eBook - ePub

Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics

Volume 3: Transportation Systems, Medical Ergonomics and Training

- 482 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics

Volume 3: Transportation Systems, Medical Ergonomics and Training

About this book

This book is the third in the series and describes some of the most recent advances and examines emerging problems in engineering psychology and cognitive ergonomics. It bridges the gap between the academic theoreticians, who are developing models of human performance, and practitioners in the industrial sector, responsible for the design, development and testing of new equipment and working practices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics by Don Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Aviation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

COCKPIT DESIGN ISSUES

1 Realising flie benefits of cognitive engineering in commercial aviation

R. Curtis Graeber and Randall J. Mumaw

Boeing Commercial Airplane Group, USA

Safety as a benefit

The knowledge and tools of engineering psychology and cognitive ergonomics may provide considerable help in solving one of commercial aviation’s most significant challenges, reducing the accident rate. Boeing’s most recent statistical summary of commercial jet aeroplane accidents for 1988-1997 again shows that investigative authorities have determined the flight crew to be the primary cause in 70% of all hull loss accidents. This percentage has been consistent for almost the past two decades. While the flight crew is the most obvious example of the human contribution to accidents, the percentage goes up when maintenance- and ATC related causes are considered. Although continuous improvement in equipment reliability will undoubtedly prevent some future accidents, its potential contribution to safety is negligible compared to that offered by improving the reliability of human performance.

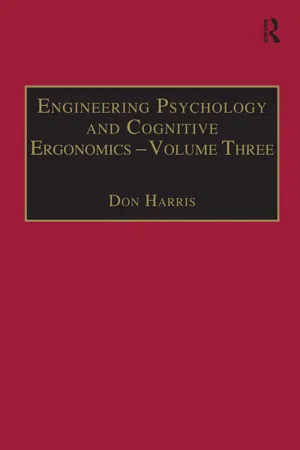

Improving flight safety is a goal expected by the flying public and shared by all aircraft manufacturers and operators. The history of commercial aviation demonstrates the industry’s success in achieving this goal with each new generation of aircraft. This progress is reflected in the hull loss accident rates for the world-wide commercial jet fleet, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 Hull loss accident rate by aeroplane type

The accident rate for recent designs, such as the B757, B767 and A31.0, are considerably better than the first-generation jet aircraft, such as the B707 and DO 8. Recently certified designs, such as the B777, A330 and A340, have not experienced in-service hull losses as of this writing, and are expected to demonstrate improved safety as a result of improvements in the systems safety design processes and more robust implementations of the designs. A major factor in this expected improvement is the commitment of the aircraft manufacturers to improved safety, together with improved certification regulations and continuing airworthiness programs from the regulatory authorities, including the United States Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) and the European Joint Airworthiness Authority (JAA).

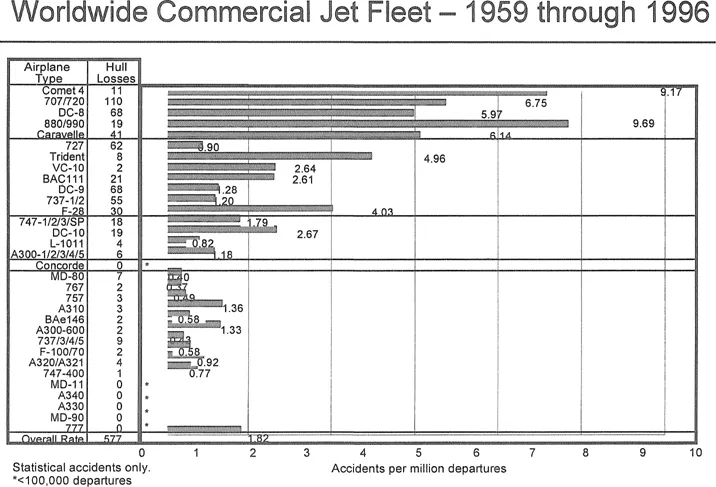

As shown in figure 2, world-wide air travel is expected to continue its expansion in the years ahead. Annual departures are predicted to increase from the current level of approximately 17,800,000 to 30,000,000 in 2015. This will be accomplished by an expected increase in the number of jet transport aeroplanes in senvice from about 12,500 today to about 23,000 by the end of this time period. If the accident rate were to be held constant at the current level of about one per million departures, the result could be a serious accident every one or two weeks in 2015. While this statistic would technically reflect a level of safety equivalent to today’s level, the public’s perception of safety in air travel is based to a large extent on the frequency of news reports rather than accident rate statistics. With the globalisation of the electronic media, every accident now has an impact well beyond local and national boundaries, no matter where it occurs. It affects all of us, not just the airline, the manufacturer, or the country directly associated with it. It is very clear that further reductions in the accident rate are required to prevent this more negative perception of aviation safety. At a minimum, a two-fold improvement is needed, but the goal should be greater, perhaps an improvement by as much as a factor of five, to ensure that the achieved results are acceptable.

Figure 2 Need to improve safety as a function

of increased risk exposure

of increased risk exposure

Taking a broad approach

There are many areas that offer potential for safety improvements in large commercial aeroplane operations. These include maintenance, air traffic management (ATM), infrastructure and changes in the design of aeroplanes themselves. Yet, if the past record is any guide, the greatest leverage for improvement resides in improving flight operations safety. This will not be easy, partly because the reduction will have come in the form of substantially fewer human ‘caused’ accidents. The vast majority of these accidents have their roots in human error and, more important, in human errors that could be avoided or mitigated if we better understood their origins. If we could all focus our efforts towards applying the findings and methods of engineering psychology and cognitive ergonomics to interface design and procedures (including training), for both flight crew and controllers, the safety gains would be substantial. For the purposes of this paper, we will hereafter refer to the application of engineering psychology and cognitive ergonomics as ‘cognitive engineering’.

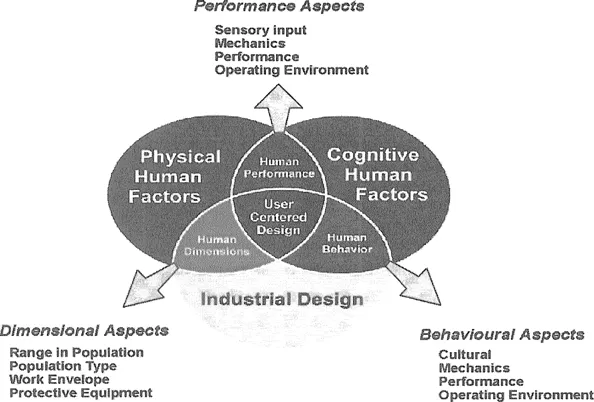

At Boeing, we continually follow scientific developments as well as technical developments to guide our work in this arena. The flight deck designs of our latest aeroplanes, the 777 and the Next-Generation 737 series, reflect these efforts. However, the Human Factors Engineering program at Boeing is not restricted to only flight deck issues and accident prevention. It is much broader and demonstrates the widespread influence that cognitive engineering can have on improving the ability of people to perform safely and effectively in the aviation industry. As figure 3 shows, we address human performance across a diverse set of functions and situations in an attempt to improve design, usability, maintainability, and reliability. In addition to flight deck issues, we are concerned with maintenance and the activities in the cabin, both in current aircraft and future designs. These efforts are carried out by a staff of over 35 graduate level professionals teamed with engineers, safety experts, and user representatives, i.e. test and training pilots, chief mechanics, etc. Thus, we are able to address human factors problems in a focused manner that brings scientific, engineering, and operational knowledge and tools to bear on issues affecting human performance.

Figure 3 An integrated approach to human factors

engineering and user-centred design

engineering and user-centred design

Human factors challenges to safe operations

The aviation industry does not stand still for long. Before describing some detailed examples of recent efforts using cognitive engineering to improve safety, let’s examine some of the emerging industry trends and dynamics that add new challenges to developing good aeroplane designs and operating them safely.

First, the jet aeroplane market has rapidly expanded, across the entire globe. Aeroplanes are being bought or leased and operated in parts of the world that, in other ways, are not technologically advanced and where there is a relative paucity of technical skills or workforce education. As a result, there is increasing pressure to take complex jobs, such as piloting or maintenance, and reduce their complexity. While task simplification is a hallmark of sound cognitive engineering, uninformed approaches to simplification can result in attempts to automate and proceduralise large elements of the job. That is, more of the burden of operations and maintenance is assumed by the designer, and some degree of authority is removed from the human. While some original error mechanisms may be eliminated, other types can arise. In particular, the human becomes more removed from the actions of the automation, and loses comprehensive awareness of the system’s current state and how it got there. If the automation fails to achieve its goal, the human is too often unable to diagnose the problem and recover from it. Thus, there is a price to be paid for trying to design for less technically competent individuals when the process of simplification can shut the human out. The irony is that humans are often still assigned blame when errors do occur.

Another implication of expanded global operations is that language skills are often insufficient for efficiently communicating operational or safety information in English. In some cases, a second language can be used, but in many cases communication is best done without words. Therefore, we need to rely more on pictures or graphics to communicate key information. This is particularly true for passenger safety information.

A second challenge is the economics that drive the industry. Commercial aviation is human resource intensive, and airlines experience strong pressures to reduce staff or reduce staff training as a way to reduce costs and increase profits. As in other industries, automation offers a tremendous opportunity to improve efficiency while reducing the number of more costly, better educated and more technologically savvy employees. Of course, the human performance risks are the same raised within the globalisation context. Again, humans become supervisors of automation, but their understanding of the systems they are supervising may be insufficient.

A third challenge derives from the culture of ‘blame’. Aviation has traditionally relied on selection, training, licensing, and detailed written procedures to assure safety. While these are important barriers to human error, this emphasis ignores the very real contributions of design, environment, and other factors to human performance. An over-reliance on discipline to make the system work well characterises many government authorities as well as air carriers. The phase ‘blame and train’ probably best describes the predominant attitude towards those who err and are caught. As a result human performance issues are often not given the level of analysis they deserve.

Yet, there has always been an implicit assumption that the trained pilot or mechanic can be counted on to remain sufficiently flexible and creative to fill in the gaps in the system to maintain safe performance. Given the often unpredictable nature of the aviation operating environment, there is no doubt that this uniquely human ability has been a major factor in making aviation as safe as it is today. So why are errors often blamed on negligence or incompetence without looking more broadly at the system and the way it supports human performance? Even when more serious incidents and accidents occur, it is rare to see a thorough human factors analysis conducted. If we as an industry are to make the human performance gains necessary for dramatic improvements in safety, we need more extensive and reliable feedback on how humans interact with our systems in the real world. We believe that the industry needs to foster further development of human factors tools, databases, and support policies across all sectors of the industry, not just for flight crews. Of course, the biggest challenge will not be technical but rather the political and legal frameworks needed to encourage honest reporting when human error is involved.

Finally, any attempt to address safety through improved design must take into account the size and composition of the current and futu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Part One: Cockpit Design Issues

- Part Two: Air Traffic Control

- Part Three: Aviation Psychology

- Part Four: Driver Behaviour

- Part Five: Medical Ergonomics

- Part Six: Training