eBook - ePub

Flash Cinematic Techniques

Enhancing Animated Shorts and Interactive Storytelling

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Apply universally accepted cinematic techniques to your Flash projects to improve the storytelling quotient in your entertainment, advertising (branding), and educational media. A defined focus on the concepts and techniques for production from story reels to the final project delivers valuable insights, time-saving practical tips, and hands-on techniques for great visual stories. Extensive illustration, step-by-step instruction, and practical exercises provide a hands-on perspective.

Explore the concepts and principles of visual components used in stories so you are fluent in the use of space, line, color, and movement in communicating emotion and meaning. Apply traditional cinematography techniques into the Flash workspace with virtual camera movements, simulated 3d spaces, lighting techniques, and character animation. Add interactivity using ActionScript to enhance audience participation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Flash Cinematic Techniques by Chris Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Informatica & Media digitali. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Show, Don’t Tell Me a Story

Animation is all about showing, not telling a story, but what makes a story good? A good story needs a compelling plot that involves appealing characters living in a believable world. Understanding the story structure and how to visualize it using Flash is the topic of this first chapter.

Anatomy of a Story

The Story Structure

Make Every Scene Count

Show, Don’t Tell

Find Your Artistic Direction in Flash

Anatomy of a Story

Stories always start with an idea. Ideas can come from all around you—from your imagination, personal observations, life experiences, to your dreams and nightmares. These random thoughts or observations are recorded as events. Events are then woven together to formulate the story’s plot.

The plot is not the story itself; it is all of the action that takes place during the story. How the action affects the characters physically and emotionally builds a good story. The fundamental components to any story involve a character or characters in a setting, a conflict that causes change, and a resolution that depicts the consequences of the character’s actions.

Take a look at the following nursery rhyme:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall;

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the King’s horses and all the King’s Men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

Deceptively simplistic in nature, this nursery rhyme contains all of the necessary building blocks to tell a story (Figure 1.1). The first line establishes the main character in a setting. The second line introduces conflict by having the character fall. A change occurs with all the King’s horses and men coming to Humpty’s aid. The last line is the resolution; the main character remains injured as a result of his actions. The story is simple, but is it compelling? Perhaps not.

Humpty Dumpty is a one-dimensional character. He exhibits very few characteristics that an audience can relate to. Let’s add some element of interest to the rhyme. What if Humpty Dumpty was warned by his mother not to sit on the wall, but disobeyed? What if Humpty Dumpty was depressed and deliberately jumped? What if all the King’s Horses and all the King’s Men secretly conspired to get rid of Humpty (Figure 1.2)? Now the story takes on more meaning for the audience. Their curiosity is piqued as they seek out answers from the storyline.

A good story is judged by the emotional impact it has on its audience. Adding interest to your story triggers this emotional response. Audiences want to be able to relate to the characters. Once bonded, audience members experience the turmoil the characters go through by projecting themselves into the story. Audiences also anticipate the dramatic tension created by the conflict and want to know what is going to happen next. Without any emotional involvement, a story is reduced to a series of events.

Storytellers typically employ a dramatic story structure to determine when certain events will happen to achieve the greatest emotional response from the audience. This structure can be applied to a three-hour movie or to a 30-second commercial. Developed by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, it has become the narrative standard in Hollywood. Audiences are quite familiar with it and even come to expect it.

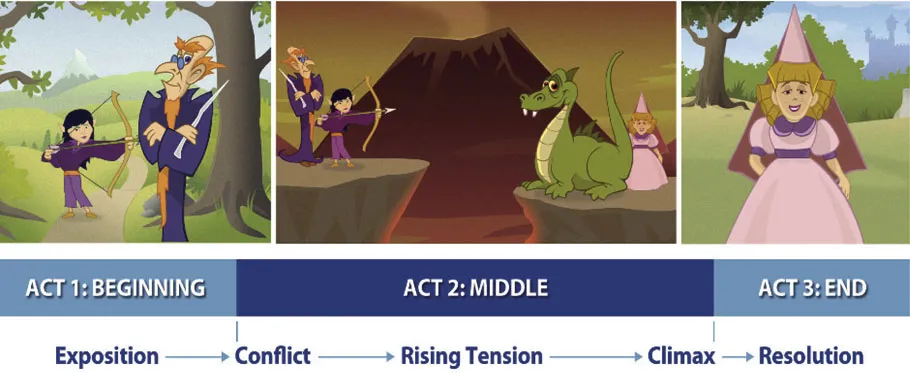

The Story Structure

The dramatic structure consists of a beginning, middle, and an end (Figure 1.3). Each act applies just the right amount of dramatic tension at the right time and in the right place. Act One is called exposition and it gives the audience information in order to understand a story. It introduces the setting, the characters, their goals, and the conflicting situation that the story is about.

The setting is where and when the story takes place. When developing your story ask yourself where is the story set: on another planet? in a car? underwater? Does the story occur in the past, present, or future? With the setting in place, you next need to populate your world with characters. It is important to note that the world, its timeline and occupants, all need to be believable to the audience. That doesn’t mean it has to be realistic. Walt Disney summed it up best with the term “plausible impossible.” It means that it is something impossible in reality but still can be convincingly portrayed to the audience.

There are often two types of characters in a story: the hero (protagonist) and the villain (antagonist). The hero is the main character and has a strong goal that he must achieve without compromise. The villain will stop at nothing to prevent the hero from succeeding. Audiences typically root for the hero as he faces a series of ever-increasing obstacles created by the villain. The opposing goals of the hero and villain create the story’s conflict.

Act Two focuses on the conflict. Conflict is the most important element in a story. The problems faced by the characters make the story exciting. The key to creating good conflict is to make the villain stronger than the hero at the beginning. Usually the villain is another person, but can be an animal, nature, society, a machine, or even the hero himself battling an inner conflict. Throughout the story, the villain needs to pursue his own goal as actively as the hero. Audiences love a great villain who is as complex and interesting as the hero.

If the hero can easily beat the villain, you don’t have a good story. In order to engage the audience emotionally, they must empathize with the hero. The hero should be someone the audience can feel something in common with, or at least care about. Empathy links the hero’s challenges and experiences to the audience. One way to do this is to give the hero certain weaknesses at the beginning of the story that can be exploited by the villain. These weaknesses drive the conflict and raise the audience’s emotional connection or bond to the hero. As the character wrestles with the conflict, the audience wrestles with him and cares about the outcome (Figure 1.4).

Act Two drives the story forward raising the tension. The villain constantly creates new obstacles causing the hero to struggle towards his goal. The tension reaches a high point at the end of Act Two. This is also referred to as the climax or turning point, when the plot changes for better or for worse for the hero. During this moment, the hero takes action and brings the story to a conclusion.

Act Three is the resolution and end of the story. It resolves the conflicts that have arisen. Act Three ties together the loose ends of the story and allows the audience to learn what happened to the characters after the conflict is resolved. This is often referred to as closure. Storytellers often start developing stories by figuring out the climax or the conclusion of the story and then work their way backwards.

This dramatic structure provides a framework for a story. Stories created in Flash tend to be less complex than feature films or even television shows. Usually these are short stories that focus on only one incident, have a single plot, a single setting, a couple of characters, and cover a short period of time.

As you begin developing your story in Flash, decide what the audience needs to know and when to add the dramatic tension. Start by showing a path for the audience to follow. Give them visual clues to what is going on in the opening scene. With the compressed format in Flash, it makes cutting to the chase all the more essential.

Make Every Scene Count

Understanding story and its structure is important, but you are working in a visual medium. As a visual storyteller, you can enhance a story’s emotional experience by showing how a story unfolds through a sequence of images. However, creating beautiful imagery is not enough if the visuals do not reinforce the story’s narrative or meet the audience’s expectations.

For each scene in your story, you need to visually answer the following three questions that audience members ask. They are:

1. What is going on?

2. Who is involved?

3. How should I feel?

Most stories created in Flash range from 30 seconds to two minutes in duration. That is not a lot of time to divulge a complex plot. You need to make every scene count by either advancing the story or developing the characters. It is best ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Show, Don’t Tell Me a Story

- Chapter 2: Get into Character

- Chapter 3: Give Me Space

- Chapter 4: Direct My Eye

- Chapter 5: Don’t Lose Me

- Chapter 6: Move the Camera

- Chapter 7: Light My World

- Chapter 8: Speak to Me

- Chapter 9: Interact with Me

- Chapter 10: Optimize and Publish

- Index