eBook - ePub

Congenital Heart Disease in Adults

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Congenital Heart Disease in Adults

About this book

This highly illustrated, well-written and beautifully produced text is aimed at cardiologists and internal medical doctors, whether qualified or in-training, who are not specialized in the field of congenital heart disease, who will, nevertheless, meet these patients more and more often in their daily practice. The complicated subject of congenital

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Congenital Heart Disease in Adults by Jana Popelova,Erwin Oechslin,Harald Kaemmerer,Martin G. St. John Sutton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Cardiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

History

Until the early 20th century, it was difficult, if not impossible, to establish the diagnosis of congenital heart disease (CHD) during a patient’s lifetime. As a result, CHD drew mostly the attention of pathological anatomists.1, 2 and 3 Remarkably, as late as 1934, only one of 62 cases of atrial septal defects demonstrated by autopsy was diagnosed during a patient’s lifetime.4

The first to describe an open arterial duct was the Greek physician Galenos in the 2nd century AD.5 In the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci recognized a patent foramen ovale. Tetralogy of Fallot, while actually described by the Danish anatomist and theologian Nicolas Steno as early as 1673, was not diagnosed in vivo until 1888, by Arthur Fallot, hence the term.6 In 1879, Henri Roger not only described the morphology but also the clinical features of a minor ventricular septal defect, consequently sometimes referred to as Roger’s disease.7

The 20th century witnessed a remarkable development of diagnostic methods followed, after World War II, by a turbulent development of cardiac surgery.

Diagnosis of congenital heart disease

Several imaging modalities are used to confirm CHD when it is suggested by the symptoms and physical examination. In previous years, diagnosis and treatment of congenital cardiac disease often depended on cardiac catheterization. In the past decades, however, the number of diagnostic catheterization procedures has steadily declined in favor of interventional procedures, and imaging methods have shifted toward the use of less invasive and noninvasive techniques. Echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized tomography (CT) have gained a well-established role in the morphological and functional assessment of the heart and the great vessels.8

Noninvasive echocardiography started in the 1970s–1980s. In the late 1980s, 80% of children were referred for surgery exclusively on the basis of noninvasive diagnosis, without catheterization. As adults are much more difficult to examine by ultrasound than children, transesophageal echocardiography, affording accurate diagnosis of CHD in adults, was another major step forward. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction, intravascular ultrasound and tissue velocity imaging may yield new insights into the anatomy and function of the heart.

MRI is extremely useful for delineation of the anatomy of the heart and great vessels, as well as for nonquantifiable assessment of blood-flow characteristics. The high resolution of this technique provides excellent spatial separation without limitations in the orientation of views. The development of specific techniques (fast gradient-echo, velocity mapping, echo planar imaging, myocardial tagging, and spectroscopy) allows quantification of physiological and pathological hemodynamic conditions. In particular, 3D-MRI reconstruction clearly demonstrates complex arrangements and clarifies morphology of complex CHD. Using MRI-fluoroscopy techniques, some centers have started to carry out balloon angioplasty of stenotic lesions, as well as radiofrequency ablation under MRI guidance.9 The late gadolinium enhancement technique provides assesment of the fibrosis and scarring of the myocard of the left or right ventricle. The clinical indications for MRI in adults with congenital cardiac disease are well established for the evaluation of anatomy and/or function. It is considered a gold standard for the evaluation of the systolic function of the right ventricle.

Several newer CT technologies (e.g. spiral and multislice CT, dual-source CT) are in use as minimally invasive procedures: the high resolution of the images provide excellent spatial separation. A CT angiography is an important examination before reoperation.

Unfortunately, neither MRI, nor CT, nor ultrasound can accurately define intraluminal pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance. Therefore, catheterization is currently the only way to measure systemic or pulmonary pressure and resistance.10

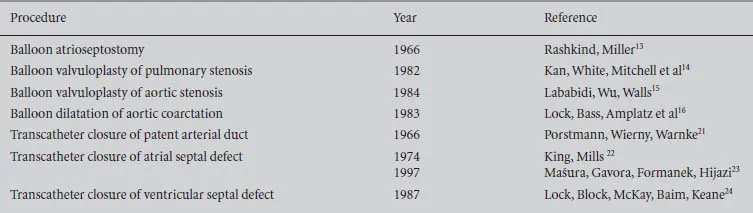

However, today, catheter-based methods are no longer used for diagnostic purposes only, and may replace certain cardiac surgical procedures in CHD.11, 12 Balloon atrioseptostomy in the critically ill newborn with uncorrected transposition of the great arteries was reported as early as 1966;13 balloon percutaneous valvuloplasty of pulmonary artery stenosis in 1982;14 and balloon valvuloplasty of aortic stenosis in 1984.15 Balloon angioplasty, possibly combined with stenting, can be used to manage aortic recoarctation, or even native aortic coarctation.16, 17, 18, 19 and 20

Table 1.1 First transcatheter procedures in congenital heart disease (CHD)

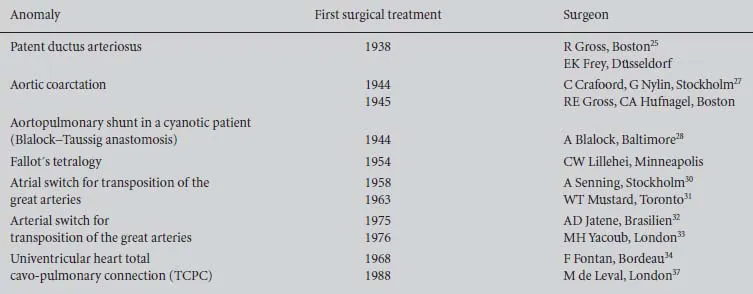

Table 1.2 Milestones in the history of surgery for congenital heart disease (CHD)

Closing a patent arterial duct was the first catheter-based closing procedure in CHD, performed by Porstmann in 1966.21 After the advent of technically more sophisticated devices, and detachable spirals in particular, interventional closure of patent arterial ducts has found even broader acceptance. It is not only adult patients with CHD who have benefited from the development of the interventional closure of an atrial septal defect or a patent foramen ovale. While the possibility of catheter-based closure of atrial septal defects was initially reported in 1974,22 the method has found a wide acceptance since the 1990s, when technically sophisticated occluders such as the Amplatzer septal occluder became available.23 The transcatheter closure of ventricular septal defect is used for muscular defects, and for some perimembranous ventricular septal defects.24

Cardiac surgery

The first successful ligation of an open arterial duct was undertaken in 1938 in the USA by Robert E Gross in Boston,25 and independently by Emil Karl Frey in Germany.26 The first surgery of coarctation of the aorta was performed by Clarence Crafoord from Stockholm, using Gross’s technique, in 1944.27 Palliative subclavian and pulmonary anastomosis in tetralogy of Fallot was first created by Alfred Blalock, as suggested by the pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig, in 1944.28 While the first to operate on an atrial septal defect on the closed heart was Sondergaard in 1950, an atrial septal defect was closed in the open heart using direct suture by Gross in 1952. Closure of a ventricular septal defect and correction of tetralogy of Fallot in the open heart and ‘on pump’ was pioneered by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 History

- 2 Prevalence of congenital heart disease in adulthood

- 3 Atrial septal defect

- 4 Patent foramen ovale

- 5 Atrioventricular septal defect

- 6 Ventricular septal defect

- 7 Tetralogy of Fallot

- 8 Coarctation of the aorta

- 9 Bicuspid aortic valve and diseases of the aorta

- 10 Pulmonary stenosis

- 11 Transposition of the great arteries

- 12 Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries

- 13 Patent ductus arteriosus

- 14 Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve

- 15 Functionally single ventricle, Fontan procedure – univentricular heart/circulation

- 16 Cyanotic congenital heart diseases in adulthood

- 17 Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect

- 18 Congenital coronary artery anomalies

- 19 Persistent left superior vena cava

- 20 Anomalous pulmonary venous connection

- 21 Psychosocial issues

- 22 Cardiac injury during surgery in childhood

- 23 Terminology remarks

- Index