![]()

Part I

Prehistoric, Roman, and Anglo-Saxon Britain

The physical features of the British Isles

![]()

Chapter 1

The Land and Peoples of Early Britain

Geography of the British Isles

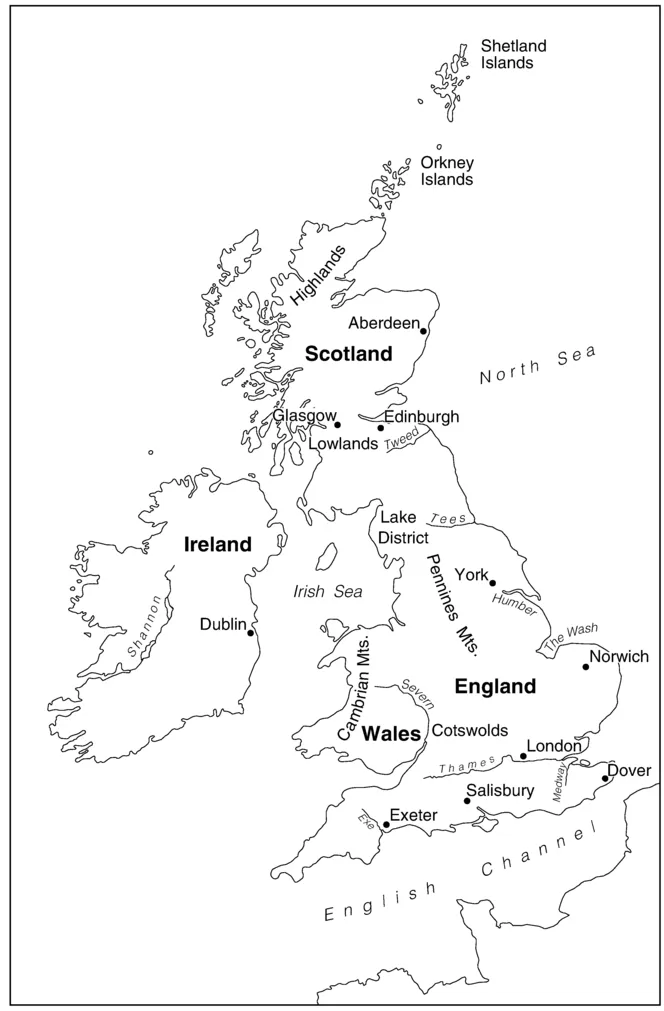

Because the development of any country is determined in part by its physical setting, a history of the British Isles must begin with a short description of the geography of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland.

Students are often surprised at the small size of these areas. England proper contains only about 50,000 square miles. Wales, much smaller, adds only another 7,500. Thus the land ruled by the kings of England before 1603 was smaller than most American states. Scotland has a land mass of about 30,000 square miles, Ireland about 27,000.

Because Britain has been such an important world power, actively involved in colonization and international trade, its location is also surprising. England is not central to the great continents of Europe, Asia, or North America. It lies farther north than any part of the United States except Alaska and any great capital except Moscow. London is at about the same latitude as Newfoundland, not as New York, which is more central. Britain’s temperate climate is determined by the nearly constant temperature of its surrounding waters and by the warmth carried to its shores by the Gulf Stream.

Each part of the British Isles has its own physical characteristics. England can be divided into two halves by drawing an imaginary line diagonally from the mouth of the River Exe, near Exeter in the Southwest, to the mouth of the River Tees in the Northeast. Most of the fertile soil in the country lies in the lowland zone to the southeast of this line. The land is flat or gently rolling, with low hills and long navigable rivers, the most important of which, the Thames, determined the location of the great city of London. As long as English society was primarily agrarian, before the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century, the bulk of the population lived in this area.

Northwest of the Exe-Tees line is a highland zone where the land is rocky and mountainous, more suitable for pasture than for intensive cultivation. Rivers are short and generally not navigable for great distances; some have rocky shoals or waterfalls. The famous Lake District, nestled in the Cumbrian mountains, boasts England’s most spectacular scenery. Until recent times, communication between the east and west coasts was made difficult by the Pennine chain of mountains, which bisects northern England. Wales shares this infertile land. Its terrain includes lush valleys as well as the craggy Cambrian mountains.

That Scotland developed its own civilization and government, separate from England, is largely explained by the band of barren moorland that forms the border between the two countries. Farther north the Scottish Lowlands include fertile soil, rolling wooded hills, sparkling streams, and a chain of lakes, one of them reputedly the home of the Loch Ness monster. The bulk of the Scottish population has long lived here, in the cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Still farther north are the Highlands, the traditional home of the clans with their kilts and bagpipes. It has always been difficult for even a small number of people to eke out a living from such inhospitable surroundings, beautiful though they are.

Ireland’s saucer shape includes areas of bog and marsh as well as woodland and some very fertile tillable soil. Mountains are concentrated near the coast; the central lowlands dominate the island. The Shannon is the longest river in the British Isles, flowing down the western coast of Ireland for more than 200 miles, but it is not the heart of a great river system, and it has not been of much economic value. Rainfall is heavier than in England. Frost and snow are almost unknown in the interior of the island. The capital, Dublin, lies on the east coast facing Britain. Separated from the larger island by the Irish Channel, on an average about 50 miles wide, Ireland has developed its own unique civilization, frequently dominated by Britain but never integrated racially or culturally.

Prehistoric Britain

Historic times begin with the availability of written records. Peoples who do not read and write, no matter how advanced their civilization may be in other ways, live in the prehistoric era. Because literacy is the criterion, the end of prehistory came at different times in different parts of the world. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans produced written documents long before the beginning of the Christian era, while prehistoric cultures lasted until recent times among Native Americans and in several Third World areas. The Romans produced the earliest written records describing Britain at about the time of their first invasion in 55 B.C., so prehistoric times are usually said to end in that year.

It may seem paradoxical to talk of the history of prehistoric peoples, yet thanks to the science of archaeology a good deal is known about prehistoric life in the British Isles. Archaeologists usually divide the long spans of time they cover into periods on the basis of the material used for implements and weapons. Thus they speak of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Different dates for these eras apply in different parts of the world.

Archaeologists work by digging. Human beings, fortunately from this point of view, are notoriously messy, and merely sifting through our trash reveals much about our way of life. If a trench is dug in an area that has been continuously inhabited since prehistoric times, the top layers consist of objects deposited in recent

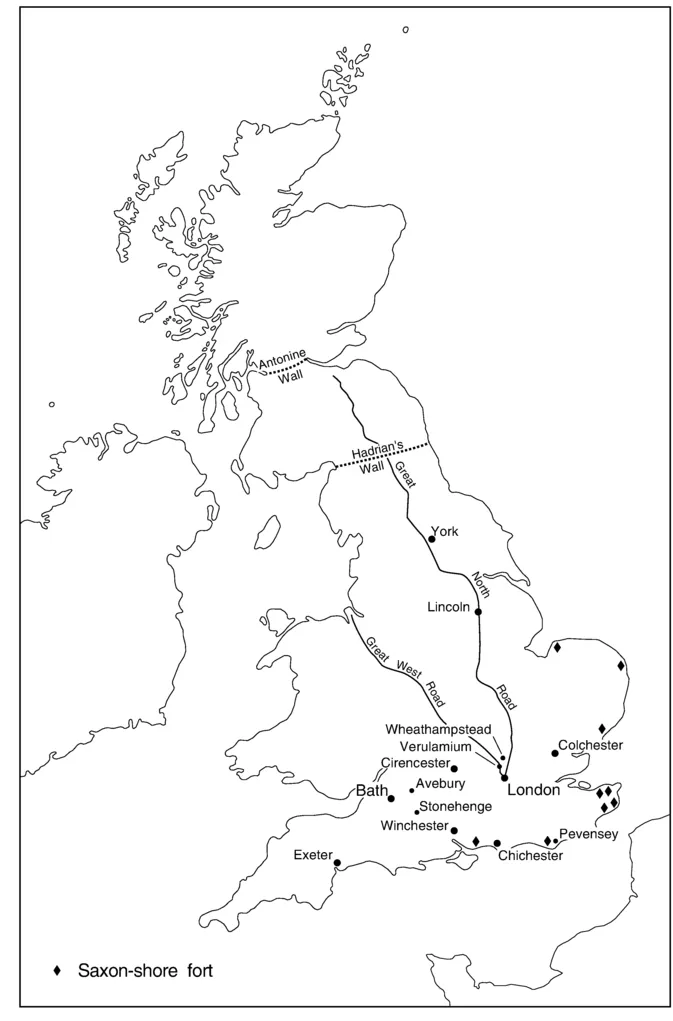

Prehistoric and Roman Britain

years. Lower down the digger may find medieval artifacts, and still lower the remains of prehistoric settlements. Objects from different sites can be classified on the basis of burial customs and the artistic style used in ornamenting pottery, and they can now be dated scientifically by the use of carbon 14. A radioactive form of carbon, this has a known half-life, and any object that was once living, such as a bone or woolen textile, can be given an approximate date by measuring the remaining radioactivity. Increasing use of carbon 14 tests, together with techniques involving analysis of tree rings and pollens, has led to a revolution in archaeological dating during the last decade or two. Many developments are now thought to be earlier than was previously believed.

The earliest known part of a human skeleton found in the British Isles is the so-called Swanscombe skull, excavated in southeast England in 1935. It is probably the head of a woman. It cannot be dated by carbon 14, which is not effective for articles more than about seventy thousand years old, but archaeologists believe that it comes from a period about 200,000 B.C. Some coarsely worked hand axes found nearby may be even older, perhaps as early as 300,000 B.C. During the late nineteenth century, it was believed that an apelike skull unearthed at Piltdown was the earliest example of human life in Britain and that it supported Darwin’s theory of evolution. We now know that this was an elaborate hoax: in fact it is a human skull of no great antiquity joined to the jawbone of an ape. The earliest human remains so far found in Scotland and Ireland are dated much later, about 17,000 and 10,000 B.C. respectively.

The Stone Age, in which implements were fashioned of stone rather than metal, lasted from about 200,000 B.C. to about 2000 B.C. This long period can be divided into the Paleolithic, or old stone age; the Mesolithic, or middle stone age; and the Neolithic, or new stone era. At the beginning of Paleolithic times, the climate in Britain was mild, so men and women could live without clothes or shelter. Then the glaciers descended, and the inhabitants responded by making simple clothing from animal hides and by seeking shelter in caves. They also learned the use of fire, probably discovered accidentally when sparks fell from pieces of flint onto piles of dry leaves. Excavations at Skara Brae, a well-preserved settlement in the Orkney Islands off the Scottish Coast, have uncovered soundly built homes with inside lavatories dating from about 3000 B.C.

Recent research suggests that the Neolithic age began about 4000 B.C., considerably earlier than previous writers believed. During this period a milder climate returned, but the advances taught by necessity remained. A culture group called the Windmill Hill people crossed the Channel (perhaps then no more than a wide river) from northern Europe about 3000 B.C., bringing with them a way of life that included settled agriculture, the keeping of such domestic animals as sheep and dogs, the use of well-shaped flint arrowheads, and the making of pottery ornamented with spiral or thumbprint designs. The skeletons of their dead were buried intact (this is called inhumation, as opposed to cremation, the burning of remains), usually in groups rather than individually. Long mounds or “barrows,” strikingly similar to the burial mounds of Native Americans, were erected over these burials. Today, especially when viewed or photographed from the air, they help identify sites where the Windmill Hill culture was established. The culture spread to Yorkshire, in northern England, and to Ireland.

A later Neolithic group, the Beaker Folk, migrated from northern Europe, probably between 2500 and 2000 B.C. Their name derives from the characteristic shape of their pots, which resemble the beakers used in chemistry laboratories. Such pottery has been found at sites throughout England, Ireland, and southern Scotland. The Beaker Folk usually buried their dead singly, in round barrows. The earliest known textile from the British Isles was found in one of these. Beaker sites have also yielded bronze drinking cups and jewelry, but these articles were probably acquired by trading with more advanced peoples on the Continent. A few settlers in England may have learned how to work in metal by this time, but the Beaker Folk do not seem to have known how to produce metal articles themselves.

The Bronze and Iron Ages

During the Bronze Age (now dated about 2000 to 1000 B.C.), the art of working bronze came to the British Isles. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, has a low melting point and thus is easier to handle than iron. It is also more attractive for decorative objects, but because it does not take a hard cutting edge it is less useful for knives and weapons like swords or axes. The most important Bronze Age group, usually called the Wessex Culture, came from the Continent to southwest England but soon spread throughout the British Isles. These invaders brought with them their skill in producing bronze articles. Some of the existing inhabitants may also have acquired the ability to work metal. Archaeologists used to attribute each technological leap to a fresh wave of immigrants from the mainland of Europe, but new work suggests that some advances were a natural, native growth. The dead of the Wessex Culture were cremated, with an urn being inverted over the remains; burials might be single, in mounds, or grouped, in urnfields. Objects from as far away as Egypt and Greece have been found in these burial sites, proof that the Wessex people were involved in international trade.

The art of working iron came to Britain about 1000 B.C. Bronze continued to be used for ornamental objects, with gold and silver also available in small quantities, but iron superseded bronze for utilitarian purposes. Large-scale settled farming was now practiced, with corrals, threshing floors, and store-houses or barns, and additional forested land was cleared for agricultural use. Recently, an interesting attempt has been made to recreate an Iron Age farm at a site in southern England (Butser, in the county of Hampshire). Here ancient breeds of sheep, pigs, and cattle (similar to the extinct Celtic Shorthorn) are raised, and a range of cereal crops, notably several varieties of wheat and barley, are grown. The environmental archaeologists involved in this experiment use only implements and farming techniques that would have been available in prehistoric times.

Stonehenge

The most imposing monument remaining from prehistoric Britain is undoubtedly Stonehenge. This great stone circle—actually it is several concentric circles of stones—was erected on Salisbury Plain, near the middle of the south coast of England. Work on the site may have begun as early as 2500 B.C. The initial construction of the great circle can be attributed to the Beaker Folk, with modifications and additions by later peoples between 1900 and 1400 B.C. About 300 feet in diameter, it includes a set of enormous uprights weighing as much as 50 tons each, quarried near the site, and sixty smaller bluestones, hewn from the mountains of Wales and transported, probably mainly by water, for 135 miles.

Scholars remain undecided about the reasons why this great monument was created. The alignment of stones suggests that it had something to do with sun worship, though notions of white-robed Druids dancing by moonlight or exacting human sacrifice may be dismissed as romantic inventions unsupported by hard evidence. One recent theory, advanced by the physicist Gerald Hawkins, holds that Stonehenge was actually an observatory, use...