- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As a student, and in any profession based on your studies, you need good oral communication skills. It is therefore extremely important to develop your ability to converse, to discuss, to argue persuasively, and to speak in public. Speaking for Yourself provides clear, straightforward advice that will help you:

- be a good listener

- express yourself clearly and persuasively

- contribute effectively to discussions

- prepare talks or presentations

- prepare effective visual aids

- deliver effective presentations

- perform well in interviews.

In short, it will help you to express your thoughts clearly and persuasively – helping to achieve your short and medium-term goals as a student and your career goals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Speaking for yourself

Good communication skills are needed in everyday life, in study at college or university, and in any career based on such studies. Yet, after more than twelve years at school, many students entering higher education are unable to express their thoughts clearly and effectively in their own language. They need to improve their writing and to develop their ability to converse, to discuss, to argue persuasively, and to speak in public. Indeed, employers complain that after a further three years in college or university, many students applying for employment still have poor communication skills.

Recognising that many school leavers need to improve their communication skills (and to develop other interpersonal skills needed for success in study and in any profession), all courses in further and higher education are intended to facilitate both learning and personal development (see Table 1.1). As a student, therefore, you will receive comments and advice on your written work to help you to improve your writing, and you will have opportunities to discuss your work and to give short talks or presentations. That is to say, you will be encouraged to develop your ability to express your thoughts effectively.

Most people probably take for granted their ability to speak, not thinking much about it until they have to address an audience or attend an important interview. But just as your first impressions of other people are based on how they look and how they speak – so are their impressions of you. Every time you speak, not just when giving a talk or being interviewed, you are both conveying information relevant to the subject being discussed and presenting yourself.

When you meet people for the first time their immediate feelings about you, based on your appearance and behaviour, are important both at the time and later – because they are not easily forgotten or revised. You never have a second opportunity to make a good first impression; and those people whom you meet only once may never have further evidence of your character and ability.

Table 1.1 Some skills needed in studying any subject and in any career*

Your appearance and speech may create barriers between you and the people you meet, or may help them to feel at ease in your presence. From your speech people make assumptions, which may or may not be correct, about your place of birth and social class (from your pronunciation), about your education (from whether or not you express your thoughts clearly), about your interests and opinions (from what you say), and about your intelligence (from whether or not what you say seems to make good sense).

When you speak, you know what you are thinking and how you feel about it; and as you speak other people make judgements about your character and assumptions about what you are thinking and why: first from your appearance, and then from how you speak and from what you say (see Figure 1.1). As people come to know you better they also judge you by what you do – by your actions, which speak louder than words: they make clear whether or not you meant what you said.

WORDS SPOKEN

EYE CONTACTS and FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

POSITION POSTURE GESTURES

INTEREST and AWARENESS

BACKGROUND and PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

FIXED OPINIONS and PREJUDICES

PREFERENCES and LOYALTIES

MOTIVES and HIDDEN AGENDAS

ATTITUDES and BELIEFS

PREOCCUPATIONS

UNDERSTANDING

THOUGHTS

INTEREST and AWARENESS

BACKGROUND and PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

FIXED OPINIONS and PREJUDICES

PREFERENCES and LOYALTIES

MOTIVES and HIDDEN AGENDAS

ATTITUDES and BELIEFS

PREOCCUPATIONS

UNDERSTANDING

THOUGHTS

Figure 1.1 Verbal and non-verbal communication; thoughts and feelings. There is much more to an iceberg than meets the eye of a seafarer. Similarly, our behaviour, which others perceive in face-to-face conversations, provides clues to what is below the surface: to our thoughts and feelings, and to why we are as we are.

How you speak

We are remarkably sensitive to the vocal characteristics of speech, as indicated by our ability to recognise the voices of many people whom we hear only in telephone conversations or on the radio. We also notice other characteristics of the way people speak. If they are considerate, in any serious conversation or discussion we expect brevity, clarity, sincerity and politeness. From such clues, when speaking on the telephone or listening to the radio, we may form an impression of a person’s character – which may or may not be correct. In face-to-face conversations we are more confident in our ability to judge people from the way they speak.

Be brief

Even if listeners are interested in what you are saying, they will expect you to come to the point quickly. In a presentation, ten minutes with one person talking is long enough. That is why experienced speakers, especially in longer talks, use facial expressions and gestures as well as words, and include visual aids, demonstrations, samples, specimens and handouts, as appropriate, and perhaps ask rhetorical questions, so that people do not have to sit and listen for more than a few minutes to just one person speaking.

Radio and television producers require a listener to have only a very short attention span. Many news programmes have two news readers or presenters, and neither they nor the other contributors speak for more than a few seconds at a time. Similarly, in everyday conversations and discussions most people speak briefly and to the point. All participants are stimulated by the variety of contributions and are likely to feel involved.

Be clear

Think before you speak

Clarity in a formal talk, presentation or speech, as in writing, depends on choosing words that both you and your audience understand (see chapter 4 Choosing the right word) and on expressing your thoughts in carefully considered and properly constructed sentences (see chapter 5 Using words effectively). In conversation it is not usually possible to achieve such clarity because, instead of thinking and planning before attempting to communicate, you have to think as you speak, and while others are speaking.

Conversation and discussion help to clarify your thoughts and contribute to your own knowledge and understanding of any subject, as does all the work that goes into your preparation of an essay or written report. So you are likely to be in a better position to talk or to write with clarity about the subject at the end of any conversation or discussion than you were at the beginning.

Know your subject

Before explaining things to others, you must ensure that you have sufficient knowledge and understanding yourself. Then you must consider how best to explain. As a result, conversation and discussion may be part of your preparations before you give a talk or presentation, as they are before you write an essay or report.

Use appropriate language

In higher education and in most careers, to be widely understood when speaking, as well as choosing words that they expect everyone present to understand, most people use standard English words and standard pronunciation (also called received pronunciation because it is widely understood). Those who use slang (highly colloquial language, including words that are not included in the vocabulary of most educated Englishspeaking people, and words used in a special sense different from their commonly accepted meaning) will not be so widely understood.

For example, unless you were born in north-east England, you might not understand every word of the anonymous tragic ballad about ‘The Lambton Worm’ (a dragon), especially if the singer had a strong Wearside accent. It begins:

Whisht lads, haad yer gobs

Aal tell ye aall an aafu’ story

Whisht lads, haad yer gobs,

Aal tell ye boot the warm.

This means, in standard English: ‘Quiet, everyone, while I tell you this story, full of awe, about the worm.’

If you use standard English (as used in quality English-language newspapers in the British Isles and elsewhere), choose words that convey your meaning accurately, arrange them in carefully constructed unambiguous sentences, and pronounce each word correctly (using standard English pronunciation, as explained in a good dictionary), you will be understood by English-speaking people everywhere.

Pronounce each word carefully

Whatever you are trying to achieve, you must articulate carefully and speak so that everyone present hears every word. On a formal occasion, as in an interview or when delivering a talk or presentation, it is best to use standard English; but if appropriate on a less formal occasion, as in everyday conversations and discussions, you may prefer to use a more colloquial language (see page). But clear articulation is always necessary, in addition to the clarity that results from care in the choice and use of words.

Be sincere

By convention a personal letter ends with the complimentary close ‘Yours sincerely’ or ‘Yours truly’, affirming that you believe what you have said to be true. In any serious conversation it should not be necessary to say that you are sincere; but for your words to carry conviction – in standard or colloquial English – your voice must sound sincere, and in face-to-face conversations or when addressing an audience you must look sincere.

Most people find it easiest to maintain eye contact when they are telling the truth, and may look away when they are not. However, a person’s sincerity cannot be assessed by eye contact alone, and a listener who has to cope with rather too much eye contact may suspect that a speaker is insincere – and trying too hard! Similarly, a person who is sincere does not gain credibility by using superfluous introductory phrases that indicate to listeners that the speaker does not always tell the truth (see Table 1.2).

There are of course many occasions when it is not possible to tell the truth, perhaps to avoid breaking a confidence or to avoid giving offence. Then it is important that one should not tell lies, because of the loss of confidence and credibility later when lies are detected. You may be able to avoid telling lies about other people by saying that you cannot answer for them: that you cannot affirm or deny any statement, or discuss any rumour concerning their affairs. Otherwise, as in the game ‘Twenty Questions’ (in which the answer to each question must be either yes or no), a questioner will soon obtain relevant facts by a process of elimination.

Table 1.2 Some introductory phrases to avoid

Be polite

The usual greeting when meeting someone for the first time is to say ‘How do you do’ or, less formally, ‘Hello’. Then, to end this first conversation, if appropriate you could say ‘It has been a pleasure to meet you.’ More important, you should look as if your meeting has been a pleasure.

When meeting someone whom you know well, a common greeting is ‘How are you?’. This greeting is not an invitation to recite your medical history or to provide an up-date on your state of health.

In any conversation, you are most likely to persuade others, or to obtain their agreement, co-operation and support, if you are obviously interested and considerate: (a) if your manner is friendly; (b) if you address individuals by name; (c) if you smile when you meet; (d) if you consult them at least on occasions when they should be consulted; and (e) if you agree with them when you can.

Special care is needed when you speak on the telephone, unless it is a video call, because there is no non-verbal communication. So, whatever else you say, always: (a) begin your conversation with your name; (b) use the name of the person you are calling; and (c) end, if appropriate, by saying ‘Thank you for your help’.

Etiquette, which may be taught as a set of rules, is a guide to acceptable behaviour in polite society – helping those in Rome to do as Romans do. Good manners in conversation, as in any other social interaction, are no more than common sense: showing one’s respect, interest and pleasure or, at least, ensuring that one does not give offence.

And certainly the greatest asset [one] can have is charm. And charm cannot exist without good manners – meaning by this, not so much manners that precisely follow particular rules, as manners that have been made smooth and polished by the continuous practice of kind impulses.Etiquette, Emily Post (1942)

Then tact depends not so much on saying the right things at the right time as on knowing what you should not say, including an awareness of topics that are best avoided.

When speaking, as with other aspects of behaviour, there are socially accepted notions as to what is and what is not appropriate in particular circumstances. For example, you might be expected: (a) to respond to a greeting with a similar greeting – and a smile; (b) to be co-operative, responding to a request either by agreeing to help or by explaining why you are unable to help; or (c) when asked ‘Would you like . . . ?’ to reply, with a smile, either ‘Yes please’ or ‘No thank you’.

In any conversation or discussion you must listen carefully to the contributions of others and have the confidence to contribute yourself. That is to say, you should listen without being submissive. Normally, you should be assertive, ensuring that your message is clearly expressed and understood (see Be forceful, page 39), but you should not be aggressive (for example, you should not attempt to dominate by speaking loudly or by using language intended to ridicule the views of others).

Abusive language, comprising words intended to offend the person addressed, is unacceptable – as are gestures intended to insult the person against whom they are directed. Such abuse, and the use of words or phrases that could give offence to anyone who differs from the speaker in age, appearance, race, religion or sexual orientation, are to be avoided in all conversations, discussions, talks or presentations – as a student and, after graduation, in any profession. Similarly, one should never say anything that is false or defamatory (scandalous) or anything likely to cause anyone to be shunned or avoided, or exposed to hatred, ridicule or contempt.

What is socially acceptable in conversation will depend on who is present, and on the place, the time and the occasion. Care is necessary not only in ensuring that your own conduct and use of words are appropriate but also in observing and interpreting non-verbal clues to the feelings of others. Even something as fundamental as a smile may be misunderstood by people whom you know well: it is not necessarily a spontaneous expression of pleasure; and laughter may indicate amusement, discomfort, embarrassment, surprise, wonder or . . . There are also cultural differences in expectations relating, for example, to the need for personal space and to the use or avoidance of eye contact (see BBC, 2005) which if not understood can easily cause discomfort or annoyance.

What you say

Be accurate

You may know the party game in which people sit in a circle, and one whispers a message to a neighbour, and then says ‘Pass it on’. All each person has to do is listen carefully and pass on the message. There would be nothing of interest in this game if each person listened carefully, remembered the message exactly, and whispered clearly – repeating it word for word. But usually this does not happen, and by the time the message comes round to the originator it is inaccurate and may have changed so much as to be amusing. The more people there are in the circle, the more it is likely to differ from the original.

In other situations, failure to pass on messages accurately is likely to have serious and even fatal consequences (for example, inaccurate messages may result in a waste of time in any business, in a loss of production in industry, or in a failure to respond appropriately when first aid is required urgently immediately after an accident). This game can therefore be used in courses on communication skills as the basis for a class exercise. It can also be used when training first aid workers, for example, to emphasise the care needed to ensure clarity and accuracy when passing messages by word of mouth.

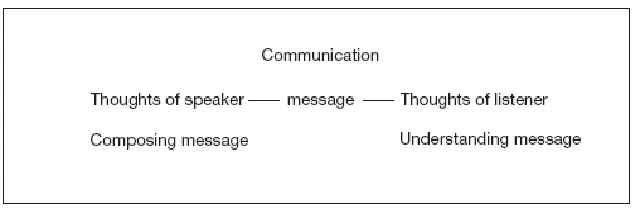

Communication is complex, even when speaking to someone directly, face to face or on the telephone, or when sending a written message. It is not easy to ensure that you have expressed your meaning adequately or that you will be understood (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Accurate communication, using words alone, is not easy. Verbal communication involves your choosing words and using them to convey your thoughts accurately as an unambiguous message – in an attempt to evoke identical thoughts in the minds of listeners or readers, so that they understand your message correctly.

In verbal communication (when transferring information using words alone, as in a letter or an e-mail, or when speaking on the telephone to someone you cannot see), you (the sender) put your thoughts into words so that they can be sent as a message – in an attempt to provoke identical thoughts in the mind of a reader or listener (the receiver). This involves care on the part of the sender, who must: (a) consider what the receiver needs to know and why this information is needed; (b) convey just this information as a message, with enough supporting detail; (c) choose words the receiver is expected to know and understand; and (d) use these words correctly in well-constructed unambiguous sentences.

Care is also necessary on the part of the receiver, who must pay attention both to the words used and, in speech especially, to the way they are expressed. Then the interpretation of the message is influenced by the receiver’s prior knowledge, likes and dislikes, opinions and beliefs, and in face-to-face conversations, discussions and talks, by the accompanying non-verbal signals.

Whether or not people are actually s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures and tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Speaking for yourself

- 2 Conversing

- 3 Discussing your work

- 4 Choosing the right word

- 5 Using words effectively

- 6 Preparing a talk or presentation

- 7 Preparing visual aids

- 8 Speaking to an audience

- 9 Finding information

- 10 Speaking in an interview

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Speaking for Yourself by Robert Barrass in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.