Industrial Biomimetics

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Industrial Biomimetics

About this book

Biomimetics is an innovative paradigm shift based on biodiversity for sustainability. Biodiversity is not only the result of evolutionary adaption but also the optimized solution of an epic combinatorial chemistry for sustainability, because the diversity has been acquired by biological processes and technology, including production processes, operating principles, and control systems, all of which differ from human technology. In the recent decades, biomimetics has gained a great deal of industrial interest because of its unique solutions for engineering problems.

In this book, researchers have contributed cutting-edge results from the viewpoint of two types of industrial applications of biomimetics. The first type starts with engineering tasks to solve an engineering problem using biomimetics, while the other starts with the knowledge of biology and its application to engineering fields. This book discusses both approaches. Edited by Profs. Masatsugu Shimomura and Akihiro Miyauchi, two prominent nanotechnology researchers, this book will appeal to advanced undergraduate- and graduate-level students of biology, chemistry, physics, and engineering and to researchers working in the areas of mechanics, optical devices, glue materials, sensor devices, and SEM observation of living matter.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

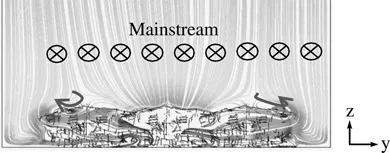

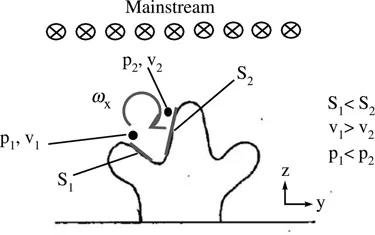

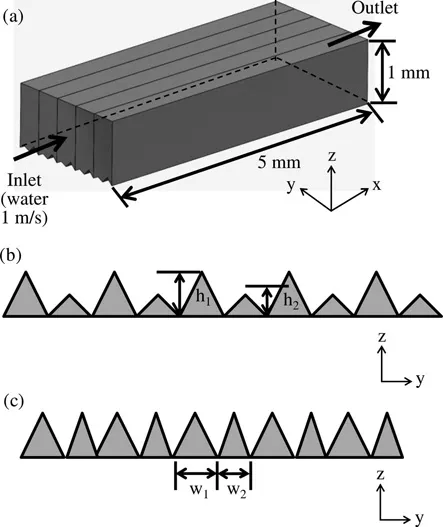

3D Modeling of Shark Skin and Prototype Diffuser for Fluid Control

[email protected]

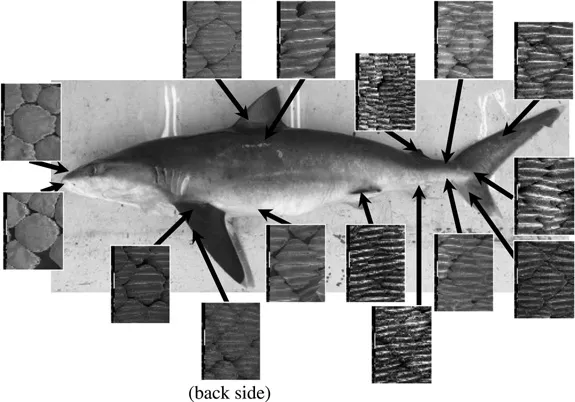

1.1 Analysis of Shark Skin

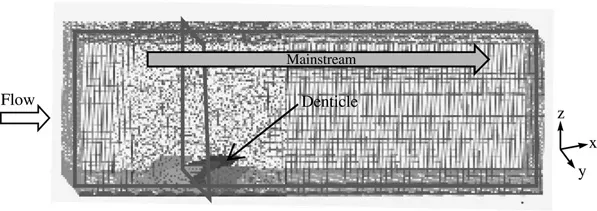

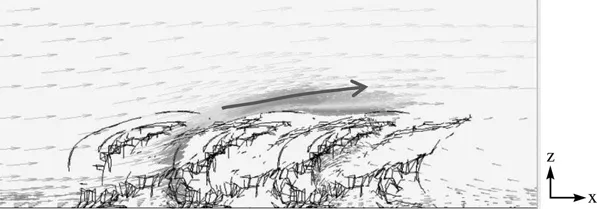

1.2 Biomimetic Design of Shark Skin

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 3D Modeling of Shark Skin and Prototype Diffuser for Fluid Control

- Chapter 2 Friction Control Surfaces in Nature: Analysis of Firebrat Scales

- Chapter 3 Biomechanics and Biomimetics in Flying and Swimming

- Chapter 4 Shape-Tunable Wrinkles Can Switch Frictional Properties

- Chapter 5 Self-Lubricating Gels: SLUGs

- Chapter 6 Bioinspired Materials for Thermal Management Applications

- Chapter 7 Strange Wing Folding in a Rove Beetle

- Chapter 8 Biotemplating Process for Electromagnetic Materials

- Chapter 9 Application of Structural Color

- Chapter 10 Moth Eye–Type Antireflection Films

- Chapter 11 Transparent Superhydrophobic Film Created through Biomimetics of Lotus Leaf and Moth Eye Structures

- Chapter 12 Adhesion under Wet Conditions Inspired by Marine Sessile Organisms

- Chapter 13 Functional Analysis of the Mechanical Design of the Cricket’s Wind Receptor Hair

- Chapter 14 Echolocation of Bats and Dolphins and Its Application

- Chapter 15 The “NanoSuit®” Preserves Wet/Living Organisms for Observation in High Resolution under a Scanning Electron Microscope

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app