![]()

CHAPTER

The Shooter’s Point of View | 1 |

Dear Video Shooter:

This is your task. This is your struggle to uniquely and eloquently express your point of view. Whatever it is. Wherever it takes you. For the shooter-storyteller, this exploration can be exhilarating and personal. It’s what makes your point of view different and enables you to tell visually compelling stories like no other video shooter in the world.

In May 1988 while on assignment for National Geographic in Poland, I learned a profound lesson about the power of personal video and point of view. The aging Communist regime had amassed a thousand soldiers with tanks in front of the Gdansk Shipyard to crush a strike by workers belonging to the banned Solidarity union. I happened to be shooting in Gdansk, and despite it not being part of my assignment I ventured over to the shipyard anyway in light of the world’s attention being focused there and the compelling human drama unfolding inside.

Out of sight of my government minder, I understood I could’ve been beaten or been rendered persona non grata, but I took the chance anyway as I was convinced that history was in the making. The night before, the military had stormed a coalmine in southern Poland and had brutally beaten many strikers as they slept. Not a single photo or frame of video emerged to tell the tale, but news of the carnage spread anyway through unofficial channels. The shipyard workers figured they were in for the same fate, and I wanted to record it.

Considering the regime’s total control over the press and TV, it was no surprise that the Polish InterPress Office would deny my 16mm Arriflex and me access to the shipyard. But that didn’t stop my two Polish friends with less obvious video gear from slipping inside the complex in the back of a delivery van.

Throughout the previous fall and winter, Piotr Bikont and Leszek Dziumovicz had been secretly shooting and editing half-hour newsreels out of a Gdansk church loft. Circumventing the regime’s chokehold on the media, the two men distributed the programs through a makeshift network of church schools, recruiting young school kids to ferry the videocassettes home in their backpacks.

As this latest shipyard drama unfolded, Piotr and Leszek vowed to stay with the strikers to capture the assault and almost certain bloodbath. Piotr’s physical well-being didn’t matter, he kept telling me. In fact, he looked forward to being beaten, provided he could get the footage out of the shipyard to me, and to the watchful world.

But for days and weeks the attack didn’t come, and Piotr and Leszek held their ground, capturing in riveting detail the exhaustion of the strikers as the siege dragged on. In scenes reminiscent of the Alamo, 75 men and women facing almost certain annihilation held firm against a growing phalanx of tanks, troops, and feckless provocateurs who occasionally feigned an assault to probe the strikers’ defenses.

In the course of the siege, Piotr and Leszek made a startling discovery that their little Sony camcorder could be a potent weapon against the amassed military force. On the night of what was surely to be the final assault, the strikers broadcast a desperate plea over the shipyard loudspeakers: “Camera to the gate! Camera to the gate!” The strikers were pleading for Piotr and Leszek to come with their camera and point it at the soldiers. It was pitch dark at 2 a.m., and the camera couldn’t see much. But it didn’t matter. When the soldiers saw the camera pointed at them, they retreated. They understood the inevitability of a postcommunist Poland and were terrified of having their faces recorded!

FIGURE 1.1

Solidarity activists Piotr Bikont and Leszek Dziumowicz with the Sony camcorder that helped transform the face of Eastern Europe in the 1980s.

As the weeks rolled by, the strikers’ camera became a growing irritant to the authorities. Finally, in desperation, a government agent posing as a striker ripped the camera from Piotr’s arms. After a frantic chase, the agent ducked into a building housing several other agents, not realizing, incredibly, the camera was still running!

Inside a manager’s office, we see what the camera sees: a drab blank wall as the camcorder pointing nowhere in particular dutifully records the gaggle of agents plotting to smuggle the camera back out of the shipyard. The camera is then placed inside a paper bag, and the story continues from this point of view: The screen is completely dark as the camera inside the bag passes from one set of agents’ arms to another. Alas, the image wasn’t much—a black screen with no video at all—conveying a story to the world and a point of view that would in short order devastate the totalitarian regime.

FIGURE 1.2

When an undercover agent suddenly grabbed Piotr’s camera, no one thought about turning the camera off!

FIGURE 1.3

What’s this? A dark screen? If the context is right, you don’t need much to tell a compelling story!

FIGURE 1.4

In this pivotal scene from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), we listen to mostly unseen characters in a dark projection room. Suppressing visual content in this way forces an audience to listen, this strategy being very effective to communicate critical dialogue or exposition

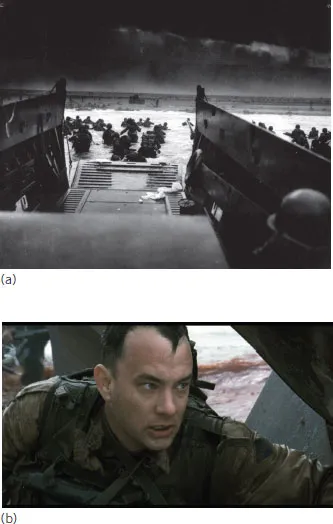

FIGURE 1.5 a,b

Conversely, we can force the viewer to focus more on the visual story by attenuating or eliminating the audio entirely. Managing the interplay of picture and sound is the essence of a filmmaker’s craft. (b) The muted audio in this scene from Saving Private Ryan (1998) reinforces the horror of the D-Day beach landing at Normandy.

FIGURE 1.6

Ninety percent of a video story is communicated visually. Given a choice, viewers always prefer to watch than to listen. They cannot do both at the same time!

FIGURE 1.7

Show me; don’t tell me! Great storytelling requires compelling visuals!

YOUR STORY’S POINT OF VIEW

I’m often asked, “Which camera should I buy?” and “Which camera is best?” These questions are loaded and often laced with fear. My answer is always the same: It’s the camera that best supports the point of view of the story you’ve chosen to tell.

There are always trade-offs in whatever camera you choose, and you should be leery of selecting a make or model based on a single feature such as imager size or resolution. High-resolution cameras may have associated drawbacks like inferior low-light response, constrained dynamic range, and a bevy of shuttering artifacts owing to their large CMOS 1 sensors. These compromises along with a data-intensive workflow can have a negative impact on your filmmaking efforts, so is the highest resolution camera really what you want or need to convey your visual story and the desired point of view?

If a close-focus capability is crucial for your documentary work, then a small compact camcorder with servo focus may be preferable to a full-size model with manual optics. Pricey broadcast lenses will almost always produce sharper, more professional images, but they cannot usually focus continuously to the front element owing to the limitations of their mechanical design.

There is no perfect camera for every application. Every model has its strengths and weaknesses, the compromises in each camera being more apparent at lower price points. If you really know your story and the intended point of view, you can select the right camera, which need not be the most expensive or sophisticated. Similar to a carpenter, a plumber, or an auto mechanic, the smart shooter understands his or her tools and how they may advance (or hinder) his or her goals as a craftsperson. 2

FIGURE 1.8

Shooting on a public pier without a permit? A consumer Canon HF-S100 or DSLR may be ideal. Shooting a documentary for The Discovery Channel about the mating habits of the banded mongoose? The full-size camcorder with variable frame rates and a smallish 2/3-inch sensor is perfect. Secretly capturing passenger confessions in the back of a Las Vegas taxi? The lipstick camera or even the Go Profits the bill. When it comes to gear, your story and intended point of view trump all other considerations!

NO MORE CHASING RAINBOWS

The notion of a shooter as a dedicated professional has been er...