- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This best-selling book illustrates how schools can tell their own story. It draws on ground-breaking work with the National Union of Teachers to demonstrate a practical approach to identifying what makes a good school and the part that pupils, parents and teachers can play in school improvement. Its usefulness for and use by, classroom teachers to evaluate their practice will prove to be its greatest strength in an ever expanding effectiveness literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Schools Must Speak for Themselves by John MacBeath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WHY SCHOOLS MUST SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

Schools speak for themselves. They sometimes do so unconsciously, conveying implicit messages about their priorities and values. Some schools are able to speak for themselves with a high degree of self-awareness and self-assurance. They know their strengths and are secure enough to acknowledge their weaknesses.

It is an index of a nation’s educational health when its school communities have a high level of intelligence and know how to use the tools of self-evaluation and self-improvement. In healthy systems there is sharing and networking of good practice within and among schools on a collegial basis. It is an unhealthy system which relies on the constant routine attentions of an external body to police its schools.

Evaluating the role of the external inspection, Roger Frost HMI quotes Denis Healey’s autobiography: ‘What you do not know, indeed what you cannot know, is often more important than what you do know. The darkness does not destroy what it conceals.’1

Canadian researchers2 found that classroom observations by visiting auditors fail to touch the real day-today experiences of children and their teachers. In one school in our 1995 study students warned us to be wary of using impressions of visitors as a source of evidence. They said they had become very well trained on how to show the school off to its best for outsiders and inspectors. One student described the school as ‘a Jekyll and Hyde school with two faces. It has one face for visitors and one for us.’

There is an emerging consensus and body of wisdom about what a healthy system of school evaluation looks like. Its primary goal is to help schools to maintain and improve through critical self-reflection. It is concerned to equip teachers with the know-how to evaluate the quality of learning in their classrooms so that they do not have to rely on an external view, yet welcome such a perspective because it can enhance and strengthen good practice.

In such a system there is an important role for an Inspectorate or Office of Standards: to make itself as redundant as possible. It does so by seeking to reinforce the foundations of self-review and by helping schools to build more effectively on those foundations. HMI in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and OFSTED in England are charged with monitoring and reporting to ministers and the secretary of state on standards in the nation’s schools, but that is not their only, or even their primary, role. Their primary role is to help to raise standards, a goal that can be achieved first and foremost by helping schools to know themselves, do it for themselves and to give their own account of their achievements.

Who tells your story? This is the question put to schools by ex-HMI David Green in his work with Chicago schools.3 Is it the council or the local authority? Is it the test-makers and the assessment industry? Is it the politicians? Is it the local or national press? Is it Hollywood with its mythic classrooms (Blackboard Jungle, Dangerous Minds, Dead Poets Society, Mr Holland’s Opus)? David Green describes being met at the airport by an inspector whose licence plate bore the letters ‘I EVALUATE’. Often it is others who claim the right to speak on behalf of schools, to tell their stories for them, to amend and abridge and to add their own ending.

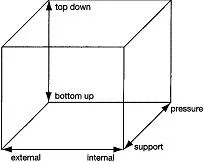

Diagram 1.1 Three dimensions of school evaluation and development

The ‘story’ is powerful because it is crucial to recognise that schools have a history, a unique cast of characters and a narrative that unfolds over time in unanticipated directions. That is how evaluation works— a continuing and continually revealing process. This is where school improvement takes root.

Diagram 1.1, adapted from school improvement work by Michael Schratz and his colleagues in Austria, describes three dimensions of school evaluation and development.4 The internal-external dimension represents a continuum from self-evaluation to evaluation from an outside source. Some systems could be depicted as lying at the extreme external end—that is, where the monitoring of quality and standards rests solely with an external inspectorate. In some systems there is no external body and quality assurance is exclusively the province of the school itself. Somewhere between is the point of balance of the two. Where this balance lies will differ from one country to another, and from one context to another but finding it is critical to the pursuit of quality and standards.

The pressure-support axis describes a continuum with, at one end, a high level of support from ‘the system’ and at the other extremity strong pressure. While this dimension is very real and highly significant, it is mainly in a subjective sense. That is, pressure and support are best understood in terms of what people experience, whether or not they feel that they are under pressure or whether they feel supported. Again there is a point of balance and it can only be found when there is a feedback loop which takes account of people’s individual and collective experiences. When that point of balance is achieved, people are enabled to do their job most effectively because they experience intrinsic satisfaction as well as extrinsic recognition and reward. The challenge to improve and to exceed their own expectations then comes primarily from within.

The top-down to bottom-up axis represents how a system sees and implements change. At one extreme it is delivered from above, by dictat, by legislation, by national structures. Alternatively, it can come entirely from below, from class teachers, from pupils and parents, building on day-to-day school and classroom practice. Most commentators agree that neither extreme is ideal and that the best kind of system is one in which bottom-up development is supported and endorsed from the top down.

This is a useful framework for thinking about how schools develop and improve. It is now widely accepted that this works best when there is the optimum blend of all three—support and pressure, bottom-up and top-down change, internal and external evaluation.5 Achieving the blend is the key factor in determining whether schools will grow and flourish or stagnate and decline. In the best of all possible

worlds the direction of change will be from pressure to support, from bottom up to top down and from internal to external evaluation. This optimum blend will, however, differ from area to area and school to school depending on history, context and culture and depending on each school’s state of psychological health.

SCHOOLS ARE DIFFERENT

We have seen schools in which self-evaluation could take root and flourish almost overnight. In those schools there was so much energy at teacher and pupil level that pressure and top-down direction would have been counter-productive. We also saw schools in which there was a pervasive cynicism, sometimes at the level of leadership, a climate which dragged teachers down and was damaging to students’ motivation and progress. We came across relatively high-achieving schools which were self-satisfied and complacent, limiting opportunities for teachers to grow professionally and inimical to the learning potential of young people. We worked with embattled schools with a reservoir of goodwill but without time, expertise or energy to turn things round. And most typical of all in our experience were the curate’s egg schools, good in parts, excellent in other parts, weak in some and with small dark corners into which light rarely seemed to penetrate.

During a recent self-evaluation workshop, a few departmental heads in a secondary school said that they would rather not know how well or badly they were doing either as teachers or as a department. One departmental head said that, as far as he was concerned, ignorance was bliss. ‘When ignorance is bliss it is folly to be wise’: so went the theme tune of a 1940s radio programme and it is a point of view easier to understand than to condemn. If you have done something badly, or less well than you had hoped, you might prefer not to look at the evaluations. You might wish to spare your ego further distress. As a long-term professional strategy, it is, however, clearly untenable.

So, the optimum balance has to be finely judged depending on the circumstances of the school. That is why the routine OFSTED or OHMCI cycle of inspections is inefficient and ill-informed. It treats schools as if their needs and skills were all the same. It proceeds from a single, simple model, essentially external and top down, the balance of pressure or support dependent on the qualities of any given inspection team.

Those of us who grew up in the fifties and sixties were weaned on a children’s literature of public schools,—Enid Blyton, St Trinian’s, Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Ronald Searle. In those fictions, which have, in all probability, shaped the images and values of generations, there were two separate realities—the world of the children and the world of classrooms and ‘skool’. There was an implicit assumption that what teachers taught in classrooms was what children learned, and that what went on in the underlife of the school could be put aside when you entered the classroom and got down to real lessons. Yet, with a curious ambivalence, there was also a view that it was on the playing fields and through the ethos of the school’s corporate life that character and leadership were forged, and proconsuls prepared for power.

Lindsay Anderson’s film If…was perhaps the first to bring into sharp juxtaposition the two realities of school life and to show that they were, in fact, intrinsically connected. In that film the informal pupil culture breaks through into the formal culture with devastating impact. The film Kes did the same work for the comprehensive school. It is, in its way, a classic piece of school evaluation, illuminating the connections between individual learning and school culture, between a bottom-up and top-down perspective on school life.

It was not until the 1970s or so that schools began to treat with serious concern issues of bullying, sexual harassment and racism. Ignorance had hitherto been bliss and it was in some places a matter of policy to turn a blind eye to what went on in the underlife of the school. It is, of course, still characteristic of many institutional cultures, most notably prisons.

Bullying has been exposed through schools’ willingness to self-evaluate. Equal opportunities policies have been given shape because the nature of the problem was recognised at a general level and in the specific context of the individual school. It is not school inspectors who can evaluate the extent of bullying in a school nor can they ‘inspect in’ a solution. It takes all the stakeholders in a school community to recognise and to deal with it. The same holds true for much of what is truly significant in the life of the school— psychological and physical safety, mutual respect, goodwill, motivation, morale, equity, relationships and communication.

Perhaps the most crucial indicator of school quality—how pupils learn—also tends to elude inspection. To know and understand learning requires the studied long-term insights and analysis of teachers and pupils reflecting together, using tools and finding the language to get inside the learning process. The external support and challenge comes from an increasingly rich body of literature on learning derived from painstaking long-term observation and analysis by researchers.

EVALUATION—WITH PURPOSE

Any attempt to evaluate a school or any other organisation is founded on values and purposes, covert or explicit. Over twenty years ago, based on his experience of evaluation in the American school system, Ernest House said:

Contrary to common belief, evaluation is not the ultimate arbiter, delivered from our objectivity and accepted as the final judgement. Evaluation is always derived from biased origins. When someone wants to defend something or to attack something, he often evaluates it. Evaluation is a motivated behaviour. Likewise, the way in which the results of an evaluation are accepted depends on whether they help or hinder the person receiving them. Evaluation is an integral part of the political processes of our society.6

THE POLITICAL PURPOSE

Ernest House reminds us that before we embark on discussion of more grandiose purposes we must be alert to political agendas, both on the large, international stage and in the micro-context of school and classroom. Evaluation is motivated behaviour. Its purpose is rarely without prejudice. It does not often set forth simply to ‘find out’ in a disinterested and speculative way. Evaluation usually comes with a mandate, a price, and with an audience in mind. The audience is crucially important because the language of evaluation has to persuade and convince, however balanced and fair-minded it strives to be.

OFSTED has been quick to recognise the importance of the audience. Which audience is Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector most keen to appeal to and why is it important? His primary audience is the public at large, and shaping that constituency is seen as crucial in winning hearts and minds and in securing the ideological high ground. If we have learned one thing in the lifetime of OFSTED, it is its highly political character.

But the same is also increasingly true of schools. Headteachers and teachers in the 1990s are much more likely to see themselves as operating in a political arena than they, or their predecessors, ever did before. The story told publicly about their schools through performance tables is one that they see as, at best, incomplete, at worst ‘a tale told by an idiot’. It is therefore incumbent on them to fill out or to retell the story. In modern parlance, it is called ‘putting a spin on it’ because political spinning is now openly acknowledged as a prerequisite of a free market.

While awareness of the political context of evaluation is crucial for schools and school leadership, it is not a guiding precept. Evaluation has other explicit purposes, often pursued in conjunction with one another. Herein lies the problem. If the purpose of evaluation is not clear and honest in respect of who it is for and who will benefit, it will be attended by confusion and mistrust.

THE ACCOUNTABILITY PURPOSE

One purpose for the story we tell about our schools is to satisfy parents and public that we are not reckless with the money which taxpayers have invested, nor reckless with the lives and futures of children. The story is an ‘account’ and accountability has a noble purpose. To protect the interests of individuals and of democracy is an inherent requirement of public institutions and a defining characteristic of ‘professionalism’.

Accountability has always been implicit and sometimes painfully explicit, as in the system of payment by results of the last century. The 1980s did, however, mark a modern watershed in the place and purpose of accountability. Under the Thatcher regime, the idea of a ‘market’ in education was born, and the market mechanism was to measure inputs and outputs. Appropriating the language of commerce, its purpose was to evaluate returns on public investment. Auditing was born and school accounts were no longer stories told by people but figures and tables produced by statisticians and bookkeepers. John Gray and Brian Wilcox have t...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1. WHY SCHOOLS MUST SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

- 2. HUNT THE UNICORN: THE SEARCH FOR THE EFFECTIVE SCHOOL

- 3. HOW THE FRAMEWORK WAS DEVELOPED: THE 1995 STUDY

- 4. EXPLORING THE THEMES

- 5. THE GOOD TEACHER

- 6. INSPECTION PRIORITIES: ARE THEY YOURS?

- 7. WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

- 8. WHAT HAPPENS IN OTHER COUNTRIES?

- 9. A FRAMEWORK FOR SELF-EVALUATION

- 10. MAKING IT WORK IN YOUR SCHOOL

- 11. USING THE FRAMEWORK

- 12. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- NOTES