- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Musculoskeletal Radiology

About this book

Musculoskeletal Radiology is a single-source guide encompassing all of musculoskeletal imaging, examining classical diseases, as well as modern interpretations of disease. In-depth coverage of MRI and uses a basic "hands on"' approach to MRI for exploring the knee, shoulder, wrist, elbow, ankle, and foot.Other topics include:additional chapters on

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Musculoskeletal Radiology by Harry Griffiths in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Trauma

TRAUMA

Although many people have attempted to classify fractures, I believe that this is unnecessary, except perhaps in the ankle, where the mechanism of the injury is important for us to understand the fracture pattern. Elsewhere, we should simply describe the fracture. For example, is it transverse, vertical, spiral, or oblique? Is it comminuted or not (so-called simple)? Does it involve the joint, i.e., is it intra-articular? The question of it being compound (i.e., connects to the outside world) or not is usually a clinical and not a radiological one. If it is comminuted, we should describe any large, triangular fragments, which are known as butterfly fragments. In fact, most fractures are comminuted and are either oblique or spiral. Most fractures near the ends of long bones are intra-articular and thus more difficult to manage and treat. But that does not mean that you do not have to specifically look for that finding.

There are some basic rules: First, always take the proximal body part as being in the correct anatomical position, and refer the position and angulation of the distal body part to the proximal part, i.e., describe fractures of the foot with relation to the ankle and the proximal tibia to the distal femur or knee joint. Secondly, there is a concept of a “ring of bone” where, if one bone of a pair or one part of a ring gets fractured, then the other either fractures or subluxes. The pelvis is also a ring of bone, so always look for more than one fracture. The classical example of the former is the radius and ulna and the tibia and fibula. These will all be discussed in the appropriate subsections later in the chapter.

If there is a dislocation, look for concomitant fractures and describe the distal dislocated bone with respect to its anatomic relationship to the proximal undislocated side of the joint. For example, in anterior dislocations of the shoulder, the humeral head lies anterior to the glenoid. And, in anterior dislocations of the tibiotalar joint, the foot lies anterior to the distal tibia.

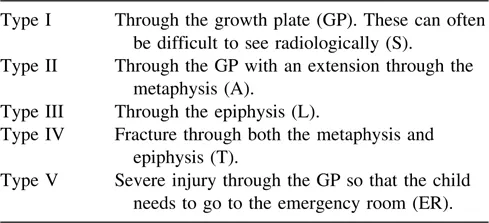

Other types of fractures occur, particularly in children, where we can see greenstick and torus fractures as well as fractures of the growth plate (Salter fractures). Once again, all of these will be discussed later in this chapter. Athletes get what are known as avulsion fractures where, for instance, the olecranon is avulsed off the proximal ulna by the pull of the triceps tendon, or the ischial tuberosity is avulsed off the ischium by the pull of the hamstring muscles. Salter fractures are classified depending on where the fracture line runs.

So what does SALTER spell ??? This is an easy way to remember the classification.

Stress and insufficiency fractures also need to be considered in athletes for the former and in patients with osteopenia for the latter. Pseudofractures can be seen in rickets and hyperparathyroidism, mainly secondary to renal failure. Incremental fractures are seen in those metabolic diseases that cause bowing of long bones, such as Paget’s disease and fibrous dysplasia. Pathological fractures are seen in association with any form of weakness in the bone, typically in association with metastases, primary bone tumors, and infections.

The complications of fractures also need to be considered. The acute complications include pneumothorax seen with rib fractures, arterial damage in comminuted proximal tibial fractures, or urethral damage in fractures around the symphysis pubis. Late complications include nonunion, avascular necrosis and infections. Each of these complications needs to be looked for as the fracture is healing.

Finally, although many of these findings can be seen on plain films, sometimes it is necessary to use computed tomography (CT) scanning or radionuclide bone scans to confirm the presence of a fracture or the configuration of fracture fragments. For example, CT scanning is essential in all complex pelvic fractures and in most shoulder girdle fractures. Bone scanning is useful in suspected sacral fractures as well as in stress fractures, although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is just as sensitive, but more specific.

A brief description of fracture healing is also useful so that the radiologist will know what to expect. Classically, there are three phases of healing: the inflammatory phase (usually 1–3 weeks), the reparative phase (3–8 weeks), and the remodeling phase (8 weeks onward). Healing obviously takes longer in older people than in the young, longer in large bones than in small ones, and longer in major fractures than in minor ones. Radiologically, the first signs of healing are the resorption of bone around the fracture site (i.e., increasing lucency and bone resorption). This is then followed by new bone formation, both periosteal and endosteal.

Once remodeling has started, the healing process can be clearly followed by radiographs. The late complications such as infection, nonunion, and avascular necrosis become obvious over time, but must be considered, particularly in association with specific fractures, i.e., nonunion of the tibia, avascular necrosis of the proximal pole of the scaphoid, and avascular necrosis of the femoral head in transcervical fractures of the femoral neck. Following fractures of weight-bearing bones, disuse osteoporosis is inevitable, becoming obvious by four weeks and usually reaching a peak by three months. Disuse osteoporosis is more unusual in fractures of the upper extremity, although it can be seen in elderly patients with distal radial fractures. A fairly common complication of fractures must also be looked for, and that is what appears to be delayed disuse osteoporosis. This is a specific syndrome known as Sudek’s atrophy or, more correctly now, as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, which starts at three months and reaches a peak at about one year. This will be discussed later. Finally, the management of fractures with internal fixation will be briefly discussed in chapter 7.

Nonunion of a fracture can be a difficult diagnosis to make, since one of the stages of healing is fibrous union. So, how can a radiologist make a competent, confident diagnosis of nonunion: only if both ends of the fractured bone develop sclerotic margins and especially if motion can be seen through the fracture site. Most radiologists will use the term “delayed union” rather than nonunion if they are not completely sure of the diagnosis. More recently, MRI has been used to determine if solid fibrous tissue has occurred across the fracture site or not, and this might be the way to go in the future.

SHOULDER

The Shoulder Girdle

The shoulder girdle consists of three bones and two joints: the scapula, the clavicle, and the proximal humerus, as well as the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints. Most fractures of the clavicle occur either in the midshaft or the distal end, mainly because the coracoclavicular ligament is fan shaped and is rather strong, so the fractures occur at either side of this (Fig. 1A, B).

There is an old orthopedic aphorism that states that fractures of the clavicle will reunite if they are in the same room. However, this is not entirely true, and occasionally one can see a nonunion, probably as a result of a soft-tissue interposition.

Figure 1 (A) There is a midshaft fracture of the clavicle with some angulation. (B) There is a fracture of the distal clavicle with evidence of motion.

Figure 2 (A) There is a grade III acromioclavicular joint separation (arrow). (B) There is a grade III acromioclavicular joint separation.

There are three grades of separation of the acromioclavicular joint: grade I, with a 50% overlap; grade II, no overlap, but no upward displacement; and grade III, with at least 1 cm of upward displacement of the distal clavicle (Fig. 2A, B).

Grade III implies that there are complete tears of the collateral ligaments of the joint, as well as a tear of the coracoclavicular ligament. In grade I injuries, it is customary to x-ray both sides on the same film (the other, normal, side for comparison) and to take a film with and without the patient carrying a 10-lb weight in each hand, which exaggerates any acromioclavicular separation that may be present.

The Sternoclavicular Joint and Proximal Clavicle

The sternoclavicular joint is rarely involved in trauma unless a direct blow is sustained. However, resorption of the sternoclavicular joint occurs in renal bone disease and osteolysis of the proximal clavicle as...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- 1. Trauma

- 2. Arthritis

- 3. Musculoskeletal Infection

- 4. Metabolic and Hematological Bone Disease

- 5. Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities

- 6. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors

- 7. Orthopaedic Hardware, Total Joint Replacements, and Their Complications

- 8. MRI and Ultrasound

- 9. Lumbar Spine

- Index