simple advice to parents wanting to help their children, e.g. ‘Try to hear your child read for about ten minutes each day.’ ‘Praise him frequently for what he does accomplish’. ‘Give him somewhere special to keep his work’.

If we are to get the best from the pupil then we must aim to break down the reserve and build up informal and friendly relationships not only with him, but with his parents.

The classroom environment

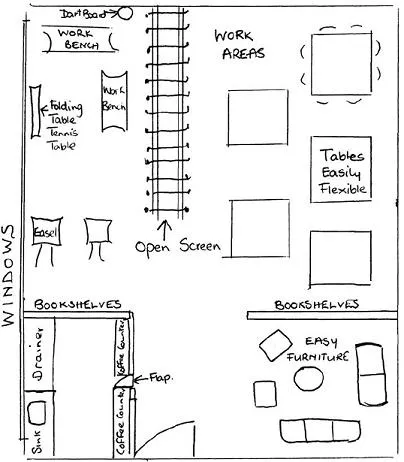

The environment plays an important part in bringing about a change of attitude in slow learners towards school. For most, the traditional classroom—rows of desks, hard chairs, blackboard and chalk, and an imposing teacher’s desk—holds few pleasant memories and sets the scene for rigidity and inflexibility. Ideally, a complete change of scenery is desirable and if the opportunity allows, using what always proves to be the not inconsiderable talents of the students themselves to bring about this change, it is wholly beneficial. The room could be decorated; old furniture bought and renovated and a small coffee unit built in one corner, a work area in another, a leisure-cum-reading area, a practical area (see diagram).

This, if done imaginatively, can be accomplished for very little cost and provides the basis for giving a sense of identity. It is surprising what local firms will donate if approached personally and it is comparatively easy to persuade people to part with old upholstered suites and chairs. Secondhand carpets can be obtained for about £10 and are well worth the money for the extra feeling of comfort and pleasantness they can bring to a room. If the ideal cannot be achieved because of the inflexible structure of the school, then at least the existing furniture moved around will help break away from the traditional rows. Everything possible should be done to individualise the room and provide within it clearly defined areas.

It is important to have within a room as much display space as possible in order to show the students’ own work and to hold frequently changed displays of things which interest them. Initially, it may be necessary for the teacher to mount these displays but it has certainly been my experience that in time the pupils themselves ask to take this job over and they get a lot of satisfaction out of so doing.

Diagram

Possible layout of classroom This helps to bring about a change of attitude and a sense of belonging. Using the goodwill of local firms and the ‘manpower’ of willing students and parents a traditional room in an old school was transformed into this for less than £35. There was never any problem over vandalism.

Devising some system whereby pupils can make coffee and sit and drink it in reasonably pleasant surroundings is well worthwhile. It not only relaxes the atmosphere but provides a stimulus for talk. I believe that it is inexcusable to turn adolescent slow learners out into a playground during breaks and lunch times. These are the times when they feel most insec...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Needs of Slow Learners As Individuals

- Chapter 2: Diagnosis

- Chapter 3: Reading

- Chapter 4: Learning Difficulties In Mathematics

- Chapter 5: Social Studies

- Chapter 6: Health and Sex Education

- Chapter 7: Drama and Photography As Means of Communication

- Chapter 8: Resources and Materials

- Chapter 9: School Organisation and Slow Learners

- Chapter 10: Help from Social Agencies

- Appendix I: Useful Mathematical Materials for Slow Learners

- Appendix II: Example of C.S.E. Mathematics Syllabus

- Appendix III: A C.S.E. Mode III Syllabus for Community Studies (Parenthood)

- Appendix IV: Severely Remedial Children’s Creative Writing

- Appendix V: British Publishers’ Addresses

- Appendix VI: List of Schools Council Research and Development Projects for Use With Rosla Children

- Appendix VII: American Books and Materials for and About Slow Learners

- Bibliography