- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How do the Japanese and Okinawans remember Occupation? How is memory constructed and transmitted? Michael Molasky explores these questions through careful, sensitive readings of literature from mainland Japan and Okinawa. This book sheds light on difficult issues of war, violence, prostitution, colonialism and post-colonialism in the context of the Occupations of Japan and Okinawa.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa by Michael S. Molasky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Études ethniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Roads to no-man’s land

If you take off walking in a straight line on this island, you’ll end up facing the barbed-wire fence of a military base. If you don’t run into a barbed-wire fence, you’ll go right through until you reach the sea.

(Higashi Mineo 1972:67)

To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture.

(Frantz Fanon 1952:38)

The Okinawan historian, author, and playwright Ōshiro Masayasu begins his book Okinawa in the History of the Shōwa Era by discussing the symbolic role of National Highway 58 in modern Okinawan history.1 Although the road had existed for years, it was not designated a national highway until 15 May 1972, the day of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan after twenty-seven years of American military occupation. Ōshiro describes the road as viewed from his office window in Naha, at the southern end of Okinawa’s main island: Highway 58 runs north along the entire length of the island and traces an imaginary line across the water, passing through the islands of Amami Ōshima and Tanegashima before reaching Kagoshima City in Kyushu, roughly 450 miles to the north. During the occupation years, Highway 58 was commonly known as “Military Highway No. 1” and served as the island’s main artery for American military vehicles. Before the arrival of U.S. forces on the island of Okinawa in April 1945, portions of this route were used to transport Japanese troops. Thus the road known today as “National Highway 58” not only links post-reversion Okinawa to the rest of Japan but connects three phases of modern Okinawan history: the era of Japanese imperialism and war, the postwar American occupation, and the ensuing years since Okinawa regained Japanese prefectural status.

If Benedict Anderson is correct and the modern nation is indeed an imagined community, then what better testament to this idea than an invisible highway connecting a nation’s peripheral archipelago to its main islands?2 Yet it may be the actual discontinuity of Highway 58 that best represents Okinawa’s relationship with Japan, which has been fraught with ambivalence ever since Japan first “annexed” the Ryukyus in 1879. This ambivalent historical relationship, together with the sheer length and intensity of America’s occupation of the islands, has provided postwar Okinawan writers with a distinctive perspective on both foreign occupation and Japanese imperialism. The fictional narrative that may best exemplify this perspective is Ōshiro Tatsuhiro’s The Cocktail Party, which I discuss in this chapter together with Kojima Nobuo’s “The American School.”

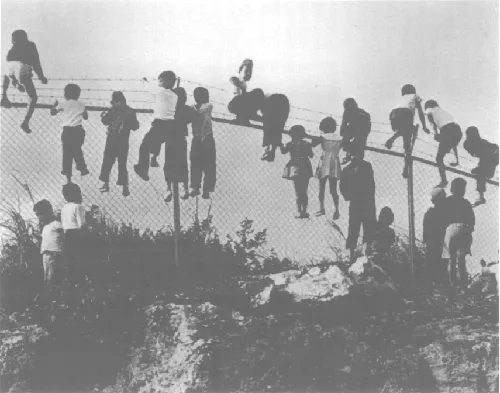

Okinawan children atop a fence surrounding an American military base. Early 1970s. (Photograph by Goya Eikōh, courtesy of Miyagi Etsujirō.)

Both “The American School” and The Cocktail Party have received the prestigious Akutagawa Prize for fiction. Yet I have selected these stories for discussion in this opening chapter not so much because they are enshrined within their respective literary canons but because they delineate several critical differences between Japanese and Okinawan occupation literature. At the same time, they feature many of the themes and narrative strategies commonly found in men’s stories from the two regions. For example, both works reveal how American control over social space disrupts and transforms the natural landscape; they represent the authority of the occupiers through their control over the realms of language and sex; they use “native women” to mediate relationships between the male occupiers and men of the occupied populace; and both works situate the postwar occupation against prewar Japanese militarism.

As I argue throughout this book, these are all common elements of men’s narratives on the occupation. I am especially interested in why male authors so often appropriate the female body to establish male victimhood. My readings are informed by the insights of feminist scholars Gayle Rubin, Luce Irigaray, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, whose writings reveal how men’s texts represent women as transactable commodities, as symbolic capital to be exchanged between men or to mediate relationships between men.3 I explore how, on the one hand, works such as The Cocktail Party condemn the sexual appropriation of local women by the foreign occupiers while these same texts appropriate the abstract figure of “woman” to construct the male protagonist’s sense of victimhood. These narratives construct victimhood by linking the female body to the nation, and those texts harboring a powerful allegorical impulse tend to represent the landscape as a gendered embodiment of the nation. My readings therefore focus on the interaction between the physical and social topography.

In the excerpt from Higashi Mineo’s story quoted in the epigraph, landscape is used to depict America’s occupation forces as intruders who have forced their way into, and rooted themselves within, native territory. The barbed-wire fence in Higashi’s story transects the natural landscape and separates the narrator (an Okinawan youth) from the nearby sea, an intimate part of the boy’s sense of home. As we will see, many stories from both Japan and Okinawa depict the occupier as an alien presence that has been internalized—either transplanted into the landscape or physically consumed by it—revealing how “the occupier within” impinges on the occupied subject’s freedom and identity.4 The image of an internalized occupier links landscape and body through their shared susceptibility to foreign penetration, and heavy sexual overtones are apparent here and in other paradigmatic tropes of penetration.

Such tropes are by no means limited to postwar Japan. Whether it be an 1880s Rider Haggard adventure depicting a British colonial hero piercing into the dark, virgin jungle or NBC News a century later denouncing “the rape of Kuwait,” these tropes of imperialist intervention project body onto landscape, which is endowed with gender (female) and subjected to sexual incursion by the advancing male. Colonial or military transgression of geographical territory is conjoined with sexual transgression of the individual body. These and related tropes thus rely on a logic that conflates individual body with national body and designates the transgressed body as female, emphasizing “her” subjugation and helplessness before the dominant male intruders.5 But as the organized rape camps of the Balkans remind us, and as the September 1995 abduction and rape of a twelve-year-old Okinawan girl by American servicemen further attests, rape by foreign soldiers cannot and should not be reduced to mere metaphor. On the contrary, the power of rape as a metaphor is contingent on our ability to imagine (or remember) the raw violence and terror of the act itself.

In men’s writing on the occupation of Japan and Okinawa, it is not only women who are rendered defenseless before the foreign troops. Male characters are also depicted as powerless, especially when they prove incapable of protecting the women around them from unruly occupation soldiers. These literary depictions of powerless men commonly rely on sexual metaphors of castration and impotence, metaphors that present the men as “feminized” and thereby equate men’s social powerlessness under foreign occupation with that of women under supposedly normal social conditions. Narratives that depict native men as sexually impotent often represent these same subjects as silenced, deprived of the power of speech. These narratives thus combine two forms of impotence—sexual and linguistic—to convey the thorough incapacitation of native men under American occupation. But as we will see in Kojima’s “The American School,” and later in Ōe Kenzaburō’s “Human Sheep” and Nosaka Akiyuki’s “American Hijiki,” to be silent does not necessarily imply an inability to speak.6 Silence can also constitute a form of resistance, particularly when it signals a refusal to speak the occupier’s language. One must therefore distinguish between silence representing the absence of subjectivity under foreign occupation and silence signaling an assertion of subjectivity through its deployment as a strategy of resistance. In both instances silence raises the question of control over the means of communication and draws attention to whether the occupied subject has a space from which to speak.7

Language, as both a symbol of power and as a medium through which it is exercised, has consistently been a key ideological issue in literary representations of occupation and colonialism. As sociolinguist John Edwards has argued, language is neither a necessary nor an exclusive marker of national (or ethnic) identity;8 but language does often appear at the center of struggles by subjugated peoples to reclaim or reconstruct their sense of identity.9 When Frantz Fanon observes that speaking another language entails taking on a new world, he refers specifically to the colonized African’s attempt to assume the world of the white colonizer, to don a white mask that will cover the African’s black skin. In many postcolonial literatures of Africa, South Asia, and the Caribbean, language confronts ideology as soon as the writer takes pen in hand, since one of the first questions facing the writer is which language to use—the language of the former colonizers, that of the local populace, or a hybrid of the two. Any choice signals an ideological position and defines the readership. Language and its ideological dimensions are therefore at issue not only within the story but at the surface level of the text.10

Unlike bilingual or multilingual writers from Europe’s former colonies, Japanese and Okinawan writers lack the option of writing in a European language because America’s occupation of the Japanese archipelago failed to foster a class of bilingual subjects. There emerged no distinct pidgin or Creole from which these writers might forge a new literary language to represent the experience of foreign occupation.11 What writers from Japan and Okinawa do have at their disposal is a flexible orthography capable of denoting difference on a tangible, visible plane: the katakana syllabary (rather than its counterpart, hiragana) is often employed to denote foreignness, and for readers sensitive to both the linguistic and social terrain, orthographic signs can point to real-world signs, joining the textual landscape with the natural landscape to highlight America’s pervasive influence on the occupied region. Japanese orthography also offers the writer several options in glossing individual words in the text, and the discriminating use of orthographic glosses can itself constitute a political position.12 Strategic deployment of orthographic combinations thereby enables Japanese and Okinawan writers to register both domination and difference at the very surface of the text. Orthographic choices also serve to highlight forms of linguistic hybridity and code-switching in Japanese narratives, and the attentive reader will be alert to both the aesthetic and the political implications of a text’s orthographic contours.13

Kojima Nobuo’s “The American School” and Ōshiro Tatsuhiro’s The Cocktail Party devote special attention to the relationship between language and identity under American occupation. The main characters in these two stories are teachers or students of a foreign language. In “The American School,” a Japanese group of English teachers with sharply divergent linguistic aptitudes and attitudes struggle with the English language, a language that represents opportunity while at the same time mediating their subjugation to America during the early postwar years. The three central characters in The Cocktail Party—an Okinawan, Japanese, and Chinese—join a Chinese language circle at the invitation of an American. The Chinese circle holds forth the promise of neutral linguistic territory for the four men in occupied Okinawa, yet as the Okinawan protagonist eventually discovers, there is no escaping their memories of the past war or the reality of the current occupation.

Both Kojima and Ōshiro had first-hand experience working in a foreign language during the war and occupation. Kojima was born in Gifu Prefecture and graduated from Tokyo Imperial University in 1941 with a degree in English literature. During World War II he was stationed in China and worked as a linguistic decoder and translator.14 After returning to Japan he taught English at a high school and later at Meiji University before establishing himself as a writer. Ōshiro spent his youth in Japanese-occupied China and later worked as a translator for the American occupiers of Okinawa. Both authors’ personal experience clearly informs their respective stories, but neither narrative should be construed as a “shishōsetsu,” for these stories are neither fiction posing as autobiography nor are they autobiography posing as thinly-veiled works of fiction.15

Language, landscape, and gender in “The American School”

Kojima Nobuo’s “The American School” takes place on the outskirts of Tokyo one day in the late 1940s. The story opens with a group of Japanese teachers waiting to embark on a six-kilometer walk to an American school, where they are scheduled to observe classes. The excursion has been arranged at great trouble by Japanese education officials, presumably for the English teachers to bolster their skills through exposure to an authentic English-speaking environment. One might also assume, in view of the spirit of the occupation, that a lesson in American democracy was in the offing.

Four of the story’s Japanese characters are presented by name: three of the English teachers—Yamada, Isa, and Michiko—and although he is featured less prominently, Shibamoto, the representative from the Office of Education. Only two of the Americans are named in the story: Mr. Williams, the principal of the American school, and Miss Emily, a teacher whose beauty purportedly rivals that of an American movie star (209; 132).16 Significantly, both the Japanese and American women are referred to by first name whereas the male characters are all referred to by surname. Naming is one technique for constructing and marking a character’s identity, and by assigning female characters with only first names, the women are rendered as subordinate to their male counterparts and as more “familiar” (which must be understood to be replete with sexual overtones).17 Women in this text function as symbolic capital exchanged between men, and both Michiko and Emily are evocative of the prostitute: Michiko because she circulates back and forth between groups of American and Japanese men, receiving and distributing commodities; and Emily due to her erotic encounter with Isa behind locked doors. The division of characters along gender lines, however, is subsumed under the category of nationality in the story. The names of the two Americans—Mr. Williams and Miss Emily—are always followed by suffixes (Uiriamu-shi and Emirii-jō) that accord the Americans respect and a lofty distance from the Japanese teachers. The naming of characters in “The American School” thus aids the story’s construction of a hierarchy in which Americans are placed above Japanese regardless of gender, and where men are placed above women within each national category. That the categories of gender and nationality articulate within a hierarchy is itself testimony to the difficulty of theorizing identity without reference to relations of power. It also serves as a reminder that identity is multi-faceted and that these facets often conflict.

Of the three Japanese teachers, Yamada is a zealot who will speak English to anyone and who will stop at nothing in his effort to impress the occupation forces. Yamada’s zeal appears to outflank his actual proficiency in the language, although he is able to convey his thoughts in English without undue effort. Isa, on the contrary, is a shy but stubborn man whose fear of speaking English rivals Yamada’s desire to use the language at every turn. In his compulsion to avoid speaking English, Isa has, in the past, even feigned illness a full two days in advance of his scheduled encounter with the spoken language. “The American School” often pits Isa against Yamada, presenting Yamada as the dauntless opportunist and Isa as the recalcitrant subversive. Yet both characters are defined in part by their awkward relationship to the English language. Michiko, the only woman in the group, is distinguished by her natural command of English. Her chameleon-like ability to switch back and forth between Japanese and English makes Michiko a liminal character. Her attitude toward the English language is ambivalent: she shares Yamada’s enthusiasm for English while disdaining his motives; she sympathizes with Isa’s distrust of fluency in a foreign tongue but finds her own fluency exhilarating. Unable to fully embrace either position, Michiko moves back and forth between Yamada and Isa. Her fluency, combined with her status as a woman, situates her as a mediator between the two men and between the Japanese and Americans, a mediator who is ultimately incapable of belonging fully to either group.

Michiko’s liminality is announced in the text through the mixed orthography used to write her name: “Michi” is written in katakana while “ko” is written in kanji (Chinese characters). Since no kanji are used to write the first two syllables of her name, the reader is left to speculate about the many possibilities. One choice (though perhaps not the most common) would be to write “Michi” with the single character signifying “road.” Much of the story occurs on a road connecting the world of Japan (the prefectural office, where the story begins) with that of America (the school). This road does not in itself constitute a specific place; rather, it is depicted as a cultural no-man’s land. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa

- Routledge Studies In Asia’s Transformations

- Preface

- Introduction: Burned-Out Ruins and Barbed-Wire Fences

- 1: Roads to No-Man’s Land

- 2: A Base Town In the Literary Imagination

- 3: A Darker Shade of Difference

- 4: Female Floodwalls

- 5: Ambivalent Allegories

- 6: The Occupier Within

- Epilogue: Occupation Literature In the Post-Vietnam Era

- Notes

- Bibliography