- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Speaking of Dance: Twelve Contemporary Choreographers onTheir Craft delves into the choreographic processes of some of America's most engaging and revolutionary dancemakers. Based on personal interviews, the book's narratives reveal the methods and quests of, among others, Merce Cunningham, Meredith Monk, Bill T. Jones, Trisha Brown, and Mark Morris. Morgenroth shows how the ideas, craft, and passion that go into their work have led these choreographers to disrupt known forms and expectations. The history of dance in the making is revealed through the stories of these intelligent, articulate, and witty dance masters.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Speaking of Dance by Joyce Morgenroth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Merce Cunningham (b. 1919)

Merce Cunningham grew up in Centralia, Washington, where he studied dance with Maude Barrett. From her he learned tap dance and soft shoe, exhibition ballroom, and ethnic styles and had many opportunities to perform. After a year at George Washington University, he attended the Cornish School in Seattle, where he studied dance and theater and met John Cage, who was to be his lifelong collaborator. Cunningham went to New York in 1939 and joined Martha Graham’s dance company as a soloist. In 1945 he left Graham’s company, focused on choreographing, and in 1953 formed the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cunningham developed a dance technique that serves his choreography. Based on an upright posture with a flexible spine that can curve, arch, and twist, his technique emphasizes articulation, quickness, and the ability to change directions at any moment. His Westbeth Studio in New York’s West Village continues to be a prominent center for dance training.

Merce Cunningham has been a prolific choreographer for sixty years and has been arguably the most influential choreographer of the twentieth century (see the Historical Background section). As he modestly puts it, “Dance has been what’s interested me all my life.” He believes that movement itself is complete and needs no overlay of emotion or intention. Chance operations, the means by which decisions are made via a randomized method, have served Cunningham’s purposes, allowing him to establish the order of phrases, the choice of dancers, timings, and location in space without being limited by his own movement habits or dependent on dramatic narrative. Cunningham has collaborated with contemporary musicians and artists including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. He has also made dances for film and video that take advantage of the camera’s different spatial perspective. In the last decade he has used the DanceForms (formerly LifeForms) program as a way to devise new movement possibilities on the computer.

Merce Cunningham has received high honors from France, Italy, Sweden, England, and Spain. In America he was given the MacArthur “Genius” Award, the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, New York Dance and Performance (Bessie) Awards, John Simon Guggenheim Fellowships, the National Medal of Arts, the Dance/USA National Honor, the Samuel H. Scripps Award for Lifetime Contribution to Dance, and Kennedy Center Honors, among others, and was inducted into the National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame. He has been granted honorary doctorates from Wesleyan University and the University of Illinois.

* * *

Merce Cunningham at the computer (photo Edward Santalone)

Merce Cunningham

Way back a long, long time ago I began to work with some dancers. It was the 1950s. I didn’t have any money and I certainly couldn’t pay anybody since I was barely surviving myself, so I tried to think of what I could give the dancers in return for their labors. I thought, well, maybe teaching class. So I rented a studio for about a dollar an hour where we could get together and I would give class. The class was used as a laboratory, as a way to try out movement material. It also helped develop a common vocabulary. I had tried working with dancers from other techniques or styles, both ballet and the existing styles of modern dance, and I could see it didn’t work. Then when we had enough time to rehearse, we would work on a dance. That’s how it started and then it just kept up.

There were six dancers in the beginning, including myself, and we worked closely together. There are more of them now, which makes it more complicated to be with each one of them. I try to still see them as individual dancers as much as I can. Nonetheless, I think the relationship between me and my dancers is more formal these days than in the past. I don’t know if the dancers are scared exactly—of me or the work. I know there’s always a risk on both sides when beginning something new, particularly because of the way we work in my company. But the work goes on between us.

These days I give the company class and so do my assistant Robert Swinston and others. That’s very much a part of our routine. When we’re on tour of course it’s hard to get up the morning after a show and do a class, but it’s always better if you do. I remember once Ulysses Dove, who was with our company and then later with the Ailey Company, complained about class on tour. I said, “But Ulysses, isn’t it better with it than without?” and he admitted, “You’re right.” I know our dancers want class. It’s a way of establishing your balance again.

I don’t like teaching because it’s so repetitive, especially the beginning of class, which is always more or less the same and has to be carefully done. It’s tedious. But I know it’s necessary for dancers to keep working on technique. At least in our work it is, because the work is difficult. It’s not enough to study a technique until you arrive at the point where you’re skilled. I think many people stop there and think that’s adequate. I always thought of that as the beginning; you have to go further and, as John Cage once said, make a few mistakes, so it’s human and not simply rote.

My work always comes from the same source—from movement. It doesn’t necessarily come from an outside idea, though the source can be something small or large that I’ve seen, often birds or other animals. The seeing then can provoke the imagining. For example, I might see a person walking in a way that I decide is odd. I don’t want to know what caused it but how it was done. So then I often take it back to the studio and try to remember it physically, try to find out in my own body what it was. It’s usually something that is outside of my own physical experience. It may be simply that somebody has a bad leg (which, unfortunately, is in my physical experience) or it may be a shape or rhythm that strikes me about the movement. I think anything can feed you, depending on the way you look at it or listen to it.

What really made me think about space and begin to think about ways to use it was Einstein’s statement that there are no fixed points in space. Everything in the universe is moving all the time. His statement gave rise to the idea that in choreographing a dance you didn’t have to have some sort of central point being more important than any other. You could have something happen at any point on the stage and it would be just as important as something happening somewhere else. You could have several groups in the space at the same time. I thought immediately that it’s a remarkable way to think about the stage. So I applied it.

The solution to a practical theater problem sometimes has led me in new directions. In 1964 the first “Event” happened because the company was performing in a space where there wasn’t a stage. Instead of our showing complete dances, I decided to put together a piece using excerpts from the repertory that the company was doing on that tour. We called it Museum Event #1. And we discovered that this worked well and was a way to use unconventional spaces—whether other museums, as we did later in that tour, or the Piazza San Marco in Venice, or Grand Central Station.

My process has changed over the years. I’d say it has been enhanced. When I began working with John Cage in the 1940s we soon separated the music and the dance. He would compose a piece of music and I would choreograph a dance of the same duration, but we didn’t have to know anything more about what the other was doing. That independence immediately provoked a whole different way of working physically. The dancers had to learn how to be consistent in the timing of their movement so that no matter what they heard in performance, the dance would take the same amount of time to perform. I began to use a stopwatch in rehearsal. This way of working was difficult but, at the same time, it was unbelievably interesting and has remained that way. The dance was freed to have its own rhythms, as was the music. Steps could be organized independently of the sound. In one particular moment in one of those early pieces, even before we had completely separated the music and the dance, I did a strong movement and then John made a strong sound, but separately. That was a moment for me when I saw that if the two had been planned to happen together, it would have been conventional and unsurprising. But this way it was different. The independence allowed for a sense of freedom. The dancers weren’t dependent on the music. John didn’t want the music to dictate to the dance or the dance to dictate to the music, which was the situation that had existed before. The separation was his idea.

Then the use of chance operations opened out my way of working. The body tends to be habitual. The use of chance allowed us to find new ways to move and to put movements together that would not otherwise have been available to us. It revealed possibilities that were always there except that my mind hadn’t seen them. A chance system can be used to determine the sequence of phrases and where in space they will occur. It can determine the timing and rhythm of particular movements or which dancers will do a given phrase. I sometimes throw dice using the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes . Since there are sixty-four hexagrams in the I Ching, I throw eight-sided dice, which allows me to generate eight-times-eight decisions. If I use chance to come up with a sequence of movements, I might consider the outcome and think, “Well, is that possible?” Of course, even if I devise something by chance operations I then have to work it out by exploring movement physically—on myself or more often lately it may be on the dancers. We try it out and maybe it isn’t possible, but some other possibilities come up. In using chance operations the mind is enriched.

By the early 1970s I was beginning to work with video. I had never before had anything to do with a camera. With Charles Atlas, then with Elliot Caplan, the company made several dance films—or film dances—or whatever they want to call them. Originally I made these dances entirely for camera even though later I changed some of them into stage works. I saw immediately when I looked through the camera that there is a basic difference in the way the space is perceived. On the stage we see the space as wide to narrow. In the camera it’s the other way; we see narrow to wide. It’s a technical difference. And I found it stimulating. And, like everything else, difficult.

While we were making work for television I realized that when people are watching television, they can always turn the channel. If you simply repeat the movement, they’re going to see what’s on someplace else. But fortunately with the camera you have recourse to possibilities that are not available on the stage. You can do one repeat and then catch the movement from the other side, and so on. You can see things in such detail. And the technology! Even in my limited involvement, it has jumped.

With dance computers, the technology can take you even further. I have been working with the LifeForms program since the early nineties. Using LifeForms, if you put a computer-generated figure into one position and then into another, the program does the transition from one to the other. You can first make the phrases on the computer, then teach them to the dancers. The resulting movements may be more peculiar than a body would tend to do. That interests me. Before I meet with the dancers these days I start by making movement, which I may have worked out to some extent on the computer. Then I bring it to the dancers and work together with them within my capacity but also with their gifts. I show them first what the legs are doing. Then I add the torso and finally the arms, so they all know all the material. But then I can break it down into who does what, when they do it, and where. That’s when I begin to see what we have and change it if need be. The changes may be for practical reasons or because I now see other possibilities. I use the computer as a tool. Like chance or the camera or the other tools I’ve used, it can open my eye to other ways of seeing or of making dances. It’s not simply to do a trick. These are not tricks to me, but real things that are in life.

Possibilities came up through working with other artists, particularly Cage of course, but other composers as well, and certainly with visual artists. Even though we don’t work the same way, I have found their ideas so interesting. In the early years of our working, dancers generally didn’t know anything about the visual world. I remember one time the artist Bob Rauschenberg did some lighting for us at a summer school and the producers there thought he was crazy because he didn’t know anything about what lights could do. Then I told them to just let him do what he wants; I had to fight to get them to do that. And what he did was marvelous. The next summer he began to be known. Then they wanted him to do a poster!

Rauschenberg and I still sometimes work together. He made the stunning décor a couple of years ago for Interscape. Although he lives in Florida, he came to New York and looked at the dance when it was partially done. He wanted to know all the dancers’ names and had Polaroid pictures taken of each one. He took the photos back to Florida and made the costumes particularly for each of the dancers. What he did was beautiful. That kind of collaboration I enjoy very much.

At the beginning of each piece I usually have some idea about its length. After all, the composer needs to know. One of my recent pieces, I think it was BIPED , was forty-five minutes long because the commission stipulated that length. I thought, “Okay, that’s fine. We’ll deal with that length.”Often the composer will want to know something else as well. Cage always wanted to know what my structure was, if I had one. I often did have some sense of the time structure. Then he’d make a different one for the music. It’s not more detailed than that when we start, although the composer can always ask questions or come and look.

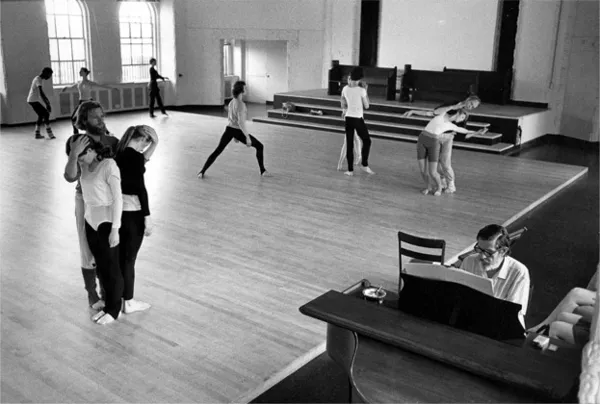

Rehearsal of Second Hand by Merce Cunningham, with John Cage at piano (photo James Klosty)

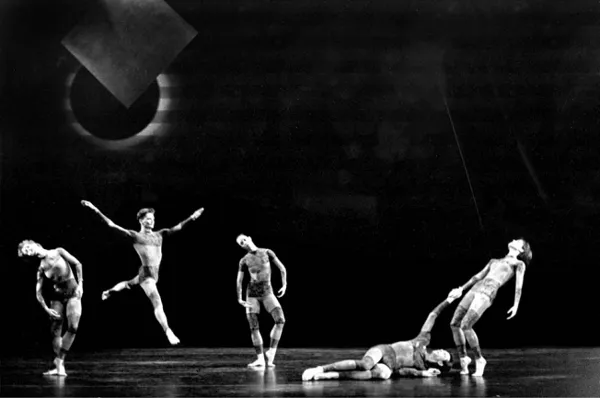

Field and Figures by Merce Cunningham (photo Tom Brazil)

Fortunately, dance has been what’s interested me all my life. So whether I am faced with incapacities or not, it still absorbs me. When years ago the press was so bitter against us, I remember once thinking I should read the reviews. I read some of that stuff and then just quit looking at it. And since then I never read it; I don’t care. Maybe their critiques are right in the sense that I’m not using these possible ideas very well. But it’s what interests me. That’s stronger than anything they could say or write. I don’t mean it was easy to ignore a negative response. It’s hard to present dances and see everybody turn away.

Sometimes, because of deadlines, we have to present a piece when, for me, it isn’t quite finished. I have limited choreographic time and I always know what the deadline is. But because of the complexity of the way I work—which continues to get more complex—it takes a long time. This is not so much because of the dancers, who are quite quick, but with my figuring it out. After we present it I continue working on it until I consider it finished. That point might occur a month or so after the opening. That’s fine. When I get to the end of a piece I’m usually relieved, in a way. Then we put it aside and don’t thin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Historical Background

- 1. Merce Cunningham

- 2. Anna Halprin

- 3. David Gordon

- 4. Trisha Brown

- 5. Lucinda Childs

- 6. Meredith Monk

- 7. Elizabeth Streb

- 8. Eiko Otake

- 9. Bill T. Jones

- 10. Ann Carlson

- 11. Mark Morris

- 12. John Jasperse

- Selected Bibliography

- Index