- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides school governors with a blueprint for working effectively and enthusiastically to bring about positive change in their schools, for the benefit of all those concerned.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Making a difference

Effectiveness and improvement

We have to believe that we can make a difference.

(Primary school governor)

Introduction

Being effective means having an effect—making a difference. Research tells us that some schools are more effective than others, i.e. that pupils attending those schools achieve more than pupils attending apparently similar schools. Research also identifies factors that appear to be common to these effective schools. There has been less research into the effectiveness of governing bodies, but what there has been suggests that governing bodies also vary in their effectiveness. However, governors generally want to do a job that is worthwhile and are much more likely to remain on the governing body if they feel that they have a role to play in making a difference. ‘When the governors and head are engaging with the quality issues that matter for the school, such active participation generates positive feelings for all who work there’ (Holt and Hinds 1994:17).

In recent years interest has shifted from trying to identify the factors that contribute to school effectiveness to attempting to understand how schools may be helped to improve, i.e. how to become more effective. No matter how effective a school or a governing body may be, there is always room for improvement. The notion of ‘continuous improvement’—best summarised by the phrase ‘you don’t have to be ill to get better’—is one that underpins the drive for school improvement. The standard of the pupils’ work in one or more subject areas may be significantly below that in other aspects of the curriculum or there may be weaknesses in some aspect of the cross-curricular work, including of course the non-academic work of the school. Governing bodies can improve in the sense that they can become more efficient and more effective in helping their schools to improve.

Effective schools

An effective school can be defined as one in which the pupils progress further than might be predicted from considerations of their attainment when they enter the school.

(Mortimore 1991)

School effectiveness is now usually defined in terms of pupil outcomes. Research (e.g. Rutter et al. 1979, Mortimore et al. 1988, Sammons et al. 1995) has shown that the school which a child attends can make a significant difference to her/his performance. The more effective the school the greater the ‘value-added’ to the pupils’ performance, i.e. the greater the pupils’ attainments in relation to what might have been expected in the light of their past record. Mortimore points to the significance of the 10 per cent difference in a child’s GCSE results that can be made by attendance at a more effective school. Though this variation may appear small it can be the difference that opens up the opportunity of taking A levels and eventual entry into one of the professions. Schools are becoming more skilled in measuring the difference that they make; more reliable and more detailed information (e.g. Qualification and Curriculum Authority (QCA) benchmarking data and Performance and Assessment Reports (PANDAs)) are now becoming available about the performance of their pupils over the years and about the performance of pupils in schools of a similar type (e.g. in catchment area, entitlement to free school meals). Governors and staff together can use this information to set targets for improvement.

How might the effectiveness of a school be judged? The above definition of effectiveness appears to stress academic attainment alone but it might appear foolish to judge a school on only one aspect of its performance. The OFSTED Handbook for Inspections (OFSTED 1994a), well-known to governors and teachers, sets out four criteria by which the overall performance of the school will be judged by the inspectors. These are:

• the standards of achievement;

• the quality of education provided;

• the efficiency with which resources are managed;

• the spiritual, moral, social and cultural development of pupils.

The OFSTED position is that fulfilment of these criteria constitutes effectiveness. A slightly different view is that an effective school is one that maximises the chance of efficient learning taking place in every classroom for every pupil (Reid et al. 1987). If this is the case, what is to be learnt and who decides on this? It may not be easy to arrive at an agreed definition as to precisely what constitutes an effective school; those concerned—pupils, parents, teachers, governors, members of the wider community—may well have differing ideas as to what effectiveness means for them. For some, academic performance alone will be the lodestar, while others may envisage broader objectives covering the whole range of a pupil’s development. Schools should attempt to discover through discussion and debate the views held by the principal stakeholders (Harris et al. 1996). For instance, when the governors of one of the secondary schools involved in our research were involved in a strategic planning exercise, they came up with some rather broader objectives than had been suggested by the teachers. The staff and governors together must then decide, in the light of these discussions, what their priorities and goals should be, and communicate these clearly to all. ‘Governors, head and staff need some shared understanding of what the school is trying to achieve and how it is going about it’ (DES 1991:13).

Lists of factors found in effective schools have been drawn up by a number of authors (e.g. Sammons et al. 1995). These factors include, for instance, shared vision and goals, purposeful teaching and high expectations of pupils. However, none of the lists makes any explicit reference to the impact of the governing body on the school’s effectiveness, though this may be because some, though not all, of the research predates the considerable increase in the powers of governors since 1988. The nearest approach to governors is the recognition that a high degree of parental involvement is present in effective schools. However, From Failure to Success (OFSTED 1997), a report showing how being placed on the register of special measures has helped schools to improve, notes that one of the common characteristics of improving schools is that they have sought means of making their governing bodies more effective. We shall discuss this point further in Chapter 7 which considers the role of the governing body in relation to OFSTED inspections.

The move towards the delegation of control of the school’s budget to the governing body through the Local Management of Schools (LMS) scheme or, previously in the case of Grant-Maintained (GM) schools giving the governing body total control, was part of the previous government’s programme to raise standards of attainment in schools. ‘If the system itself were changed to one of self-governing, self-managing, budget centres, which were obliged for their very survival to respond to the “market”, then there would be an in-built mechanism to raise standards’ (Sexton 1987:8–9). These moves, which might have been expected to provide opportunities for governing bodies to have greater influence in the running of their schools have, however, often led to increased power in the hands of the headteacher. For example, Levacic (1995) found in her research that the majority of the governing bodies were operating in the advisory and supportive roles, and that they were in an unequal partnership with the head. Similarly, Shearn and his colleagues (1995a, 1995b) found that in the majority of the schools, the head was essentially in charge with the governors having little impact upon the school’s direction. In some cases this was with the approval of the governors and in others it arose by default because the governors were unwilling or unable to take on their new responsibility. In a few cases, the headteacher had out-manoeuvred the governors in order to retain control.

Effective governing bodies

There has been much less research into what constitutes an effective governing body than there has been into the effectiveness of schools. Neither has the link between the effectiveness of the governing body and the effectiveness of the school been clearly demonstrated. ‘We cannot assume a priori that if a governing body becomes skilled at discharging its responsibilities, this necessarily means that the school becomes more effective or more efficient’ (Deem et al. 1995: 112).

Governing Bodies and Effective Schools (DFE/BIS/OFSTED 1995) lists the main features of an effective governing body as being:

• working as a team;

• having a good relationship with the headteacher;

• managing time and delegating effectively;

• having effective meetings;

• knowing the school;

• being concerned for their own training and development.

Creese (1995) suggests that, in addition to these, an effective governing body is one which:

• works in partnership with the staff;

• is concerned to promote school improvement;

• forms an effective link between the school and the community.

During inspections of schools carried out during the spring term of 1998, OFSTED inspectors assessed the performance of governing bodies particularly in relation to the performance of their strategic role. Those governing bodies given a good grading were those where the complementary roles of the governors and senior managers were well-defined and evident through good practice; where the governors were highly influential in setting aims and targets for their school and where they identified financial and other priorities, and monitored progress towards achieving them. The inspectors found that the performance of three-quarters of the governing bodies was satisfactory or better, with governors in secondary schools doing slightly better at reviewing progress in their schools than their primary colleagues. One-third of governing bodies were totally reliant upon the information that they received from the headteacher and senior staff as a basis for making their judgements.

Michael Tomlinson, Director of Operations at OFSTED, speaking at a conference for governor trainers in Cardiff in September 1998 stated that the best cases of effective governance found during the survey shared the following characteristics:

• influential heads who responded well to constructive criticism;

• the relationship between governors and staff was well understood by all—especially the staff;

• there was a rigorous approach to the monitoring of standards of education;

• success in reaching present targets was carefully evaluated and challenging targets for the future were set.

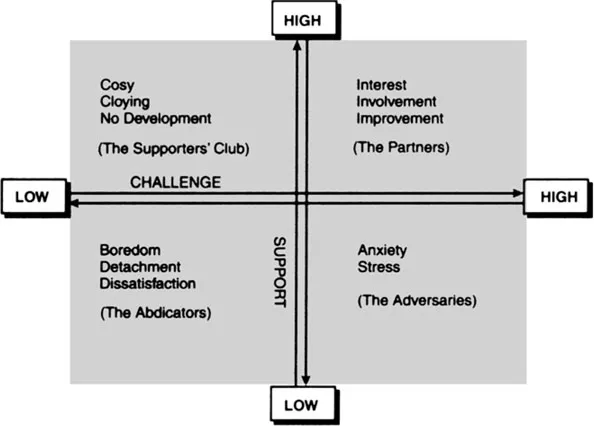

One way of considering the performance of a governing body is to assess it on two criteria, the level of support that it gives to the school and the level of challenge that it provides. This is shown in Figure 1.1, which is based on the ‘Effective Governing Body Exercise’ (Oxfordshire LEA 1998).

Figure 1.1 The effective governing body

Some governing bodies—the abdicators—offer neither support nor challenge to their schools. The supporters’ clubs offer a lot of support but little challenge while the adversaries offer little support but challenge the staff at every opportunity. Ideally, the governing body is working in partnership with the staff offering a great deal of support but not being afraid to ask the teachers to account for their actions. The four types of governing body may be characterised as follows:

The abdicators

Key phrase: ‘We leave it to the professionals.’

These governors claim to be very busy people; they aren’t able to get into school as often as they would like. They don’t have time to go to training sessions—in any case they believe that it’s all common sense really and the money is better spent on books for the children. They believe that they have a good head and leave it all to her/him.

The adversaries

Key phrase: ‘We have to keep our head up to the mark.’

These governors visit the school very often, sometimes without warning, and keep a very close eye on all aspects of the work of school. They are frequently very critical of what they see and they seek to make all the decisions about the running of the school.

The supporters’ club

Key phrase: ‘We’re here to support the head.’

These governors have delegated control to the head who ta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Making a difference: Effectiveness and improvement

- 2. The efficient and effective governing body

- 3. The governing body, the curriculum and teaching and learning

- 4. The role of the governing body in strategic planning

- 5. Target-setting and school improvement planning

- 6. Governors’ role in review, evaluation and monitoring

- 7. The governing body and OFSTED inspections

- 8. The governing body and parents, pupils and the community

- 9. Accountability and the governing body

- 10. Towards school and governing body improvement

- Appendix: the schools involved in the study

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Improving Schools and Governing Bodies by Michael Creese,Peter Earley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.