- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Culture/Place/Health

About this book

Culture/Place/Health is the first exploration of cultural-geographical health research for a decade, drawing on contemporary research undertaken by geographers and other social scientists to explore the links between culture, place and health. It uses a wealth of examples from societies around the world to assert the place of culture in shaping relations between health and place. It contributes to an expanding of horizons at the intersection of the discipline of geography and the multidisciplinary domain of health concerns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Culture/Place/Health by Wilbert M. Gesler,Robin A. Kearns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

This book explores the links between culture, place and health from our vantage point as both cultural and health geographers. These three domains of socialscientific concern have independently, and in paired combinations, been of considerable interest to anthropologists, sociologists and geographers for some time. Recently, however, the so-called ‘cultural turn’ in medical geography has contributed to the transformation of this field into a new formulation as ‘health geography’. The net result is an increasing interest in the way cultural beliefs and practices structure the sites of health experience and health care provision. Such sites are, from the geographer’s viewpoint, best regarded as places, given the rich nuances of that term which direct attention to both identity and location (Eyles 1985).

Our efforts to draw together a focus on this tripartite set of themes is an extension of our earlier concerns with the processes of ‘putting health into place’ (Kearns and Gesler 1998). In that volume, we and our contributing essayists focused on difference in health outcomes and service opportunities, an established emphasis in medical geography dating from the challenges of political economy (Jones and Moon 1987; Eyles and Woods 1982). However, throughout the 1990s, emerging concerns centred on views of difference that went beyond issues of material well-being. We and colleagues were concerned with difference in places of health care as well as in the health experiences of groups defined by such markers as class, ‘race’, sexuality, or gender (or combinations of these identities) and how these differences might be made visible in research. The present book steps back from the earlier case study approach to provide a survey of key themes in the cultural geography of health and health care. Our goal is a book aimed at a senior undergraduate and beginning graduate audience that will provide an accessible survey containing comprehensive reference to current literature. We introduce our book by first considering the three domains we seek to link. The discussion introduces many of the key themes we pursue in detail later such as structure and agency, narratives, difference, therapeutic landscapes, and consumerism. The chapter concludes with a glimpse at the changes taking place in health geography and a brief overview of the chapters that follow.

Culture

In his provocative volume, Don Mitchell (2000) asserts that while a decade ago, Peter Jackson (1989) offered an agenda for cultural geography, culture is now the agenda in human geography. Much the same can be said for health geography. Medical geography’s experience of the so-called ‘cultural turn’ has been its reformulation and reorientation towards health (Kearns and Moon 2001). However, the precise agenda of health geography is far from clear, and cultural geographies of health are literally and figuratively ‘all over the place’. Our goal is to more closely link cultural treatments of health in geography to social, political and economic forces. Drawing on Mitchell (2000: 6), we see that in the fields of health and health care there are ‘arguments over real spaces, over landscapes, over the social relations that define places in which we and others live’. These arguments signal the fact that health is a contested term, and health care a contested terrain.

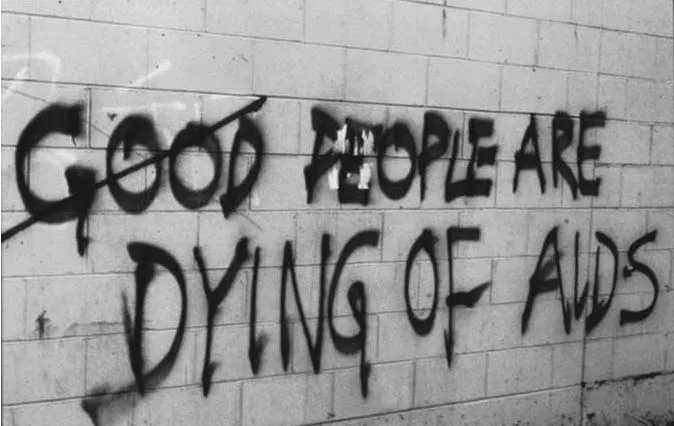

One does not need to look far for examples to substantiate this view that there is a cultural politics of health and health care. An enumeration of health concepts can produce a list of some twenty definitions ranging from the medical/easy-to- measure (‘absence of disease’) through to the ‘new age’/difficult-to-measure (‘wholeness’). In between, we can encounter variants that speak to economic as well as legalistic overtones (‘a purchasable product’, ‘a right’) (Lee 1982). The prevailing definition of health in any given place will shape what groups hold power over the processes involved. Contest over the ‘ownership’ of health leads to a power politics being mapped into the landscape of place through symbol, language or materiality. The fact that midwives cannot act independently in most hospitals, for instance, illustrates that the contest over women’s health results in health care facilities in turn becoming a contested terrain. As another example of the cultural politics of health, Figure 1.1 speaks to polarized views on the moral geography of AIDS. With a single line of spray-paint, a second practitioner of graffiti has called into question whether sympathy should be shown to AIDS patients. We say this speaks to a ‘moral geography’ because we believe that place matters. The graffiti in Figure 1.1 was photographed in the very mixed and impoverished downtown East Side neighbourhood of Vancouver, and we can speculate that such contested views would be less likely to appear within established gay areas such as Cawthra Park near St Michael’s Hospital and Casey House Hospice (see Chiotti and Joseph 1995) in Toronto. There, instead of outspoken graffiti we encounter a more respectful and enduring memorial to Canadians who have died of AIDS (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Graffiti, downtown East Side, Vancouver, 1994. Photo by Robin Kearns.

Talk of materiality and cultural politics might suggest we are attributing too much to bodies and the ‘bricks and mortar’ of health and health care. On the contrary, we agree with Mitchell (2000) that there is no such ‘thing’ as culture, but rather that culture is expressed through ‘the power-laden character and emplaced nature of social relations’ (Berg and Kearns 1997: 1). Such assertions signal our affiliation with the so-called ‘new’ cultural geography. While by its very prefix, this term is implicitly contrasted to an ‘older’ tradition, we strive for an inclusive view of work in cultural geography that contests the new/old binary construct. One reason for this view is that, especially beyond North America, many cultural geographers have always had a political edge to their work (Berg and Kearns 1997).

We are interested not only in how culture affects health, but how health affects culture. Health, illness and medicine have reflected, and contributed to, the fashioning of modern culture (Lawrence 1995). Bury (1998) identifies some key processes that are carrying their influence into a postmodern era. One of these processes is objectification, in which private activities or knowledge are made more public, in the sense of becoming increasingly open, revealed and accessible. An example of this is sexual health, in which advertising for drugs such as Viagra has publicized and medicalized a condition formerly discussed only behind the closed doors of a counselling room. For us, the relevance of this shift is that advertising literally takes place, adding to the landscape through billboards or contributing to everyday geographies through a range of media. A second process is rationalization, which Bury (1998) describes as the way in which modern medicalized life undermines self-identity through moving from the ‘citadel’ of the hospital or clinic into the community, thereby blurring the boundary between lay person and professional expert. For us the culture–place link is crucial in this observation. Efforts to calculate rationally the risks or the healthfulness of situations literally bring health home, and into other non-traditional healing places, thus fragmenting and re-placing voices of scientific authority. Through rationalization, patients have been (willingly or otherwise) transformed under recent expressions of capitalism into ‘consumers’: active purchasers of goods and services who have (often carefully circumscribed) rights of participation in policy debates. Our goal is to work, through an analysis of the linguistic and symbolic nature of ‘culture’, towards creating new understandings of ‘the consumer’, rather than simply adopting, adapting and testing explanations developed elsewhere.

Figure 1.2 AIDS memorial, Cawthra Park, Toronto. Photo by Robin Kearns.

Place

As geographers, we have as our foundational interest the idea of place. Most fundamentally, place is simply a portion of geographic space. Places can be thought of as ‘bounded settings in which social relations and identity are constituted’ (Duncan 2000: 582). These can be official geographical entities such as municipalities, or informally organized sites such as ‘home’ or ‘neighbourhood’. The idea of place, and the associated terms ‘sense of place’ and ‘placelessness’, were strategically deployed by humanistic geographers in the 1970s to distinguish their work and intent from ‘positivist’ geographers whose work dealt primarily with space.

Recent scholarship has moved away from the uncritical ‘humanistic’ phase of the 1970s and towards formulations that consider the ways in which place is forged through intersections of local and global factors, as well as individual agency and societal structures (Jackson and Penrose 1993). Doreen Massey (1997), for instance, strives for a progressive and global sense of place that moves on from earlier preoccupations with the (lost) ‘authenticity’ of rural and preindustrial places. The concept holds dangers, however. David Harvey (1989) suggests that interest in place can lead to a preoccupation with image through recourse to romantic myths of community. Similarly, from a gender perspective, Gillian Rose (1993) notes that the idea of (especially home) places as stable and secure can elide inherent inequalities.

Notwithstanding these concerns, we believe place is a useful organizing construct for developing a cultural geography of health. In a particularly useful formulation, John Eyles (1985) explores the interrelations between place, identity and material life. He describes sense of place as being constituted by two related experiences: that of actual, literal places, and that of ‘place-in-the-world’. With the latter, he refers to the self or externally ascribed status that comes from association with, or occupation of, particular sites. Thus the urban resident may gain a sense of place through both the cumulative experience of urban space (such as his or her own neighbourhood) and the contingent feelings of esteem (or otherwise) that flow from that experience. This view is complemented by a later conceptualization by Entrikin (1991), for whom place is both a context for action and a source of identity, thus poised between objective and subjective realities.

Our specific interest is in the way cultural practices can be observed, and landscapes can be read as ‘text’. We follow Duncan and Duncan (1988: 117) in drawing on Barthes’s attempt to transcend landscape description and to instead ‘show how meanings are always buried beneath layers of ideological sediment’ Place has not universally been viewed in this way within health geography. Kearns and Moon (2001) point out that in Britain, for instance, it has been more of an implicit construct, with a distinction made between context and composition. There has been a tendency to reduce place to space and equate it with the ecological or aggregate (Moon 1990). Perhaps its most obvious manifestation – the study of therapeutic landscapes (places where place itself works as a vector of well-being) – has generated considerable international interest since Gesler’s 1992 paper, with, most recently, the publication of an edited collection with contributors from four countries (Williams 1999). Beyond the work of geographers, the idea of ‘social capital’ has become an implicit expression of the importance of place in the role of supporting and promoting health (e.g. Wilkinson 1996). The population health framework, for instance, illuminates the central role that social geographies of everyday life such as housing, employment and social networks play in shaping health status (Hayes 1999).

What of our place as authors? We write from academic bases in the United States and New Zealand. As Kearns and Moon (2001) indicate, scholarly practice from beyond the non-English-speaking world surely has a place in speaking to us. We must avoid creating a homogeneous view of ‘an Atlanto-Antipodean white health geography orthodoxy’. Yet in supporting this call, we (perhaps ironically) are two white males writing from the aforementioned double-A axis within geographical scholarship. In doing so, we at least advocate bringing into the project those from elsewhere in the academic world. Where possible, therefore, we discuss the work of lesser-known writers and the perspectives of groups whose voice is arguably less heard within the discipline. This may, of course, be only a partial answer to bringing new people and places into the conversation and the need to ‘be audience to them, rather than implicitly expecting them to be audience to us’ (Kearns and Moon 2001: 7).

Health

The adjective ‘medical’ which has conventionally prefixed geographical scholarship concerned with health, disease and therapy has to some extent marginalized our work into a domain perceived as perhaps too niche-like, applied and bioscientific. Health arguably allows an expansiveness that blends the cultural, environmental and social with greater ease. What do we mean by health? In our earlier discussion of ‘culture’, we began the process of considering the range of ‘cultures of health’ that exist. Another useful departure point is the word’s origins in the old English haelth. This derivation involved three meanings: whole, wellness and the greeting ‘hello’ (Lee 1982). The connections between these meanings remain with us today. In Western culture, a glass is raised at dinner and the toast is ‘good health’ Other cultures have more intimate forms of greeting. In Maori protocol, for instance, the traditional greeting is the hongi, in which one’s breath, a necessity of life, is momentarily symbolically shared through the pressing of noses.

The World Health Organization (WHO) (1946) signals this wholeness in its often-cited definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or injury’. This depiction of health has been prefigured in indigenous belief systems such as those of First Nations peoples in Canada (Stephenson et al. 1995) and Maori in New Zealand. For Maori, hauora (health) can be seen as a four-sided concept: the spiritual (taha wairua), the psychological (taha tinana), the social (taha whanau) and the physical (taha tinana) (Durie 1994).

Health is an intrinsically holistic concept and social phenomenon and one which easily becomes one of the ‘metaphors we live by’ (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), with broad application in situations beyond the body and biology (e.g. ‘healthy cities’). Health involves more than personal wellness. It can be a metaphor that can ‘steer place-making activities’ (Geores 1998: 52). In this sense, healing places such as spas and thermal resorts can be promoted as such to the point that healing = place. Here, healing is associated with a bounded area in which therapeutic properties are to be found here but not there. Locations become conceptualized as containers that represent focal centres for healthiness and reputations found in, but not out of, place (Gesler 1992).

As Evans et al. (1994) point out, a vast amount of effort is centred on trying either to maintain and improve health, or to adapt to its decline. A subset of these activities, they say, involves the deployment of economic resources to the production and distribution of health care, that collection of goods and services believed to have a special relationship to health. Our concern is to explore a selection of those aspects of health and health care that contribute to, or are influenced by, place and local cultures. Our attempt to maintain a thematic breadth is consonant with the recognition of the reactive nature of the so-called ‘health’ care system. While we are interested in the cultural and place-specific aspect of sickness care, we recognize that the World Health Organization (WHO) rejected the absence of sickness as a de facto definition of health over forty years ago. The classic WHO definition of health arguably opens space for the cultural geographer to widen horizons to accommodate the blurred boundaries between medical concerns and the lay pursuit of well-being in society.

While ‘progress’ as an ideology is associated with the modernist mindset, the original WHO definition has been interpreted as ‘unwittingly’ postmodern in its depiction of health (Kelly et al. 1993). Paradoxically, the WHO, and agencies and individuals taking up its cause, have invariably opted for technical expertise in the quest for causes of ill health. Yet the positive view of health embedded in the WHO definition begs for an alternative view in which nuance, difference and contingency – hallmarks of postmodernism – surface onto the research agenda.

At the level of the individual, health as progress towards the development of a person’s potential is a worthy goal. While we acknowledge the challenges of measurement, we believe it is better to adhere to a positive and challenging definition than to a contradictory yet measurable one. Health, we believe, must be considered a ‘presence to be promoted and not merely an absence to be regretted’ (Meade and Earickson 2000: 2). An implicitly postmodern perspective on health, anticipated by such commentators as Dubos (1959), celebrates the intangibility of health and, rather than despairing of its inherent relativism, acknowledges its roots in the moral values of individuals and political process. Our book continues a process of ‘making space for difference’ (Kearns 1996) in health geography by embracing an inclusive and expansive view of health.

As citizens and geographers we are both participants in, and observers of, turbulent times. In the health care sector, we witness people disillusioned by the commercial reorientation which sees patients recast as customers and a general striving to reclaim health as a quality less commodified, less medicalized and more connected to everyday life experiences (see Chapter 8). Such concerns, we believe, underlie a reawakening of interest in the notion of therapeutic landscapes (see Chapter 7).

Health is, to a large extent, constructed by the health care systems prevailing at any particular place and time. While the examples we use inevitably are drawn from within health systems, we are not especially concerned with the systems per se. Other recent surveys by geographers aimed at a similar teaching level (e.g. Curtis and Taket 1996) offer a comprehensive assessment of change within major and contrasting health systems such as those in the USA and Britain. In our book, the system is the stage on which relations between culture, place and health are examined, rather than the primary object of interest.

Narrating change

A key influence informing our book is the recent escalation of interest in narrative theory across the humanities and social sciences. This interest suggests a renewed willingness within Western scholarship to ‘trust the tale’ (Kearns 1997c). The narrative turn in health geography has manifested itself in a number of ways. First, there has been a (re)legitimation of the authorial perspective, manifested in the use of the personal pronoun. While perhaps apparently minor in the larger scheme of things, this does symbolize a return to ‘geographer as teller of tales’. This willingness to be candid in reporting research reflects a renewed frankness about the way things are, and the experience of being researchers. Thus the place of safety (Dyck and Kearns 1995) and emotion (Widdowfield 2000) are now part of reflecting on the research process. We all know that personal disposition interacts with pragmatic considerations such as availability of funding or supervision, ultimately influencing choice of topics and approaches. However, as if story has been presumed to be best subordinated to science, there has been scant recognition of such matters. It is thus reassuring to note the personal becoming political at the micro scale of health research (e....

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Culture Matters to Health

- 3 Studying Culture/Placing Ourselves

- 4 Structure and Agency

- 5 Language/Metaphor/Health

- 6 Cultural Difference in Health and Place

- 7 Landscapes of Healing

- 8 Consumption, Place and Health

- 9 Conclusion

- Bibliography