![]()

CHAPTER

1

Texts, literacy and learning

Introduction

All readers of this book will have at least one thing in common with the author. At some point in our lives we were all taught to read and to write. This teaching may have come from a person, or persons, or it may have been the result of particular experiences or environments. Yet taught we were, none of us being so fortunate as to be born literate. This observation sounds so obvious as to be trite, but it repays some thought as a starting point for a consideration of the teaching and learning of literacy.

Because most people, and, by definition, all those reading this book, are fairly accomplished readers, we tend to think very little about the ways in which we learnt this process and the teaching that we received. If we are asked to remember a time when we could not read, most of us have great difficulty in doing so. Being able to read seems so natural to us now that our acquisition of it is taken for granted.

The picture is similar when we think about our learning to write. Many people, when asked to think back to a time when they had difficulty in writing, will only refer to such experiences as being aware that they were untidy writers, or being unable to spell a word. These are only part of the writing process, of course. The more important aspect – understanding the purpose of making, and being able to make, meaningful symbols which can be read back – is often, like reading, taken for granted. Yet at some point in our lives all of us were given lengthy lessons, often repeated many times, in reading and writing. We were taught to read and write. What memories do we have of this teaching?

When I first meet groups of students, at the beginning of their initial teacher training courses, I always make a point of asking them to write about their memories of their own first encounters with reading and writing. This usually causes them some difficulty, and it will often take a little while before they realise that I am serious enough about the task for them to have to produce something. The written accounts that result from this task are then used as a starting point for a discussion about fundamentals in the learning of literacy. Remarkably, most accounts have a great deal in common with one another. Some concentrate upon early experiences of reading and two typical examples are given here:

I don't remember much about reading in the infants’ school. I think we used Peter and Jane. I remember getting very excited when I brought my first book home from the library. It was the story of Peter Rabbit and my mum had already read it to me at home. I insisted on reading it to Mum, Dad and my older brother that night before I would go to bed. I've still got a copy of that book, although the original fell apart through being read so much.

I learnt to read by reading the instructions for my Meccano set. I wanted to build a crane and there was nobody to help me. I remember struggling with the instruction booklet until I managed to figure it out.

Other accounts concentrate upon writing, and again, two typical examples are given:

I wrote a book when I was six. It was all about dinosaurs. We had been watching a television series at school and after each programme we had to copy out some notes from the blackboard. I decided to write about the programmes in my own words at home. My mother still has the book although it's a bit dog-eared now.

We used to write stories at school. I liked to write about ghosts and monsters. I remember my teacher telling me that one of my stories was ‘really gruesome’ and I pretended to know what she meant. I got my Mum to help me find that word in the dictionary when I got home and the next day I told the teacher I was going to write another ‘gruesome’ story.

It is very noticeable from these accounts that what these students tend to remember seems not to be the experience of learning to read and write but rather the particular texts which they read or wrote. This anecdotal evidence of the influence of texts upon literate and protoliterate people fits with an increased recent emphasis upon the importance of text itself in the development of literacy. Until fairly recently, somewhat surprisingly, text, the essential material of literacy, had been rather neglected in research into, and developments in, literacy teaching. While it has become a focus of attention in the last few years, in the process several tensions have emerged which have caused debate among practitioners and researchers alike. Text is back on the agenda but in a fairly controversial way.

The literacy triangle

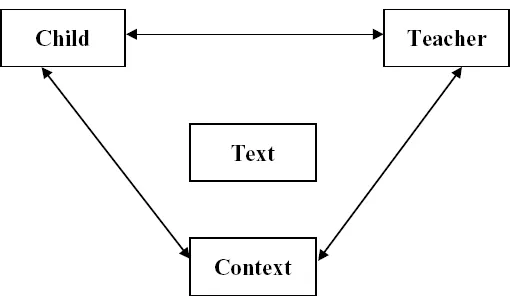

A model of the factors important in literacy teaching might be represented as a triangle with text at its centre (Figure 1.1). According to this model, basically, the teacher teaches the child to read and write in a particular instructional, usually classroom, context and using particular texts.

Our understandings about each of the parts of this model are now substantial. I will outline them briefly here.

The child as language learner and user

We now know a good deal about what reading and writing actually involve for the child and this emphasis upon the processes of literacy is in itself a significant shift from a previous concentration upon the products of reading and writing. We have learnt that the processes of reading and writing are complex and multi-dimensional and that they are influenced by, and to some extent depend upon, the purposes for which they are carried out. We also know that in learning these processes, children work out their own rules for how things work, progressively refining these in the light of wider and wider experience. This realisation of the active role of the learner in the learning has taught us the importance of examining the perceptions children have about these processes and purposes of reading and writing (Medwell 1990; Wray 1994).

FIGURE 1.1 The literacy triangle

The role of the teacher

The role of the teacher has come under considerable scrutiny and it is possible to discern at least two distinct trends in thinking about this role. On the one hand, during the latter part of the twentieth century, there was a discernible shift in emphasis from foregrounding the teacher as an instructor to widening the role to include teacher as facilitator, teacher as audience, teacher as model and teacher as co-participant. This shift coincided with a reconception of the learning process as a social construction of knowledge, rather than the traditional transmission/reception of knowledge model. The upshot of this change was that more stress began to be placed upon teaching as providing appropriate conditions for learning (Cambourne 1988; Wray et al. 1989).

More recently, we have also seen a renewed emphasis upon the role of the teacher as instructor and have begun to understand the crucial characteristics of effective teaching and effective teachers of literacy (Wray et al. 2002) and to realise that effective teaching of literacy is always concerned not just with the content of what is being taught but also the context in which that content is set.

Contexts for learning

A great deal of emphasis has been placed upon contexts for learning, in the sense of the environments in which learning is set. Stress has been placed upon the provision of demonstrations of literacy, upon the creation of atmospheres in which children feel safe to learn through experimentation and in which they get regular practice of using literacy for real purposes, and upon the careful structuring of support for children (‘scaffolding’ in Bruner's terms) as they ‘emerge into literacy’. The features of this environment for learning were summed up as ‘conditions for learning’ (Cambourne 1988), and such was the power of these ideas that it occasionally seemed that all teachers needed to do was to create a suitable context wherein children would ‘just learn’. The reality is, of course, that the business of teaching is not so simple and it is likely that a suitable context is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the efficient learning of literacy. In any case, it is beginning to become apparent that appropriate contexts are not as easily created as that, or as unproblematic. If context is perceived as subjective rather than objective reality, as the work of Edwards and Mercer (1987) and Medwell (1991) suggest, then there will be as many contexts in each classroom as there are children. Creating contexts will be dependent upon the individual perceptions of the participants in those contexts, which complicates the issue greatly.

The central role of text

In the past there was a tendency to under-estimate the importance of the texts which are created and recreated in the process of becoming literate. Texts were often thought of as simple servants of other pedagogic priorities. This can be seen clearly in the changing nature of the texts produced for early readers. These have been written for a number of purposes:

• To teach phonic rules. This approach produced phonically regular texts, and texts were graded according to the supposed complexity of the phonic rules they exemplified. Extreme versions of this principle produced texts such as ‘Can Dan fan Nan?’, but there were other reading programmes, such as Joyce Morris's Language in Action (Morris 1984), in which phonic regularity was handled much more sensitively and authors managed to produce some quite readable early texts.

• To teach specific words. This produced limited vocabulary texts where words were repeated so often that children could hardly help but become increasingly familiar with them. Such limitation, of course, makes the production of meaningful text quite a tall order and, again, extreme versions of this kind of text are now thought of as laughable: ‘Oh, oh, oh. Look, Jane. Look, look, look’. A great many reading programmes, however, including such very popular schemes as Oxford Reading Tree, use versions of this principle as one of their bases for producing texts.

• To stress predictability in reading. This produced texts in which repetition was at the level of the phrase or sentence rather than the word. Once a child had read one page of such a text, it required little fresh learning to read the following pages. Texts such as ‘Along came a crab, a big blue crab. “Ho ho,” said the octopus, “come and play with me.” “Oh no,” cried the blue crab, “you'll eat me for your tea.” Along came a squid, a juicy, green squid. “Ho ho,” said the octopus … ‘[etc.] (The Greedy Grey Octopus, Tadpole Books) were designed to actively encourage predictive reading. Many modern reading programmes include texts which are similar to this in design.

• To be decodable. A decodable text is defined as containing a large proportion of words that could be expected to be decoded (pronounced) based on the phonics lessons already taught to a child. This concept has recently become important (and controversial) in the debate about teaching reading in the USA, where the governing bodies of both of the largest states, Texas and California, changed their requirements in the late 1990s for the reading programmes they were willing to support. Where previously they had supported only reading programmes which included authentic literature and predictable texts, they now insisted that 80 per cent (in Texas) or 75 per cent (in California) of the texts used with beginning readers should be decodable. Decodable texts have much in common with the previously mentioned phonically regular texts, and may include some equally meaningless passages. It is important to note, however, that their envisaged role in the teaching of reading is different. While the early phonically regular texts were envisaged as themselves accomplishing a good deal of the teaching of early reading, decodable texts are designed to be used after the phonics teaching has taken place as a means of giving children the opportunity to apply what they have learnt.

Such views of text as a means to an end can be contrasted with views of text itself as central to the process of becoming literate. Children read and write texts, teachers teach reading and writing with and through texts, and texts provide a context for understanding, creating and responding to themselves and other texts. Modern literary theory lays great stress upon the idea that texts are never autonomous entities but are rather ‘intertextual constructs: sequences which have meaning in relation to other texts which they take up, cite, parody, refute, or generally transform’ (Culler 1981: 38). It would be possible to conceive of literacy learning as being simply a matter of a progressive elaboration of textual and intertextual experience.

Attention to the nature and importance of text in its own right has stemmed from two quite distinct directions of interest which have, at times, seemed contradictory in their implications. One of these directions might be termed structuralist as it has involved the close analysis of the structure of texts, from a linguistic perspective, largely inspired by the work of Michael Halliday. Chapman (1983a, 1987), drawing upon the framework ...