- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

About this book

First Published in 1987. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ARTICLES

MAPS FOR THE METROPOLIS: A POSSIBLE GUIDE TO THE PRESENT

IAIN CHAMBERS

Aron said, pointing to his glass: ‘You see, my dear fellow, if you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy of it!’ Sartre turned pale with emotion at this. Here was just the thing he had been looking to achieve for years.1

Writing isn’t to do with signifying, but with surveying, mapping— even of worlds yet to come.2

Velo-city

The French critic Paul Virilio has suggested that the cities of the future will be airports: transit points connecting the movement of millions in flight between one megasuburb and another.3 That future, of course, has already arrived, and in the most appropriate location: in Texas, midway between Fort Worth and Dallas. The city of J.R.Ewing and amber-glass skyscrapers tested to withstand tornado winds of 150 miles an hour opened its international airport in 1978; a year later it was the third busiest in the world. This back-projection of the future is the world of postmodernism, where everything is ‘larger than life’, where the referents are swept away by the signs, where the artificial is more ‘real’ than the real, where Dallas is Dallas; where the world is first doubled and then dislocated.

The modern airport, with its shopping malls, restaurants, phones, post office, video games, bars and television chairs, banks and security guards, is a miniaturized city, a simulated metropolis: a metaphor of cosmopolitan existence where the pleasure of travel is not only to arrive, but also not to be in any particular place: to be simultaneously everywhere.

It is a condition typical not only of the contemporary traveller, but also of many a contemporary intellectual. Viewed from 35,000 feet, the world becomes a map. Recently some of the views brought back from high flying have arrived at the conclusion that the world is indeed a map. At that height it is possible to draw connections over great distances, ignoring local obstacles and conditions. At that height certain commonsense objections (‘down-to-earth’ views) to a reading of the terrain can be ignored. When further height is gained, the flight plan only needs to consider the relation between the plane (undergoing rapid metamorphosis into a spaceship at this point) and the flat referent beneath its fuselage. At this point, the meanings of events elsewhere are incapable of penetrating the space we have put between ourselves and them. Meaning contracts into the pressurized cabin. Life inside the plane, with the observations it affords, becomes more ‘real’ than the ‘reality’ we presume to observe. Knowledge of the social, political and cultural globe becomes the knowledge of a second-order reality, a ‘simulacrum’.

Flight: to fly, but also to flee. For there also remain more stubborn referents— material, sometimes even geological—that periodically pierce the daily networks of sense: violence, riots, strikes, war, earthquakes, famine, volcanoes, radiation, death. Temporarily connected to the media, the adjectives these events generate hang in the air, symptoms of vital connections: fear, hope, anger, joy, sadness, jubilation, despair. Close up, the world acquires alarming details, a startling complexity.

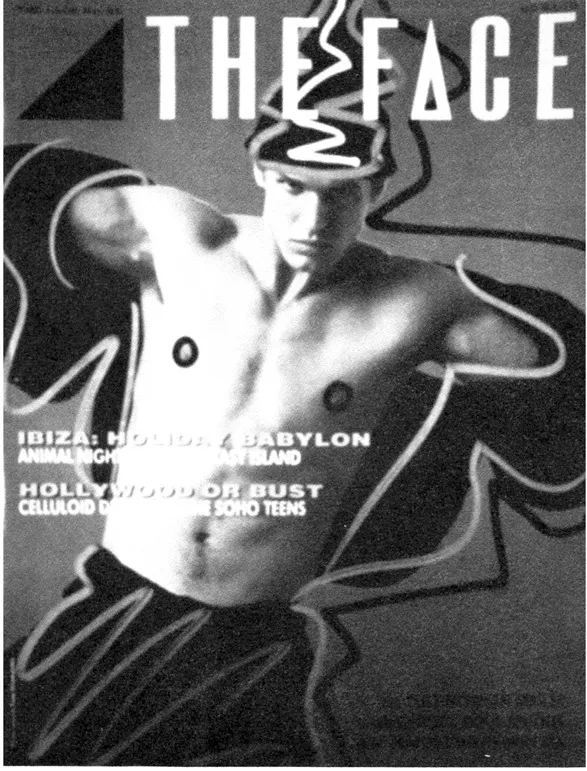

Meanwhile, between these terrestrial and extraterrestrial co-ordinates, we invariably find ourselves in the immediacy of the contemporary city, inhabiting commercial soundscapes and visualscapes that we personalize, customize and make our own. Here is a world where adverts quote videoclips and videoclips are adverts…or…are they art? It is a world in which Robert Elms, hip pop pundit and prophet of the fashionable metropolitan youth magazine, The Face, can inform the readership of the Sunday Times that ‘nobody is a teenager any more because everybody is’.4 In the face of fashion we are all stripped of our histories and turned into ‘absolute beginners’.

The idea of ‘revival’, so central to the cyclical novelty of clothing and contemporary imagery, has nothing to do with history. A revival does not set out to rediscover or faithfully quote a historical moment; rather, it revisits, recycles, re-presents a particular look, a sartorial gesture that has become part of the timeless wardrobe of contemporary mythology. Fashion is ultimately an abstract art. The German sociologist Georg Simmel noted in 1895 that fashion eschews the utilitarian laws of practical clothing for the daring translation of the fragile aesthetics of the novel into a temporary tendency, a style.5 Hence its fatal fascination: the genesis of fashion rests on rapid decay and precocious death.

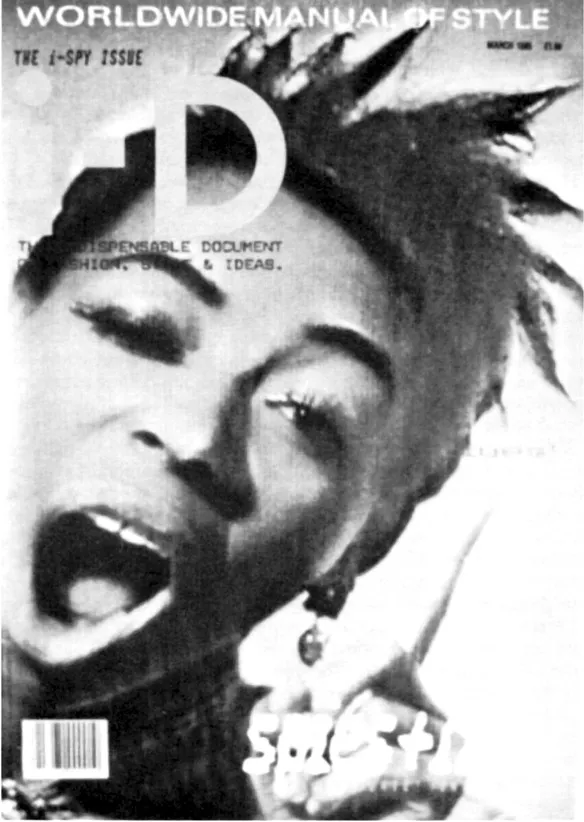

In this apparently rootless world, where accelerating signifiers refuse to slow down and be interpreted, we experience the semiotic blur and limitless crossreferencing of a vast urban catalogue. When Harrods department store in London recently opened a new boutique—‘The Way In’—and advertised it in the magazine i-D (the ‘Worldwide Manual of Style’), the caption consisted of a quote from Roland Barthes on the ontology of the photographic image.

Among these signs and sensations, contemporary popular culture (music, fashion, television, videos, drinking, dancing, clubbing) forms part of a language that provides the architecture of our daily lives and yet is without any apparent purpose. It is a language that exists beyond the obvious pragmatics of the sign; it carries its referents within itself, and encourages the vertiginous experience of the pleasure-in-itself.

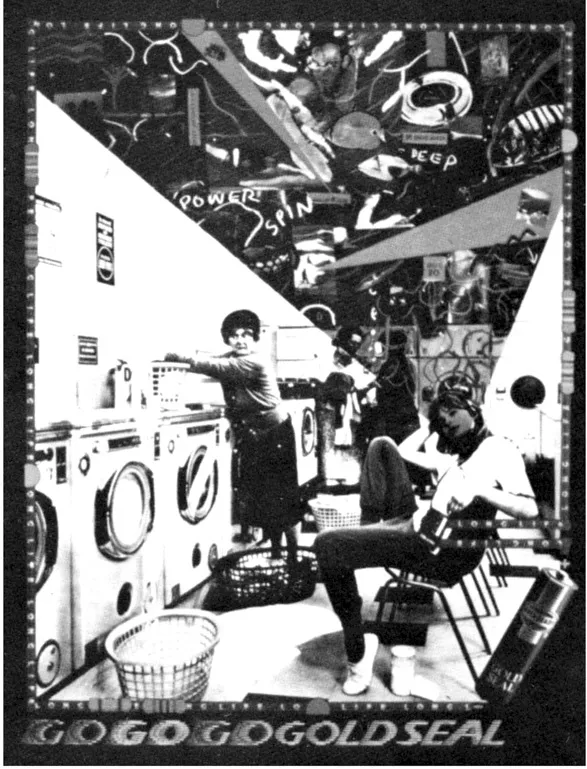

However, if we put some critical distance between ourselves and these immediate experiences of the everyday world (the metaphor of the plane returns), then all this can be viewed from another perspective. This language, this culture, these images, these sounds, have a brutal purpose: to make money and reproduce the situations that permit that exercise. And today we have arrived at such a level of cultural commodification that the duplicity of the sign, i.e. that the product might actually ‘mean’ something, can be done away with. Capitalism, commodification and culture have become one. The ‘spectacle’ of consumerism, to use Jean Baudrillard’s words, has been replaced by the ‘obscenity’ of an ‘excessive transparency’.6 Contemporary popular culture is merely a seductive sign-play that has arrived at the final referent: the black hole of meaninglessness.

Well, this gives us two views. One is brought back from a height where the air is thin and a distanced, synthetic view is permitted (synthesis (a whole, a totality)=synthetic (artifice, falseness)). The other comes from the altogether more messy and immediate prospects of life on the ground, where an excess of sense, sensations and signs overflows previous limits (intellectual, philosophical, aesthetic, social, political) in a barely recognized complexity. Flying, in more senses than one, is a ‘trip’, involving a shift in both geographical and existential co-ordinates; we go to an ‘other’ place, but eventually we also go home. The journey acquires its final shape and sense only once we have returned to the familiar textures of our world.

But I also want to argue that these intellectual flights, such as the journey into the theoretical stratosphere of postmodernism, are important. They provide the possibility for reorientating ourselves, the possibility of recognizing new landmarks and new lines that have been drawn across the map of the contemporary world. A critical intelligence adequate to the fluid complexity of the present is forced to fly regularly. But the importance of such a privileged observation (intellectual, philosophical, aesthetical) is realized only when the global is linked back to the local, when extensive tendencies are embodied in immediate trajectories, when perspectives become tangible projects, when a freedom of vision is translated into a democratization of everyday life.

In the rest of this article I shall try to indicate some of the spaces and fruitful tensions between these two views, between the perspectives of postmodernism and the prospects of popular culture, largely using pop music and its immediate cultures as my guide. I am interested in seeing not only how each plays off the other, but also how postmodernism, whatever form its own intellectualizing might take, has been fundamentally anticipated in the metropolitan cultures of the last twenty years: among the electronic signifiers of cinema, television and video, in recording studios and record players, in fashion and youth styles, in all those sounds, images and diverse histories that are daily mixed, recycled and ‘scratched’ together on that giant screen which is the contemporary city.

This is also to propose a further consequence: that contemporary intellectual work requires not prophets but the more modest labour of ‘cultural operators’. Some seek to ‘resolve’ the world, to explain it away: perhaps it is more significant simply to try to point in certain directions, to suggest certain connections that can be made in the slipstream of a world whose complexity has first to be appreciated if it is going to be better inhabited. So, if postmodernism presumes to provide a shooting script for interpreting the spectacle of the contemporary world, let’s try following it on the ground and run its perspectives across the grain of local details, where we can hear the voices of historical subjects making sense of their conditions, exploring their present, constructing a sense of the possible within the limits (and potentials) of their lives.

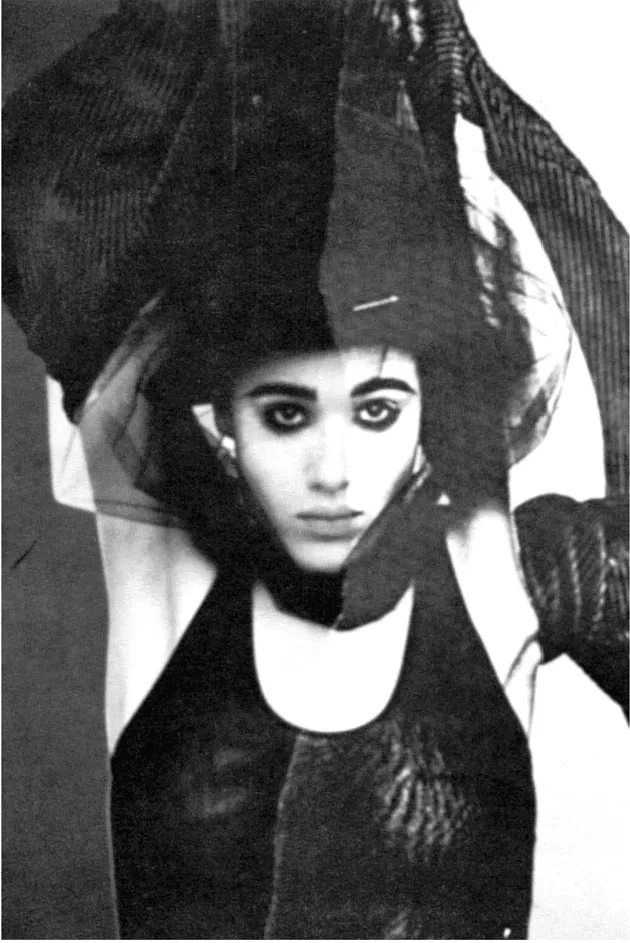

The look

In Britain, the fashioning of musics into local sense has frequently taken place through the public spectacle of youth and subcultural styles. These confront us with a complex sign-play. Over the surfaces of urban commercial culture they have affected what Dick Hebdige has recently characterized as the ‘theology of the look’, the world of the conditional tense, the ‘as if…’ world of advertising. It is a world at one remove from daily routines, where our clothes, our bodies, our faces become quotations drawn from the other, imaginary, side of life: from fashion, the cinema, advertising and the infinite suggestions of metropolitan iconography.

Let’s take these signs at face value rather than pretend to unveil a ‘truth’, as though they were merely masks. Perhaps the truth lies in the spaces between the signs, in the multiple interfaces that co-ordinate their movement.

In one sense, all British subcultures have represented stylistic replies to the question of class; a way of responding to one’s social condition at the level of the imaginary. But we could add that they therefore also represent a cultural ‘exile’, an attempt to go beyond the immediacy of class referents and their obvious social contexts. To imitate the slouch of a Hollywood gangster or the pout of his girlfriend was temporarily to extract yourself from the dead weight of your own past. Through the play of style and a sophisticated semiology of goods, subcultures and youth styles in general have tended to separate the idea of social imagery from the world of daily labour and an obvious class position, in the process adding a further dimension to immediate realities.

But things have changed since the heyday of teddy boys, mods and rockers. Other stories have emerged, further margins and more malleable styles have been revealed. The centrality of subcultures to the arguments of exclusion, urban romanticism and stylistic contestation has been displaced and dispersed.

In the second half of the 1970s, punk presented us with the breakdown of the image and the dispersal of obvious referents. As the last of historical male subcultures, the summation of previous spectacular styles, punk offered a subculture constructed on the crisis between sign and sense, between culture and class, between style and social situation; its own iconography was perversely constructed on the crisis of the very idea of subculture. The very signs of class, crisis, subculture and sex were ironically re-presented and recycled. But, while this bricolage of popular icons owed something to the New York art world example of Andy Warhol and The Factory, the sign-play here folded in upon itself and swapped a wider sense for a more secluded semantics. Indebted, at least in spirit, to French Dadaist and Situationist leanings (those slogans daubed across the clothes, those ‘situations’: puking in airport lounges, swearing on television and subsequently hitting the headlines), the codes of punk communicated the choice of avoiding an obvious sense or ready comprehension. Previous subcultures were dragged out of the closet and irreverently thrown into the window of style. There they were mixed up and perversely confused, without any respect for their earlier sense. The same discourse applied to the music. Like all subcultural music, it was the rude messenger of cultural insolence; but this time around it was also the self-conscious sum of all previous rebellious sounds: the white noise of sonorial anarchy.

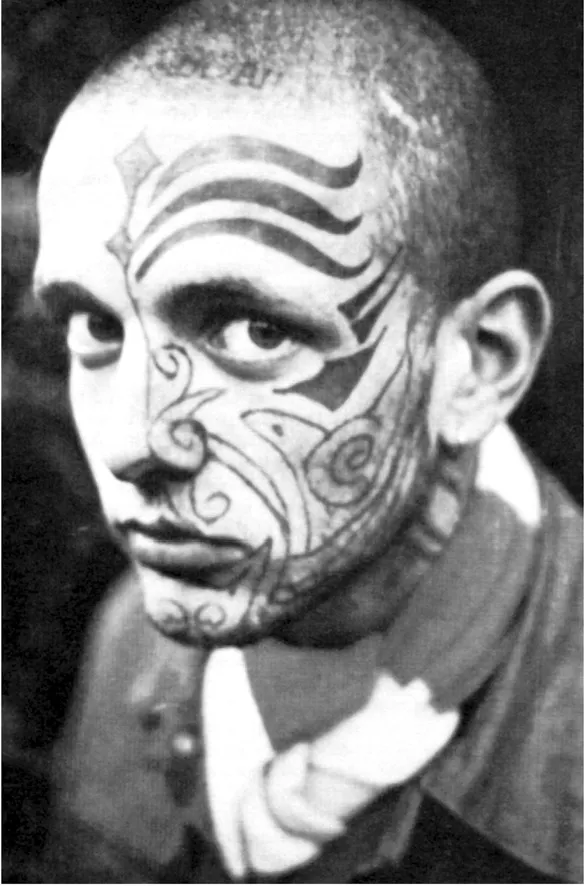

With punk—a subculture made up of the bits and pieces of previous subcultural worlds, earlier local totalities—we seemingly stand on the threshold of a new history, that of post-subcultural styles. The firm referents that guided the teddy boys or the mods in their stylistic options in music and clothes are apparently no longer available. Only the skinhead—recalling a mythically ‘authentic’ reality: the hard, masculine world of the proletariat that is mirrored in his braces, boots, shaved head and tattoos—remains as a stubborn referent, a symbol of the simple, timeless truths, those of the nation, of race, of patriarchy, of class.

Elsewhere, it is collage dressing and musical eclecticism that has dominated the 1980s. Where subcultures once offered a ‘strong’ sense of singular opposition to the status quo, this has now been replaced by a ‘weak’ sense of detailed differences; the ‘Other’ becomes simply the ‘others’.

So, in the epoch of the ‘post-’, even subcultures take their place in the museum of fixed symbolic structures. Involved in metropolitan languages that intersect on the surfaces of the everyday, in London as in Los Angeles, in Naples as in New York, previous rules give way to the flexibility of a collage, to the less traditional, less historicized, hence ‘lighter’ and more open, prospects of mixing the already seen, the already worn, the already played, the already heard.

Bodies

Our bodies—dressed, undressed, disguised, accentuated, in movement, in pose— provide another temporary map on which to observe how the signs and histories of style, social position, sexuality and race traverse a surface in common. The body is, in fact, central to pop’s semantic universe (and to contemporary urban culture in general). Around, across and through the body the social, cultural and sexual sense of pop music is most intensely organized.

It is above all in the voice, in dance, and in the sartorial regimes that orbit around its sounds that pop music encounters the socialized intimacy of the body. Here there is a public space, elsewhere rarely so easily available, where a whole series of choices—stylistic, sexual and social—are entertained.

All these choices are invariably still dominated by the male principle. Innovations have inva...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Articles

- Kites and Reviews

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies by James Donald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.