![]()

Chapter 1

The Hasag Enigma

The Early Days—From Lamps to Mortar Shells

Testifying before the Nuremberg court on July 31, 1946, Oswald Pohl, the head of the SS-Wirtschaftsverwaltungshauptamt, SSWVHA (SS Economic and Administrative Main Office), admitted that the Hasag Concern was the third largest private industry to employ prisoners of concentration camps, surpassed only by Herman Goering Werke and I.G. Farbenindustrie. This is a very surprising statistic, since unlike the industrial giants dominating the German economy, Hasag was a relatively modest enterprise. It is equally odd that as late as the summer of 1944, Hasag was the only firm which still operated six Jewish slave labor camps, among them Skarżysko-Kamienna, in what was by then a Judenrein Gen-eralgouvernement.

What was the nature of this concern and what was the secret of its success in the most problematic of realms—Jewish labor? Why did Himmler refrain from demolishing the Hasag camps as he did all the others? The extensive literature on the munitions industry in the Third Reich could provide no answers to these questions: the name Hasag is either totally absent, or merits only a few short lines. Scholars of the Holocaust to whom I turned for advice had never heard of it. Why is there so little information on this mysterious company?

In the course of my search, I came across a book entitled “Die Hoellevon Kamienna” in which the journalist Hans Frey reports on the trial in Leipzig in 1948 against Hasag employees. According to Frey, in April 1945, when the Allied forces stood at the gates of Leipzig, the outskirts of the city were shaken by a tremendous blast: the main Hasag building was reduced to a pile of rubble. From word of mouth it was soon learned that the general manager of Hasag, Paul Budin, had set the explosion and was himself buried under the ruins. In the process, the entire archives and all of the company documents were destroyed. What secrets was Budin trying to hide from future researchers? Must this question remain eternally unanswered what with the my stery of Hasag literally nothing but dust and ashes? No, a tenacious search through archives in Germany, Poland and Israel can provide a solution, if only a partial one, to the riddle.

The Hasag Concern had a modest beginning. In 1863 a lamp factory by the name of Haeckel und Schneider was founded in Leipzig. In the 1880s, the plant was converted into a metalworks, and in 1899 the Hugo Schneider Stock Company (Aktiengesellschaft) was established. The First World War hastened the growth of the firm so that in 1930 its annual turnover was in excess of five million marks.1 With Hitler's rise to power and the inception of the “Four Year Plan” in 1933, new regulations were issued in July of that year regarding compulsory cartelization. It was made clear to thousands of small and middle-sized companies that their continued independent existence would be assured only if they found themselves a patron. One such was the army of the Third Reich. Paul Budin, a spirited SS functionary, had been appointed general manager of Hasag in 1932.2 He was a shrewd businessman who quickly understood the implications of the new regulations. In 1934 he converted part of the plant to munitions production and simultaneously established a close relationship with the director of the ordnance division of the Ground Forces Armaments Office (Heereswaffenamt-HWaA), General Emil Leeb.3 That very year, Hasag was granted the status of a military plant (Wermachtbetrieb), beginning a new chapter in its history.

In August, 1936, the second “Four Year Plan” (Vierjahresplan— VJP) was issued. One of its stated aims was to “speed up the arming” of the military.4 Since this objective directly relates to the development of the Hasag Company, let us consider briefly the various approaches to the Third Reich's armament policy.

- The ideological-political approach of Goering was based on Hitler's Blitzkrieg strategy and advocated the need for the recruitment and arming of the greatest possible number of new army units (“broad arming”— Breiteruestung) with a stress on the technological development of munitions.

- The professional military approach represented by General Georg Thomas, the head of the Economy Armament Office of the Wehrmacht's High Command (Wehrwirtschafts undRuestungsamt im OKW-Wi RueAmt), warned against the illusion of a Blitzkrieg and called for the increased mass production of personal weapons (“deep arming”—Tieferuestung) in order to insure the supply of munitions and replacement of worn parts.5

The clash between these two camps had direct bearing on the resulting rivalry between the two forces controlling the implementation of armament policy: the army and industry. In principle, following a tradition dating back to the Prussian war, the military was responsible for arming its divisions. In 1933, the Military Economy Command (Wehrwirtschaftsstab—WWiStab) was established, and was charged, among other functions, with supervision of the armaments industry. To this end, a network of Armament Inspectorate Units (Ruestungsinspektion) and Armament Commands (Ruestungskommando) were set up.6

Industrial circles took a stand against the Wehrmacht's desire to assume control of armament production planning. These groups, however, suffered from a time-honored contest for control of the German economy waged between the iron, steel and coal monopolies on the one hand, and the chemical industry giants led by IG-Farbenindustrie on the other. Both industries were involved in the production of weapons, particularly ammunition, and each sought to dominate the planning and implementation stages of the process. With a lack of coordination between the two branches of industry, many firms refused to accept orders from the army for fear of production problems. Thus Hasag's consistent reliability in munitions production strengthened the ties between the company and General Leeb. At his recommendation, Hasag was chosen to supply arms to the air force as well.7 Paul Budin's organizational and financial skills soon earned him the nickname “Economic Strategist of the SS.”8

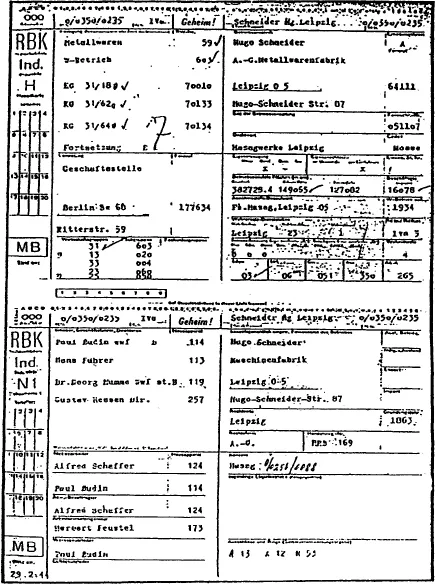

What were Hasag sources of capital and who were its stockholders? According to the list of Hasag stockholders from 11th October 1943, 80% of the stock kapital was in the hands of three financial institutions: Deutsche Bank, Allgemeine Deutsche Credit Anstalt (ADCA) and Dresdner Bank.9 Hasag had a specially close link with the latter two, as is obvious from the composition of the six-members Board of Directors (Aufsichtsrat): the Chairman Dr. Ernst von Schoen von Wildenegg and Felix Basserman who were also members of the Board of Directors of ADCA, Hugo Zinsser and Adolf Hartman, both managers in Dresdner Bank, Carl Hoehn and dr Richard Koch.10 The direction (Vorstand) of Hasagwerke-Leipzig included Paul Budin as general manager and his three assistants: Gustav Hessen, Dr. Georg Mumme and Hans Fuehrer (see Figure 1.1).11

Budin was supposed to consult with the board members on all major matters, including the appointment of managers to the firm's subsidiaries, and his signature alone was not sufficient on contracts and appointments. In practice, however, the decisions were his, and were approved on the plants outside of Leipzig, and did not invite his partners to join him retroactively by the board and directors. He was not in the habit of reporting on his visits there. To give him credit, Budin always seemed to find the right person for the right job, and he brought together a very loyal staff.

Figure 1.1 The “Reich's Factory Card” of Hasagwerke–Leipzig February 1944 (Reichsbetriebskarte Hasagwerke–Leipzig, BA, R3/2014)

As an SS-Sturmbannfuehrer, he often appointed members of the SS to executive posts in the Hasag plants,12 but when it came to blue-collar workers, he looked only for professional skills, even hiring former communists. He thus created a team of shop stewards ready to lay their lives on the line for Hasag.

As a devout Nazi, Budin could claim that “Hasag is me.” Under his management, the company prospered. By 1939, its annual turnover had reached 22 million marks and its work force had grown to 3,700. With the granting of the status of official munitions plant (Ruestungsbetrieb), Hasag was ready to begin economic operations in the occupied lands as well, and this led to a dizzying boom. In February, 1944, the company's plants in Leipzig alone employed 16,078 workers. For his achievements, Budin was dubbed “Leader of the War Economy” (Wehrwirtschaftsfuehrer), and in 1944 Hasag-Leipzig was awarded the status of Model National-Socialist Factory (Nationalsozialistischer Musterbetrieb).13

This, then, was the company and the man who were “waiting in the wings” when the Wehrmacht invaded Poland in 1939, ready to follow up the military rout with an economic rout.

The Debate Over the Fate of the Polish Armaments Industry and its Consequences

With the outbreak of the war, arming the military became the primary objective of the “Four Year Plan,” and it was against this background that the future role of the Polish armaments industry became the subject of debate immediately following the occupation of that country. Goering, as agent of the VJP, represented Hitler's doctrine designating Poland for military and political annihilation,14 and thereby demanded the dismantling and transfer of all plants vital to the German economy, including, of course, munitions factories, to the Reich. This demand was founded on economic grounds: Poland's swift defeat was seen as proof that the end of the war was near and so there would no longer be a need to expand armament production. With the war over, there might be widespread unemployment and the Polish munitions industry could develop into a competitor to German concerns.

The Wi Rue Amt, headed by General Thomas, was opposed to this liquidation program. The Wehrmacht viewed the Polish armaments industry, as they did that within the Reich itself, as one of the cornerstones of its power, and thus advocated its continued existence under Wehrmacht supervision and control. Fearing that the war would spread to two fronts, Thomas demanded that the industrialists step up military production,15 and considered the Polish munitions plants an important back-up in light of the danger of aerial bombing of Germany. When England declared its embargo, however, Goering altered his position. At a meeting held on December 4, 1939, it was decided to promote the armaments industry in the Generalgouvernement, particularly in the southern region which included the district of Radom (see Figure 1.2).16

At this same time, the WWiStab began to take several practical measures. In December, 1939 the Armaments Inspectorate— Eastern Command—was established in the Generalgouvernement and its major tasks defined as: accepting orders from the Wehrmacht divisions and distributing them among the various munitions plants, responsibility for the external and internal security of these plants, and supply of manpower to the factories where necessary. The post of inspector of armaments was given to General Barckhausen, with his headquarters in Krakow, and three Armament Commands under his authority in Warsaw, Krakow and Radom. A “technical squad” was set up in each of the army divisions charged with seizing and controlling factories and other facilities vital to the military.17 The squad patrols relied on precise intelligence, which included extensive information on the munitions factories in Poland.

The “Assessment of Polish Economic Strength” of September 25, 193...